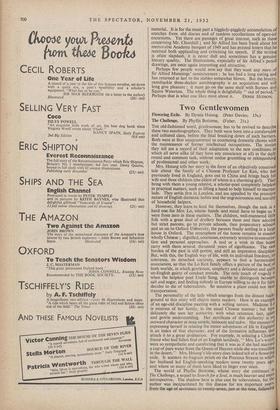

Two Gentlewomen

THE old-fashioned word, gentlewoman, has to be revived to describe these two autobiographers. They both were born into a comfortable and cultured class, before the final breaking down of such barriers. Both were at first unaccustomed to combining domestic chores with the maintenance of former intellectual occupations. The stories they tell are a record of their adaptation to the new conditions in which all serve alike (if they have any conscience at all) in the daily round and common task, without undue grumbling or relinquishing of professional and other work.

Mrs. Hsiung tells her story in the form of an objectively conceived tale about the family of a Chinese Professor Lo Ken, who has previously lived in England, goes out to China and brings back his wife and three children (the eldest of whom is a charming girl). They bring with them a young relative, a scholar-poet completely helpless in practical matters, such as lifting a hand to help himself to marina. lade. They settle first, in London, and are appalled by the primitive nature of English domestic habits and the ungraciousness and scarcity of household helpers.

However, they learn to fend for themselves, though the task is 3 hard one for Mrs. Lo, whose hands and mind have to begin as it were from zero in these matters. The children, well-mannered little folk with a great deal of drollery between them and their adoring but strict parents, go to private schools, then preparatory schools and so on to Oxford University, the parents finally settling in a large house in Oxford. The atmosphere of the home remains in essence wholly Chinese ; dignified, courteous, extremely tentative in converse' tion and personal approaches. A nod or a wink in that home carry with them several thousand years of significance. The vast burden of the past is still potent, and still an impressive discipline' But, with this, the English way of life, with its individual freedom, its tolerance, its detached curiosity, appears to find a harmonious, association, so that the Lo Ken family offers a picture of the best of both worlds, in which gentleness, simplicity and a delicious and quire un-English gaiety of conduct preside. The only touch of tragedy i5 when the helpless poet Uncle Sung, unable to distinguish between salt and sugar, and finding nobody in Europe willing to do it for hint decides to die of tuberculosis. So sensitive a plant could not bear transportation. The personality of the lady which emerges from the distant back' ground to this story will charm many readers. Here is an example of an age-old discipline meeting with a willing nature. Madame I-0 is mistress of her family, in the usual Chinese manner ; but hog' delicately she uses her authority, with what reticence, tact, quiet and gentle understanding. Her certificate of this authority • is ail outward character at once simple, innocent and naive. Her manner 01 expressing herself in relating the minor adventures of life in England is an index of that character, and of the formative influences that attach it to a great civilisation. For example, in solacing a Chinese friend who had fallen foul of an English landlady, " Mrs. Lo's words, were so sympathetic and comforting that it was as if she had received a cup of pure water from the Queen of Heaven while she was travelling in the desert." Mrs. Hsiung's life-story does indeed tell of a flowering exile. It scatters its fragrant petals on the Precious Stream to which her husband led English-speaking readers some twenty years ago and where so many of them have liked to linger ever since. The world of Phyllis Bottome, whose story she continues in The Challenge, a sequel to Search for a Soul, is much heavier and mod introspective. The shadow here is also cast by tuberculosis, for the author was incapacitated . by this disease for ten important years,: from the age of seventeen to twenty-seven, just at,the following her beloved sister's death from the same sickness; When she should have been going out to taste life to the full. The story' is one that dates heavily, especially otrthe economic and religioui aspects: She tells of staying in Tunbridge Wells with her grandparents, whose household was overshadowed by poverty, their income having been reduced, through rash speculation, from fifteen thousand to`three thousand a year. The author's illtAss turned her mind more to the problem of self-development than to romantic love. She frankly says that the years after adolescence are dominated not by love but by the struggle for self-discovery and the assertion of personal aims. That belief colours the book, and the reader is not surprised when the story comes to a goal with the acceptance of the teachings of Adler, the advocate of Personal Psychology.

RICHARD CHURCH.

Previous page

Previous page