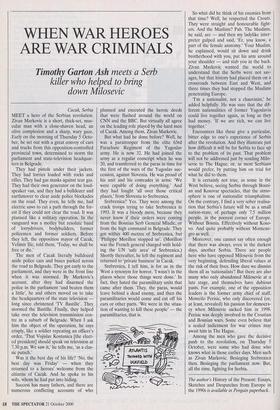

WHEN WAR HEROES ARE WAR CRIMINALS

Timothy Garton Ash meets a Serb

killer who helped to bring down Milosevic

Cacak, Serbia MEET a hero of the Serbian revolution. Zivan Markovic is a short, thick-set, mus- cular man with a close-shaven head, an olive complexion and a sharp, wary gaze. Early on the morning of Thursday 5 Octo- ber, he set out with a great convoy of cars and trucks from this opposition-controlled provincial town, determined to storm the parliament and state-television headquar- ters in Belgrade.

They had pistols under their jackets. They had lorries loaded with rocks and rifles. They had gas masks against tear gas. They had their own generator on the loud- speaker van, and they had a bulldozer and earthmover to clear aside police blockades on the road. They even, he tells me, had electric saws to cut a path through the for- est if they could not clear the road. It was planned like a military operation. In the vanguard was a motley but resolute band of lorrydrivers, bodybuilders, former policemen and former soldiers. Before they left, the opposition mayor of Cacak, Velimir Ilic, told them, 'Today, we shall be free or die.'

The men of Cacak literally bulldozed aside police cars and buses parked across the road to Belgrade. They got early to the parliament, and they were in the front line when it was stormed. By Markovic's account, after they had disarmed the police in the parliament 'and beaten them a little', he and others moved on to take the headquarters of the state television long since christened 'TV Bastille'. They stormed the Bastille. Finally, they helped take over the television transmission cen- tre in a suburb of Belgrade. When I ask him the object of the operation, he says crisply, like a soldier repeating an officer's order, 'That Vojislav Kostunica [the elect- ed president] should speak on television at 7.30 p.m. We saw it,' he tells me, 'as a clas- sic putsch.'

Was it the best day of his life? 'No, the best day was Friday' — when they returned to a heroes' welcome from the citizens of Cacak. And he spoke to his wife, whom he had put into hiding.

Success has many fathers, and there are numerous conflicting accounts of who planned and executed the heroic deeds that were flashed around the world on CNN and the BBC. But virtually all agree on the leading role played by the hard men of Cacak. Among them, Zivan Markovic.

But what had he done before? Well, he was a paratrooper from the elite 63rd Parachute Regiment of the Yugoslav army. He is now 32. He had joined the army as a regular conscript when he was 20, and transferred to the paras in time for the first of the wars of the Yugoslav suc- cession, against Slovenia. He was proud of his unit and his comrades in arms: 'We were capable of doing everything.' And they had fought 'all over those critical places,' from Slovenia to Srebrenica.

Srebrenica? Yes. They were among the crack troops trying to take Srebrenica in 1993. It was a bloody mess, because they never knew if their orders were coming from the Bosnian Serb General Mladic, or from the high command in Belgrade. They got within 400 metres of Srebrenica, but `Philippe Morillon stopped us'. (Morillon was the French general charged with hold- ing the UN 'safe area' of Srebrenica.) Shortly thereafter, he left the regiment and returned to 'private business' in Cacak.

Srebrenica, I tell him, is for us in the West a synonym for horror. 'I wasn't in the places where those things were done.' In fact, they hated the paramilitary units that came after them. They, the paras, would leave behind a dead enemy, and then the paramilitaries would come and cut off his ears or other parts. 'We were in the situa- tion of wanting to kill these people' — the paramilitaries, that is. So what did he think of his enemies from that time? Well, he respected the Croats. They were straight and honourable fight- ers. And the Muslims? Pah. The Muslims, he said, are — and then my ladylike inter- preter gulped and said, 'Er, you know, a part of the female anatomy.' Your Muslim, he explained, would sit down and drink brotherhood with you, put his arm around your shoulder — and stab you in the back. Zivan Markovic wanted the world to understand that the Serbs were not sav- ages, but that history had placed them on a crossroads between East and West, and three times they had stopped the Muslims penetrating Europe.

`I'm a nationalist, not a chauvinist,' he added helpfully. He was sure that the dif- ferent nationalities of former Yugoslavia could live together again, as long as they had money. 'If we are rich, we can live together.'

Encounters like these give a particular, bitter edge to one's experience of Serbia after the revolution. And they illustrate just how difficult it will be for Serbia to face up to the problem of its past. That problem will not be addressed just by sending Milo- sevic to The Hague, or, as most Serbians would prefer, by putting him on trial for what he did to them.

It is certainly not true, as some in the West believe, seeing Serbia through Bosni- an and Kosovar spectacles, that the atmo- sphere is one of nationalist triumphalism. On the contrary, I find a very sober realisa- tion that Serbia's future will be as a small nation-state, of perhaps only 7.5 million people, in the poorest corner of Europe. Without Bosnia. Effectively without Koso- vo. And quite probably without Montene- gro as well.

Moreover, one cannot say often enough that there was always, even in the darkest days, another Serbia. There are people here who have opposed Milosevic from the very beginning, defending liberal values at the risk of their lives. How dare we dismiss them all as 'nationalists'! But there are also many who only abandoned Milosevic at a late stage, and themselves have dubious pasts. For example, one of the opposition leaders is the former army chief of staff, Momcilo Perisic, who only discovered (or, at least, revealed) his passion for democra- cy when Milosevic sacked him in 1998. Perisic was deeply involved in the Croatian and Bosnian wars. Some even believe that a sealed indictment for war crimes may await him in The Hague.

Among the men who gave the decisive push to the revolution, on Thursday 5 October, were some who had done who knows what in those earlier days. Men such as Zivan Markovic. Besieging Srebrenica then. Besieging the parliament now. But, all the time, fighting for Serbia.

The author's History of the Present: Essays, Sketches and Despatches from Europe in the 1990s is available in Penguin paperback.

Previous page

Previous page