ARTS

Exhibitions

Whims ancient and modern

Giles Auty

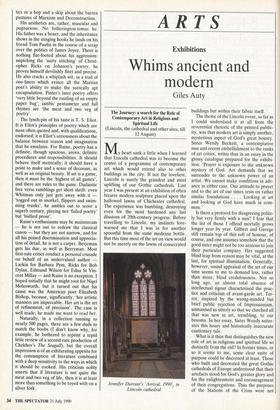

The Journey: a search for the Role of Contemporary Art in Religious and Spiritual Life (Lincoln, the cathedral and other sites, till 12 August)

My heart sank a little when I learned that Lincoln cathedral was to become the centre of a programme of contemporary art which would extend also to other buildings in the city. If not the loveliest, Lincoln is surely the grandest and most uplifting of our Gothic cathedrals. Last year I was present at an exhibition of often bizarre modern sculpture placed upon the hallowed lawns of Chichester cathedral. The experience was humbling, destroying even for the most hardened any last illusions of 20th-century progress. Before travelling to Lincoln, my instincts fore- warned me that I was in for another spoonful from the same medicine bottle. But this time most of the art on view would not be merely on the lawns of consecrated buildings but within their fabric itself.

The theme of the Lincoln event, so far as I could understand it at all from the reverential rhetoric of the printed public- ity, was that modern art is simply another, mysterious aspect of God's great bounty. Sister Wendy Beckett, a contemplative nun and recent embellishment to the ranks of art critics, writes thus in an essay in the glossy catalogue prepared for the exhibi- tion: 'Prayer is exposure to the unknown mystery of God. Art demands that we surrender to the unknown power of an artist. We cannot make conditions in adv- ance in either case. Our attitude to prayer and to the art of our times rests on rather similar foundations . . . . Looking at art and looking at God have much in com- mon.'

Is there a protocol for disagreeing polite- ly but very firmly with a nun? I fear that the list of those I offend mortally grows longer year by year. Gilbert and George still remain top of this roll of honour, of course, and one assumes somehow that the good sister might not be too anxious to join their particular company. Her suggested blind leap from reason may be vital, at the last, for spiritual illumination. Generally, however, sound appraisal of the art of our time seems to me to demand less, rather than more, blind credulousness. Not so long ago, an almost total absence of intellectual rigour characterised the prac- tice and criticism of avant-garde art. Ter- ror, inspired by the wrong-minded but brief public rejection of Impressionism, unmanned us utterly so that we clutched all that was new in art, trembling, to our bosoms. In her essay, Sister Wendy reiter- ates this hoary and historically inaccurate cautionary tale.

What is it then that distinguishes the new role of art in religious and spiritual life so distinctly from the old? In former times, or so it seems to me, some clear unity of purpose could be discerned at least. Those who built and decorated the great Gothic cathedrals of Europe understood that their artefacts stood for God's greater glory and for the enlightenment and encouragement of their congregations. Thus the purposes of the Stations of the Cross were not merely vague adjurations to save old news- papers or even the trees of the rainforest but rather to contemplate the manner in which humankind had treated its intended saviour. Even modern artists of rare idiosyncrasy from pre-war times, such as Eric Gill, harnessed their considerable talents within the framework of accepted Christian iconography; those who have never done so should make an effort to see Gill's Stations of the Cross in Westminster cathedral. However, what is happening at Lincoln is a major depature from such traditions. For a start, artists who have been invited to take part in the Lincoln event may have had little interest in or agreement with Christian principles and thus 'do their thing' largely in response to the ambience of ecclesiastical buildings.

Who, by any stretch of the imagination, might be said to benefit from all of this?

The exhibition brochure is clear, for once, on the possible beneficiaries: 'Each age has a responsibility to find new ways of ex- pressing faith and reaching people who feel excluded and distanced in their religious life.' Are we approaching here that absurd and divisive ground whereon claims are made that many more teenagers would attend church if only priests could be persuaded to wear rock-and-roll tee-shirts rather than those absurd chasubles? Yet for each such hypothetical teenager there is probably a score of flesh-and-blood Christ- ians who have been saddened unutterably by attempted updatings of their liturgy.

For Catholics the replacement of their everyday Latin Mass with a grisly vernacu- lar version provides merely one example.

Visitors to Lincoln cathedral will cur- rently encounter two large abstract paint- ings by Jennifer Durrant, hung below windows in the north and south aisles. By colour and design both would make wonderful patterns for ultra-modern rugs, yet neither could really be said to offer any obvious hope to the ecclesiastically disen- chanted. Hard by these, a series of five expensive-looking copper panels bear identical minimal motifs in black and white. But is their message to the spiritual- ly distanced similarly clear-cut? By con- trast, the large slate circle contributed by Richard Long and an alternative altar by Richard Devereux seem to look back, with a certain nostalgia, to pre-Christian times.

Are we being asked to mourn the passing of the Druids — noted persecutors of early Christians — or merely the demise of a 'healthier', ancient pantheism? Apparently the gold leaf which is all that covers Leonard McComb's 'Portrait of a Young Man Standing' was at least one leaf too few for the sensibilities of one of Lincoln's deans. Probably other exhibits caused less embarrassment merely because merit and meaning were less approachable.

The ruins of the Bishop's Palace contain, among other things, aesthetically pleasing but purely organic sculpture by Peter Randall-Page, attractive nods in the direc- tion of Eastern faiths in the prayer sticks of Eileen Lawrence plus a vast, wax-covered floor, brainchild of Glen Onwin, who hopes that moulds and crystals may flour- ish therein. Is this a metaphor for Christian growth and renewal? Or for rot and decay? To Christians who are still oppressed bru- tally for their faith in other lands, the agonised goofiness of the Anglican church must sometimes take some crediting.

Previous page

Previous page