ARTS

Architecture

Designs for survival

Alan Powers

Barcelona (Architectural Association, till 3 April)

Can Our Cities Survive? was the title of a 1942 book edited by the Barcelona archi- tect Jose Luis Sert, then an exile in Ameri- ca. Sert returned to his native city to build the Fundacio Miro, a museum for the work of the Catalan surrealist, which opened in 1975, the year of Franco's death and the symbolic date for the beginning of the city's regeneration.

The exhibition Barcelona at the Architec- tural Association (34-36 Bedford Square, WC1) shows the work of four architects (one of them strictly speaking a designer) who have contributed to make this city a focus of attention as its long build-up to the Olympics comes to fruition, with new buildings, urban quarters, airport terminal and, perhaps most important of all, new roads and other more invisible infrastruc- tural improvements like drains.

With its mediaeval quarter, its long, leafy Ramblas lined with stalls selling caged birds and potted palms, and its architec- Interior of the Torres d'Avila bar, Barcelona tural masterpieces from the Art Nouveau period by Antonio Gaudi and others, Barcelona appears as a city which has made the transition from the picturesque underdevelopment of the early 1970s to chic modernity in a relatively painless way, at least for those not contributing to the local taxes.

Some of the work on show, such as the new archery stadium by Enric Miralles, resembles the disjointed, highly theoretical architecture popular among tutors and stu- dents at the AA for the last ten years, but in its realisation, dug into a hillside, with brilliant sunlight entering small, pierced, triangular holes in a concrete wall to shine on bright-blue-tiled washrooms, it has an undeniable element a pure pleasure, enhanced by the relationship to the land- scape, 'affirmative, even restorative vis-i- vis nature', as the American critic William Curtis has described the work.

Pleasure and enjoyment are the aim of the bars and restaurants which have come to represent Barcelona's cultural cutting edge. Fortunate the city so scaled to sup- port an intelligentsia alive to design values but not so large as to be overwhelmed by anonymity. The Tragaluz restaurant by the designer Pepe Cortes is full of the slightly fantastic and irrational stunts that made modern architecture in its 1930s heyday, even in London, something to associate with entertainment and imagination. The spiral staircase to the upper level is built into a tree trunk. The furniture is specially made, because the right kind of small workshop still exists in the city to make it at a reasonable price, partly as a legacy of the high import taxes on foreign furniture in the past.

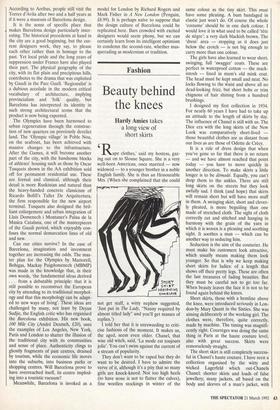

A more ambitious bar is the Torres d'Avila by Alfredo Arribas and the design- er Javier Mariscal, constructed within a reproduction mediaeval gateway at the Poble Espanyol, the stage-set traditional village built on the slopes of Montjuic for the 1929 international exhibition. The two towers symbolise the sun and moon, mas- culine and feminine respectively, a simple enough concept but one carried out with great originality and fanatical attention to detail. Imagine a similar construction going up on the South Bank — one whose func- tion is primarily to be a work of art. According to Arribas, people still visit the Torres d'Avila after two and a half years as if it were a museum of Barcelona design.

It is the sense of specific place that makes Barcelona design particularly inter- esting. The historical precedents at hand in the city are a good beginning, but the cur- rent designers work, they say, to please each other rather than in homage to the past. Yet local pride and the long years of suppression under Franco have also played their part. The physical geography of the city, with its flat plain and precipitous hills, contributes to the drama that was exploited by Gaudi in the Parc Guell. 'Regionalist' is a dubious accolade in the modern critical vocabulary of architecture, implying provincialism and 'folk' quality, but Barcelona has interpreted its identity in such strong architectural terms that the product is now being exported.

The Olympics have been harnessed to urban regeneration through the construc- tion of new quarters on previously derelict land. The 'Olympic village' in Poble Nou, on the seafront, has been achieved with massive changes to the infrastructure.

After the Games, it will become another part of the city, with the handsome blocks of athletes' housing such as those by Oscar Tusquets shown in the AA exhibition sold off for permanent residential use. These are formal and classical, although their detail is more Ruskinian and natural than the heavy-handed concrete classicism of Ricardo Bofill's Taller De Arquitectura, the firm responsible for the new airport terminal. Tusquets also designed the bril- liant enlargement and urban integration of Lluis Domenech i Montaner's Palau de la Musica Catalana, one of the masterpieces of the Gaudi period, which enjoyably con- fuses the normal demarcation lines of old and new.

Can our cities survive? In the case of Barcelona, imagination and investment together are increasing the odds. The mas- ter plan for the Olympics by Martorell, Bohigas, Mackay Puigdomenech (MBMP) was made in the knowledge that, in their own words, 'the fundamental ideas derived . . . from a debatable principle: that it is still possible to reconstruct the European city by attending to its traditional morphol- ogy and that this morphology can be adapt- ed to new ways of living'. These ideas are challenged by many, not least by Deyan Sudjic, the English critic who has organised the Barcelona exhibition. His new book, 100 Mile City (Andre Deutsch, £20), uses the examples of Los Angeles, New York, Paris and London to shatter the illusion of the traditional city with its communities and sense of place. Authenticity clings to ghostly fragments of past centres, drained by tourism, while the economic life moves into the suburbs, into business parks or shopping centres. Will Barcelona prove to have overreached itself, its centre implod- ing into a touristic vacuum?

Meanwhile, Barcelona is invoked as a model for London by Richard Rogers and Mark Fisher in A New London (Penguin, £8.99). It is perhaps naive to suppose that the design culture of Barcelona could be replicated here. Bars crowded with excited designers would seem phony, but we can certainly learn from its intelligent optimism to condemn the second-rate, whether mas- querading as modernism or tradition.

Previous page

Previous page