BOOKS

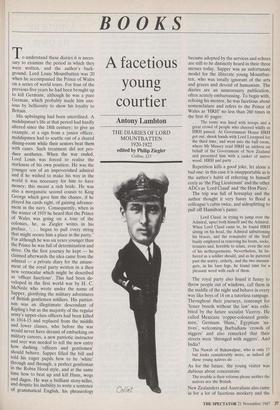

A facetious young courtier

Antony Lambton

THE DIARIES OF LORD MOUNTBA'FTEN 1920-1922 edited by Philip Ziegler

Collins, £15

To understand these diaries it is neces- sary to examine the period in which they were written, and the author's back- ground. Lord Louis Mountbatten was 20 when he accompanied the Prince of Wales on a series of world tours. For four of the previous five years he had been brought up to kill Germans, although he was a pure German, which probably made him anx- ious by bellicosity to show his loyalty to Britain.

His upbringing had been uncivilised. A midshipman's life at that period had hardly altered since the 18th century; to give an example, at a sign from a junior officer, midshipmen had to scuttle out of a shared dining-room while their seniors beat them with canes. Such treatment did not pro- duce aesthetes. When the war ended, Lord Louis was forced to realise the starkness of his own position. He was the younger son of an impoverished admiral and if he wished to make his way in the world it was necessary for him to have money; this meant a rich bride. He was also a morganatic second cousin to King George which gave him the chance, if he played his cards right, of gaining advance- ment in the navy. Consequently, when in the winter of 1919 he heard that the Prince of Wales was going on a tour of the colonies, he, as Ziegler writes in his preface, `. . . began to pull every string that might secure him a place in the party.' For although he was six years younger than the Prince he was full of determination and drive. On the first journey he kept — he claimed afterwards the idea came from the admiral — a private diary for the amuse- ment of the royal party written in a then new vernacular which might be described as 'officer facetious'. This had been de- veloped in the first world war by H. C. McNeile who wrote under the name of Sapper, glorifying the military adventures of British gentlemen soldiers. His patriot- ism was an illegitimate descendant of Kipling's but as the majority of the regular army's upper-class officers had been killed in 1914-15 and replaced from the middle and lower classes, who before the war would never have dreamt of embarking on military careers, a new patriotic instructor and seer was needed to tell the new entry how dashing 'officers and gentlemen' should behave. Sapper filled the bill and told his eager pupils how to be 'white' through and through, a perfect gentleman in the Robin Hood style, and at the same time how to beat up and kill Huns, wogs and dagos. He was a brilliant story-teller, and despite his inability to write a sentence of grammatical English, his phraseology became adopted by the services and echoes are still to be distinctly heard in their three messes today. Sapper was an unfortunate model for the illiterate young Mountbat- ten, who was totally ignorant of the arts and graces and devoid of humanism. The diaries are an unnecessary publication, often acutely embarrassing. To begin with, echoing his mentor, he was facetious about nomenclature and refers to the Prince of Wales as 'HRH' no less than 260 times in the first 41 pages: . . . The route was lined with troops and a great crowd of people who cheered wildly as HRH passed. At Government House HRH got out, shook hands with Lord Liverpool for the third time, and went into the ball room, where Mr Massey read HRH an address on behalf of the Government of New Zealand and presented him with a casket of native wood. HRH and party . . .

Repetition kills a good joke, let alone a bad one: in this case it is insupportable as is the author's habit of referring to himself coyly as 'the Flag Lieutenant' and the other ADCs as 'Lord Claud' and 'the Hon Piers'.

The trip was full of horseplay and the author thought it very funny to flood a colleague's cabin twice, and sidesplitting to pull off Hamilton's pants: . . . Lord Claud, in trying to jump over the Admiral, upset both himself and the Admiral. When Lord Claud came to, he found HRH sitting on his head, the Admiral unbuttoning his braces, and the remainder of the Staff busily employed in removing his boots, socks, trousers and, horrible to relate, even the rest of his nethergarments. Nevertheless, he be- haved as a soldier should, and as he pattered past the sentry, orderly, and the two messen- gers, in his bare legs, he found time for a pleasant word with each of them.

The royal party also found it funny to throw people out of windows, call them in the middle of the night and behave in every way like boys of 14 on a tutorless rampage. Throughout their journeys, contempt for `lesser breeds without the law' was exhi- bited by the future socialist Viceroy. He called Mexicans 'copper-coloured gentle- men,' Germans 'Huns,' Egyptians `na- tives', welcoming Barbadians 'crowds of niggers' and also remarked that their streets were 'thronged with niggers'. And India?

The Nawab of Bahawalpur, who is only 17 but looks considerably more, as indeed all these young natives do . .

As for the future, the young visitor was dubious about concessions:

The trouble is their reforms please neither the natives nor the British.

