A BETTER ISM FOR OUR TIME

A.N. Wilson advocates something more suited to us than socialism, conservatism or libertarianism (certainly not Blairism) IN an elegant essay recently, Matthew Par- ris meditated upon the concept of liberty which was so dear to certain members of his own political party, the Conservatives. In a paper entitled 'Tolerance', which he read to the Conservative Philosophy Group and then published, in truncated form, in the Times, he argued for a devel- opment and a cherishing of the concept of privacy — one which was perhaps difficult to define on the statute books, but which was very easy to recognise when politicians tried to invade it.

Parris is an attractive thinker, but it seems to me that there are insuperable dif- ficulties about trying to pursue the con- cepts of liberty, and that of privacy with which it is interwoven, without embracing a gentle, happy type of anarchism. And it is, I would think, to the anarchists, and not to the Liberals or the Conservatives that we should be looking for guidance at the present time. Tolstoy or Thoreau have more to tell us than Jeremy Bentham or Bagehot.

My reason for saying this is that even to use the word 'liberty' within the existing political framework is to suggest that one group in society — the governing class, or the elected politicians, or the churches has a recognisable right to boss any other group. And this is plainly not the case. The only power is money. No political system has ever been able to overcome it Marxism least of all. The results of trying to abolish money and its power are worse than anything which even Murdoch or Soros could do. The only sensible course is to cultivate our gardens and withhold sup- port from any political group or any politi- cal thought whatsoever. In short, to be sort of anarchists.

It is a commonplace of the libertarian Right that excellent education and hospitals were available throughout the civilised world before there was a single 'state' school or State Registered Nurse. This 'lib- ertarian' train of thinking led, in the Thatch- er years, to a series of changes in life, some major, some minor, which were represented at the time as extensions of personal liberty: privatisation, the shareholders' democracy, the sale of council houses and the extension of the property-owning class. The idea seemed to be that we did not need state road-sweepers, state prisons, state dinner ladies. Everything would be let out to pri- vate tender and the state would somehow get off 'our' backs. The 'burden' of tax would be lifted. We would all be freer. The watchword was liberty.

The doctrinal objection to this sort of economic liberalism is that capitalism is too voracious and Darwinian a force to be allowed free rein. It destroys as well as builds up. Some measure of 'state interfer- ence' — it was argued by the old soft Left, the Tory Wets and others — is needed to hold the beast in check. Otherwise you end up with Cardboard City and an under- class.

Well, the Eighties came and went. Most of us felt neither more nor less `free' than we did before Thatcher. A few council-flat dwellers were happy to 'own' their own homes. A rather larger number got caught in negative equity and pined for the good old days of the rent man. The original Thatcherite dream — that we would reduce taxation, reduce public spending, roll back the frontiers of the state — has faded as dreams do. We all pay more tax, when indirect and direct are added together, than we did in pre- Thatcher days. The underclass, as it is distastefully called, has grown larger and poorer. The rest of us, far from being freer or richer, found that we had entered an unwanted contract.

The decent apolitical majority (as opposed to the monetarist militant ten- dency) continued to want 'the state' to help those who, it was supposed, could not be helped in any other way. And in order to provide this help we were prepared to deliver the power to administer it into the hands of politicians we disliked and despised. The longer our shopping list, the happier the politicians (of all hues and persuasions) became. In spite of all our protestations during the Thatcher years that we disliked 'state interference', we had actually persuaded ourselves that, without politicians, we could not have any of the things which we needed to maintain a civilised life: unemployment pay, disabil- ity allowances, false teeth and spectacles for old-age pensioners, primary schools, roads, farm subsidies, artificial limbs, stu- dent grants, policemen, the armed forces, a royal yacht, the Bodleian library, more and better nurses, cleaner streets, etc.

In countries, or even in parts of our own country, where there are still true political issues to be settled, such as who lives on which bit of land, the climate of debate is completely different. Compare Northern Ireland with the mainland. Why do Paisley, Adams, Trimble and the rest, whatever we think of them, seem like creatures who have come to us from another age? It is because they, unlike any English politicians of influence, actually represent a con- stituency, a set of followers, a point of view. Vote Adams into power and you get some- thing very different from what you would get if you voted Paisley into power. We all know, by contrast, that the English political parties have more or less identical 'policies' and more or less identical nonentities (in terms of world political history) in charge of them. We don't need or want Men of Destiny. Instead, we need, or feel we need, politicians who will deal with our shopping list of requirements.

In the middle of this list — schools, pen- sions, hospitals, the RAF and so forth we have chosen at the moment to identify one problem area: welfare. Some people speak of welfare dependency as if it were a disease afflicting the lumpenproletariat. The rest of us, it is assumed, have no such problems as lone mums or the unemploy- able black-teenage-mugging class. While deploring the habits of 'dependency' built up by these young fellow citizens, who probably each cost every taxpayer a few hundred pounds each week, we continue to expect politicians to spend thousands of pounds a week on our behalf, paying for our army, our police, our artificial hip replacements, etc. Politicians, especially the New Labour variety, earn momentary applause by promising to 'get tough', and this means cutting out tiny items from the shopping list such as the royal yacht or stu- dent grants.

But of course it means that the contract remains. The politicians depend on our believing that they alone can prevent what they would call anarchy — foreign invasion, or an assault by criminals on the propertied classes, or the starvation of the very poor. As soon as we stopped believing this, we should no longer need the politicians and they would no longer have all the pow- ers to boss us, which is their drug.

