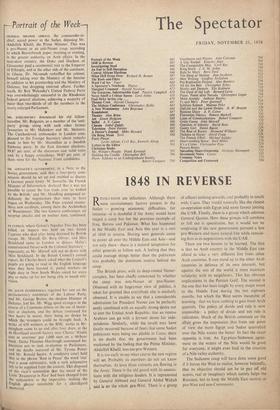

1848 IN REVERSE

REVOLUTIONS are infectious. Although there „were revolutionary factors present in the Sudan — growing economic difficulties, for instance—it is doubtful if the Army would have staged a coup but for the previous example of Iraq, Burma and Pakistan. What has happened in the Middle East and Asia this year is a sort of 1848 in reverse. Having seen generals come to power all over the Middle East and Asia—and not only there—there is a natural temptation for other generals to follow suit. A feeling that they could manage things better than the politicians was probably the dominant motive behind the coup.

The British press, with its deep-rooted Nasser- complex, has been chiefly concerned by whether the coup was anti-Nasser or pro-Nasser. Obsessed with its bogeyman view of politics, it takes for granted that everybody else is similarly obsessed. It is unable to see that a considerable admiration for President Nasser can be perfectly easily combined with an equally strong desire not to join the United Arab Republic, that an intense Arabism can go with a fervent desire for inde- pendence. Similarly, while the revolt may have finally occurred because of fears that some Sudan politicians were being too pliable in Cairo, there is no doubt that the government had been weakened by the feeling that the Prime Minister, Abdullah Khalil, was too pro-Western.

It is too early to say what course the new regime will set. Probably its members do not yet know themselves. At least three currents are flowing in the Army. There is the old guard with its associa- tions with the religious leaders. It is represented by General Abboud and General Abdul Wahab and is on the whole pro-West. There is a group of officers looking towards, and probably in touch with, Cairo. They would naturally like the closest co-operation with Egypt and some favour joining the UAR. Finally, there is a group which admires General Qassim. How these groups will combine or fall out is speculation, but it would not be surprising if the new government pursued a less pro-Western and more neutral line while remain- ing firm in its negotiations with the UAR.

There are two lessons to be learned. The first is that no Arab country in the Middle East can afford to take a very different line from other Arab countries. It can stand up to the other Arab countries in defence of its own interests, but against the rest of the world it must maintain solidarity with its neighbours. This has obvious implications in the Persian Gulf. The second is the one that has been taught by every major event in the Middle East during the last eighteen months, but which the West seems incapable of learning : that we have nothing to gain from Arab quarrels. The policy of divide and rule is now impossible: a policy of divide and not rule is ridiculous. Much of the British comment on the affair gives the impression that from our point of view the more Egypt and Sudan quarrelled over the Nile waters the better. In fact the exact opposite is true. An Egyptian-Sudanese agree- ment on the waters of the Nile would be good for everyone; it might even lead to the creation of a Nile valley authority.

The Sudanese coup will have done some good if it forces the West to realise, however belatedly, that its objective should not be to pay off old scores, real or imaginary which merely helps the Russians, but to keep the Middle East neutral or pro-West and non-Communist.

Previous page

Previous page