Theatre

An Ideal Husband (Globe) Lost in Yonkers (Strand) Three Birds Alighting on a Field (Royal Court)

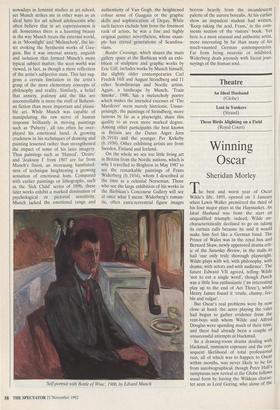

Winning Oscar

Sheridan Morley

The best and worst year of Oscar Wilde's life, 1895, opened on 3 January when Lewis Waller premiered the third of his four major plays at the Haymarket. An Ideal Husband was from the start an unqualified triumph: indeed, Wilde un- characteristically declined to go on taking its curtain calls because he said it would make him feel like a German band. The Prince of Wales was in the royal box and Bernard Shaw, newly appointed drama crit- ic of the Saturday Review, in the stalls to hail 'our only truly thorough playwright. Wilde plays with wit, with philosophy, with drama, with actors and with audience'. The future Edward VII agreed, telling Wilde `not to cut a single word', though Punch was a little less enthusiastic '(`an interesting play up to the end of Act Three'), while Henry James found it 'crude, clumsy, fee- ble and vulgar'.

But Oscar's real problems were by now close at hand: the actor playing the valet had begun to gather evidence from the rent-boys with whom Wilde and Alfred Douglas were spending much of their time, and there had already been a couple of unsuccessful attempts at blackmail.

So a drawing-room drama dealing with blackmail, imminent exposure and the con- sequent likelihood of total professional ruin, all of which was to happen to Oscar within months, was never likely to be far from autobiographical, though Peter Hall 5 sumptuous new revival at the Globe follows usual form by having the Wildean charac- ter seen as Lord Goring, who alone of the principals is free of all guilt. But the mira- cle of the play is its constant topicality, so that now the undertones are of Mellor and I raqgate rather than anything more his- toric. Indeed Goring's plaintive cry, `Nobody is incapable of doing a foolish thing; nobody is incapable of doing a wrong thing', might now usefully be inscribed-over the Palaces of Westminster and Bucking- ham as a warning for all who enter there.

Hall intelligently and sensitively pitches his production roughly halfway from Lyceum melodrama to Haymarket high comedy, heavy on set and costumes and starry support (Michael Denison apparent- ly on loan from the Garrick, Dulcie Gray cascading from the stairs); but it retains an elegantly sinister quality, never allowing us to forget the play's constant relevance to Oscar's own downfall and to the media power politics of the intervening century. David Yelland is a little nebulous as Chiltern, but Martin Shaw is a strongly Wildean Goring, and as the two female furies Anna Carteret and Hannah Gordon are superbly matched.

At the Strand, Neil Simon's Lost in Yonkers has arrived bearing a Pulitzer Prize from Broadway but lacking in my view the tremendous autobiographical strengths of his childhood trilogy, the one that started with Brighton Beach Memoirs. Here too we have the suburban New York family facing up to the second world war with a mix of immigrant despair and New World opti- mism: Rosemary Harris is the battle-axe grandmother; Maureen Lipman, Ron Ber- glas and Rolf Saxon the children she has killed with unkindness; Benny Grant and Ross McCall the grandchildren determined to get out from under. All give strong per- formances, with Lipman at her most touch- ing as the retarded spinster searching for love in cinemas and Berglas very funny as the Mafia hitman still terrified of Mom. But something is lacking here, and it is, I think, Simon's usual ability to find himself in the family snapshot and then act as its guide.

Back to the Royal Court, a year or so after its premiere, comes Timberlake Wertenbaker's Three Birds Alighting on a Field, the play that does for the Eighties art market what Serious Money did for the City. The play's thesis Cart is sexy; art is money; art is money-sexy-social-climbing- fantastic') is simple enough: that in the fluctuating valuations put on a painting even a blank, white canvas — can be seen a metaphor for the valuations we put on soci- ety and ourselves within it.

Max Stafford-Clark's fluid, agile, spare staging assembles the characters as figures in a landscape of modern Britain, centred on Harriet Walter's still stunning star turn, and the result (in a tightened and trimmed script, mercifully now without its Greek interlude) is a morality play about the way we lived out the last decade. Hopefully it may also now be an epitaph for the Eight- ies.

Previous page

Previous page