Libertarians of the Right like to com- plain about the Nanny State, the hateful alliance of politicians, policemen, doctors and other professional busybodies who interfere with our decision to smoke a cigarette, eat a T-bone steak, drink and drive. The political system ensures that the true libertarians in the Conservative party (and there are a few, a very few) have to share a platform with economic liberals who are the reverse of libertarian when it comes to some area of life of which they happen to disapprove — homosexuality, for example. The truth is that the true libertarian must have the courage to embrace anar- chism tout court. Once you have seen that the whole economic and political structure of our society as at present constituted is based on a gigantic con-trick which we are playing on ourselves, then anarchism and not 'libertarianism' becomes the natural thing for you to believe. Politicians and those who support the present status quo have a vested interest in our believing that they are the cure for those ills of which they are the manifest cause. The most obvious example of this is the police. Thatcher was a classic example of the economic liberal who was the reverse of a libertarian in practical politics. She spent more and more public money each year increasing the size of the police force, giving them bigger and more expen- sive helicopters, more surveillance equip- ment and greater power to interfere in our lives. The result has been an increase in all known crimes without parallel in our histo- ry. If burglaries and crimes against proper- ty have very slightly declined in recent years, that is the result of so many of us buying burglar alarms; it has nothing to do with the police. Many of them are corrupt and encourage criminal rings of which they are themselves members. But that is not the point. The very existence of the police causes crime, just as the existence of pris- ons causes criminals, and the existence of motorways increases rather than diminish- es traffic.

The recent fracas between Saddam Hus- sein and the Americans reminds us of the truly wicked absurdity of 'our' pretending that we had a quarrel with the people of Iraq, a quarrel which 'we' were proposing to 'solve' by sending young servicemen and servicewomen to die in horrible circum- stances, or forcing them to inflict dreadful harm on the citizens of Baghdad on 'our' behalf.

Yet these are the sort of powers which we give to headstrong puppies like Blair and Clinton in exchange for thinking that we could not feed our hungry neighbours, look after our sick, educate our children, house our oldies, keep down our foxes, protect our private possessions, without the assistance of the politicians.

The European 'experiment' has been, from an anarchist point of view, a useful object-lesson. On the one hand, 'Europe' has been, in the eyes of the sceptics, a superstate in embryo, an Orwellian face- less power interfering in our lives, demanding that we don't smoke cigarettes of a certain strength, that we pasteurise and thereby ruin good French or English cheeses, and so on and so forth. No doubt the Brussels bureaucracy does have this tendency, but its enemies do themselves no service by reminding us that the Euroc- racy is 'unelected'. For this in turn reminds us that the boring business of `government' goes on, facelessly and Gogolishly, whether we elect politicians to do it or not. Yes, the Eurocrats have changed life, but only in a host of trivial ways that elected politicians would have done anyway. The great thing about the Eurocracy, as Auberon Waugh never tires of reminding us, is that they have rendered all national governments impotent. If our hideously self-important 'sovereign parlia- ment' has been neutered by what Waugh calls the Belgian ticket-inspectors, let's all cheer.

Let us concentrate on the extent to which power, far from being transferred from the sovereign parliaments to one centralised European base, has in fact been dissipated. There is no Napoleon, no Wizard of Oz operating the European controls. While one might hate and despise all its regula- tions, and all its silly enthusiasts from Jacques Delors to Roy Jenkins, we can at least be glad for the damage Europe has done — irreparable damage, we hope — to national government.

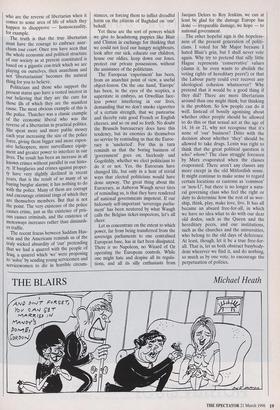

The other hopeful sign is the hopeless- ness of the present generation of politi- cians. I voted for Mr Major because hated Blair's grin, but I shall never vote again. Why try to pretend that silly little Hague represents 'conservative' values (damn it, he even wants to abolish the voting rights of hereditary peers!) or that the Labour party could ever recover any ideological cohesion whatsoever? Why pretend that it would be a good thing if they did? There are more libertarians around than one might think; but thinking is the problem. So few people can do it well. Instead of bossily agonising about whether other people should be allowed to do this or that sexual act at the age of 14, 16 or 21, why not recognise that it's none of 'our' business? Ditto with the decision about whether 'they' should be allowed to take drugs. Lenin was right to think that the great political question is who? whom? The class struggle foreseen by Marx evaporated when the classes evaporated. There aren't any classes any more except in the old Mitfordish sense. It might continue to make sense to regard certain locutions or customs as 'common' or 'non-U', but there is no longer a natu- ral governing class who feel the right or duty to determine how the rest of us wor- ship, think, play, make love, live. It has all became an absurd free-for-all, in which we have no idea what to do with our dear old dodos, such as the Queen and the hereditary peers, and our institutions, such as the churches and the universities, who belong to the old days of deference. At least, though, let it be a true free-for- all. That is, let us both obstruct busybody- dom wherever we find it, and do nothing, so much as by one vote, to encourage the perpetuation of politics.

Previous page

Previous page