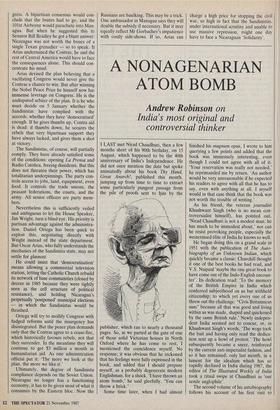

MORE PROS FOR THE CONTRAS

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard sees the

Nicaraguan opposition emerging as a force to reckon with

Washington THE Ortega brothers were reviled as `putschist adventurers' by the Sandinista front when they made a tactical alliance with the bourgeoisie before the Nicaraguan revolution in 1979. But history bore them out. They went on to mastermind the insurrection, then purge the useful idiots. In the tradition of Lenin they are consum- mate opportunists. Hence Daniel Ortega's latest volte-face: a ceasefire, and negotia- tions with the Contras through the media- tion of his arch-enemy Cardinal Obando y Bravo.

Conservatives here are sickened. They see compromise and defeat at every turn: on taxes, on the Supreme Court, on arms control, and now on the Contras. But nothing is ever settled once and for all in Washington, particularly the debate over Nicaragua. Congress has gone to the brink many times. In 1984 it cut Contra aid altogether. Yet in the end `low intensity conflict' with proxy forces has proved a safer option for politicians than accepting another Cuba and risking the danger of contagion in sickly El Salvador. Nor is Contra aid necessarily a casualty of Reagan's lost clout in Congress. The American liberal establishment is under- going a change in its view of the Nicara- guan civil war. Two weeks ago the Contras received certificates of guerrilla proficiency on the front pages of the Washington Post and the New York Times. We read that the rebels are disciplined, committed, popular, and that they dominate territory. We also read not only that the Sandinistas intimi- date systematically but also that the mili- tias and security forces in effect operate as death squads. This is a new theme in the American press, though not in Nicaragua. The Human Rights Commission has stacks of testimonies from the first days of Sandi- nismo, some of which I have investigated and found accurate. 'Why has it taken so long,' its director, Lino Hernandez, asked me sadly last year. 'Why didn't you believe us then?'

The Sandinistas are losing the benefit of the doubt. The Contras are slowly winning it. The best thing that ever happened to them was the Iran-Contra scandal. It was 'el private supply network' (as it is known in Spanish) of Oliver North and General Secord that so hindered the evolution of an authentic insurgency. North had little time for the intellectuals, the liberals, the ex- Sandinistas in the Contra southern front. He channelled the secret funds to Adolfo Calero, the crusty conservative whose lieutenants are most closely linked to the ancien regime. Arturo Cruz, the former Sandinista ambassador to Washington and then the most favoured Contra leader, was shunted aside, used only as a salesman in Congress.

011ie North's cabals and conspiracies seem like another world now. 'Everything has changed,' says a Democratic congres- sional aide. 'The Somocistas don't count any more.' A smooth new organisation has been created called the Nicaraguan resist- ance. The directorate allocates American military aid, and the liberals control four of the six seats. Among them is Alfredo Cesar, the former Sandinista chairman of the Central Bank. He says he is glad that zealots in the Reagan administration are no longer pushing his cause, poisoning the wells in Congress. 'Over the last nine months we've become a lobbying organisa- tion. Now we're doing our own work. . . our relationship with the United States is a lot more like a real alliance.'

The debate is softening in Washington. Moral outrage over Contra aid is in- creasingly confined to irrelevant sects on the Left. They turned out last week to welcome Daniel Ortega for prayers at a Presbyterian church. Among them were the Massachusetts Buddhists whose lugub- rious chant went on for so long that I began to feel sorry for Ortega, not just because his American constituency was reduced to this, but because the event was so painfully embarrassing.

It is now the instinctive isolationism of the American people, not moral qualms, that handicaps the Contras. President Oscar Arias of Costa Rica underrated this isolationism. He calculated that if the Sandinistas, whom he loathes, did not comply with the conditions of his peace plan, they would be exposed and discre- dited. This would at last galvanise Con- gress. A bipartisan consensus would con- clude that the brutes had to go, and the 101st Airborne would parachute into Man- agua. But when he suggested this to Senator Bill Bradley he got a blunt answer: Nicaragua was not worth the bones of a single Texan grenadier — so to speak. It Arias undermined the Contras, he and the rest of Central America would have to face the consequences alone. This should con- centrate his mind.

Arias devised the plan believing that a vacillating Congress would never give the Contras a chance to win. But after winning the Nobel Peace Prize he himself now has immense leverage on Congress. He is the undisputed arbiter of the plan. It is he who must decide on 5 January whether the Sandinistas have complied with the accords, whether they have `democratised' enough. If he gives thumbs up, Contra aid is dead: if thumbs down, he secures the rebels that very bipartisan support they have always lacked, and gives them a shot at victory.

The Sandinistas, of course, will partially comply. They have already satisfied some of the conditions: opening La Prensa and Radio Catolica, freeing dissidents. But this does not threaten their power, which has totalitarian underpinnings. The party con- trols access to jobs, land, equipment, even food. It controls the trade unions, the peasant federations, the courts, and the army. All senior officers are party mem- bers.

Nevertheless this is Sufficiently veiled and ambiguous to let the House Speaker, Jim Wright, turn a blind eye. His priority is partisan advantage against the administra- tion. Daniel Ortega has been quick to exploit this, negotiating directly with Wright instead of the state department. But Oscar Arias, who fully understands the mechanics of the Sandinista state, may not settle for glasnost.

He could insist that 'democratisation' means allowing a commercial television station, letting the Catholic Church rebuild its network of base communities (closed by decree in 1985 because they were rightly seen as the cell structure of political resistance), and holding Nicaragua's perpetually `postponed' municipal elections — in which the Sandinistas would be thrashed.

Ortega will try to mollify Congress with fudged reforms until the insurgency has disintegrated. But the peace plan demands only that the Contras agree to a cease-fire, which historically favours rebels, not that they surrender. In the meantime they will continue to get $3 million a month in humanitarian aid. As one administration official put it: 'The more we look at the plan, the more we like it.'

Ultimately, the degree of Sandinista compliance depends on the Soviet Union.

Nicaragua no longer has a functioning economy, it has to be given most of what it consumes by the Eastern bloc. Now the Russians are baulking. This may be a trick. One ambassador in Managua says they will double the subsidy if necessary. But it may equally reflect Mr Gorbachev's impatience with costly side-shows. If so, Arias can charge a high price for stopping the civil war, so high in fact that the Sandinistas, under international scrutiny and unable to use massive repression, might one day have to face a Nicaraguan 'Solidarity'.

Previous page

Previous page