New Zealanders and Australians also came in for a lot of facetious mockery and the diary plainly suggests the Prince of Wales was bored to death by naive displays of old-fashioned loyalty in colonies which had recently sacrificed thousands of their young men to help Britain win the war. It was therefore lucky the diary was not published when a copy was stolen by the ship's doctor who was caught attempting to sell it to the press. Ziegler, I feel, was unhappy editing this book. He admits to reducing its length by half. I deplore his conservatism_ Apart from Mountbatten's condescension to those who were doing their best, a previously unknown, sadistic side to his character is shown. Consider his treatment of one of his friends: . . . I touched my near bullock amidships with my finger and he at once whisked it away with his tail. This rather amused me, so I called out to Godfrey, 'Come and touch this bullock and something very funny will happen to you.' So Godfrey, very trustingly, put his finger on the spot indicated, whereupon the old bullock let fly with his hind leg and caught him on the upper part of his leg. The look of pained surprise that crossed Godfrey's face as he staggered back kept me in fits of laughter the whole afternoon, I regret to say.

But this jest was preferable to the royal party's brutality in killing defenceless, peaceful animals. Mountbatten's ambition was to shoot a kangaroo with a revolver but he had to make do with hunting, and 'arrived in time to see the kill, the dogs bringing down a kangaroo and worrying it to death.'

One was not enough, and another hunt followed about which the author had some qualms.

. . . Although it is great fun while the hunt is in progress, it is not a pleasant sight to see a kangaroo being worried to death, as they turn up great pathetic eyes at one and never utter a sound. The tail was cut off, and, as no one else wished to keep it, the Flag Lieutenant kept it.

Curious to keep a memento of such an event. The 'great pathetic eyes' did not deter him from immediately joining in the chase of another animal: . . . The five dogs were too much for him, and they all fastened on to him practically simul- taneously, so that he was pulled over and left almost powerless. Nevertheless, he took much longer to kill than the previous two.

Neither did the sportsmen neglect emus, unaware they were protected. These were also hunted by kangaroo dogs. Louis zest- fully relates the triumphant conclusion of a chase when an emu . . . made his one mistake, for he stood in the middle of a pool until driven on, and then went off to another pool of water where one of the kangaroo dogs, making a leap, caught him in the hind quarters and killed him. To speed his death several of the party broke branches off the trees and hit him over the head. After this they plucked feathers out and stuck them in their hats.

Such stories will hardly help the Duke of Edinburgh's 'Preserve Wild Life' cam- paign.

Later the party toured India and Burma and Japan and again Lord Louis is con- stantly condescending about the locals' attempts to amuse them, although he was not shocked when a gladiatorial fight be- tween a panther and a bear was put on for his benefit. Tigers and boars were inces- santly killed whenever the royal party was not playing polo, but silence reigns con- cerning Indian culture and not a single book is mentioned in the whole diary, while in Japan the only things the young Louis learned were how to catch rising ducks in nets and the rules of wrestling.

Where the diary fundamentally fails is that it sets out to be funny in a second-rate style and not tell the truth. There were two interesting events during the trip; the first when the author became engaged to a beautiful and enormously rich girl — this is mentioned and dismissed without revealing his feelings. When he leaves her she passes out of the diary without trace. The second is the Prince of Wales's behaviour. His actions are flatteringly reported, his sulki- ness and bad manners varnished over but his character is ignored and the author, not the heir to the throne, becomes the star of the show.

It is difficult to understand why the present Lady Mountbatten agreed to the publication of these diaries. They add nothing to our knowledge of her father and make him out to be a heartless and unpleasant young man. Such ,disclosures are unfair and unnecessary. He had behind him a career among men trained to vio- lence. He was only 20, and was young for his age, which made him still think it funny to be heartless, cruel and brag about hangovers and brawls. Practically every boy of his generation would, to his later regret, have written the same sort of adolescent nonsense if he had been told to write a diary. Alas, we are threatened with more volumes which will show us further glimpses of Lord Louis's intellectually arid youth. Very few young men's thoughts are worth recording; his were certainly not, as they show no glimpse of the talents which marked his extraordinary career. Lady Mountbatten should be merciful to both the reading public and her father and forget the next few years of his life.

The following lines were omitted from the review of Lenin: The Novel, by Alan Brien (14 November) in which Andrei Navrozov referred to Lenin disorganising the famine committee by 'employing informants who joined the committee under false pre- tences':

Vladimir Ilyich would enjoy this hugely, while in the committee our appearance at its almost secret meetings would cause depress- ion and irritation.

Having routed the committee by November 1891, young Lenin could rest from his labours. The New Year's party was The first big evening party in which Vladimir Ilyich took part. . . Vladimir Ilyich had to hop the quadrille for all he was worth.

Previous page

Previous page