BOOKS

Perfection in a small space

Philip Hensher

THE MEANS OF ESCAPE by Penelope Fitzgerald Flamingo, £12.99, pp. 117 THE HAUNTED DOLL'S HOUSE AND OTHER STORIES by M. R. James, with an introduction by Penelope Fitzgrald Penguin Classics, £6.99, pp. 240 The short stories in The Means of Escape represent the last statement of a great writer. I hope not, in a way; it is possible that there is more. Penelope Fitzgerald was not someone who needed to share her creative processes with anyone, and there may be more to be discovered. She died five years after her last novel, and no one knows what may surface from her papers. The last time I saw her, I blithely asked her if she was writing anything, and was given a brisk, ladylike Fitzgerald brush- off. If she was, she would not have said. In life, she paid little attention to her manuscripts or her letters; her biographers, of which there will be many, will have quite a task. It is really not inconceivable that there is a last novel, or that more short stories will surface. A tenth novel would have the value, in English literature, of an unknown work by Lawrence, Conrad or Waugh. That is not to overstate the case. Of all the novelists in English of the last quarter century, she has the most unarguable claim on greatness.

This must be regarded as a provisional collection of Fitzgerald's short stories, since she does not seem to have kept them, once written or published, and it is quite likely that an old edition of a little maga- zine somewhere will yield another. That spirit of self-obliteration which, in the nov- els, allows her to enter with complete absorption into an extraordinary range of lives arose from someone without unneces- sary vanity. It is worth noticing that in her great biography of her father and his uncles, The Knox Brothers, she makes abso- lutely no personal entrance. She must have known exactly how good she was, but it is somehow appropriate that she kept no scrap-book. She would not have been one of those writers who virtually keep a shrine to themselves in their homes. The first posthumous attempt may, therefore, turn out to be The Collected Stories; or it may not. Difficult to know how much effort she put into pursuing the short-story form, but, certainly, there are at least four stories here which have a degree of perfection which could only be attained, one feels, by practice.

Introducing a Penguin selection of M. R. James's short stories (her last piece of writ- ing), Fitzgerald homes in unerringly on the inexplicable elements, the irrational moments which probably its writer could not fully explain. Writing of The Stalls of Barchester Cathedral', she particularly admires the placing of the line 'There is no kitchen cat'; something which arises out of nothing, and condenses the whole terror of the story, and looks utterly banal out of context. In what Fitzgerald calls 'the best story [James] ever wrote',`The Story of a Disappearance and an Appearance', what she admires is the inexplicable dream in which the murdered uncle makes an appearance.

Monty does not explain why he should be there, and seems to have come in this story as close as he ever did to compulsive writing, or being carried away.

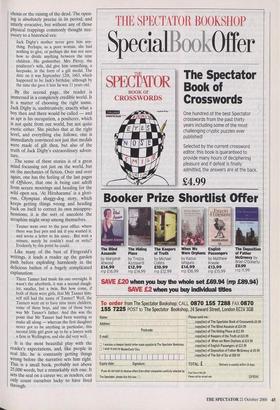

James fascinated Fitzgerald. In part it was the period of pre-Great War academic life, which she loved; one of her best nov- els, The Gate of Angels, is set in Cambridge in Monty's time, and contains a first-rate pastiche of a James short story, and The Knox Brothers is a long teasing-out of that particular intellectual world. But mostly it was one glancing, allusive, dry artist responding to another. (I feel rather smug `She keeps complaining that I never take her anywhere!' about the whole matter of the Penguin introduction; Penguin asked me to write one, and I said I would only do it if Fitzgerald declined, so much did I want to read her thoughts on him. Happily, she proved, in this instance, susceptible to temptation.) That sense, so often in James, of some- thing colossal at the last being revealed through a tiny turn of phrase, or even a sin- gle word, proved one of Fitzgerald's most remarkable devices. One would not use the expression twist in the tail', but at the end of many of her most marvellous things there is a sense of a great window suddenly opening. The last sentence of her Russian novel, The Beginning of Spring, resolves the whole drama; at the end of The Gate of Angels, a door opens and everything changes; the entire tragedy of her great last novel, The Blue Flower, is contained in the epilogue.

That visionary final twist of the screw is unforgettably indulged in these short sto- ries. If you miss the significance of the word 'a watch' in the last paragraph of 'The Red-Haired Girl', you will not just not understand the depth of love the heroine bears for its painter hero, but miss the point of the whole story. There is a glorious twist at the end of 'The Means of Escape' when we realise that we, as well as its sad heroine, have entirely misconstrued the motives of the escaped convict. Most impressive, in every sense, is the terrifying conclusion of her earliest published work of fiction, the ghost story 'The Axe', when nothing is happening, nothing is seen, and one can hardly read on: If what I have next door is a visitant which should not be walking but buried in the earth, then its wound cannot bleed, and there will be no stream of blood moving slowly under the whole width of the communicating door. However I am sitting at the moment with my back to the door, so that, without turning round, I have no means of telling whether it has done so or not.

Fitzgerald has a famous ability to recre- ate remote and fantastic worlds in her nov- els; the declining Italian aristocracy in Innocence, or the perfect solidity of a little German principality in the 1790s in The Blue Flower. One never had the sense that this solidity was achieved through weight of detail, rather by the single, perfectly chosen detail, and in the shorter space of the short story she calls up similarly exotic settings. The most perfect of the stories here, `Desideratus', is set in the late 17th centu- ry, as a poor boy is trapped in a great house and dragged into a mysterious and sinister ritual, perhaps involving metempsr chosis or the raising of the dead. The open- mg is absolutely precise in its period, and utterly evocative, but without any of those physical trappings commonly thought nec- essary to a historical era:

Jack Digby's mother never gave him any- thing. Perhaps, as a poor woman, she had nothing to give, or perhaps she was not sure how to divide anything between the nine children. His godmother, Mrs Piercy, the poulterer's wife, did give him something, a keepsake, in the form of a gilt medal. The date on it was September 12th, 1663, which happened to be Jack's birthday, although by the time she gave it him he was 11 years old.

By the second page, the reader is immersed in a completely credible world. It is a matter of choosing the right name. Jack Digby is, unobtrusively, exactly what a boy then and there would be called — and as apt is his occupation, a poulterer, which is not quite from our world, but not quite exotic either. She pitches that at the right level, and everything else follows; one is immediately convinced not just that medals were made of gilt then, but also of the truth of Jack Digby's extraordinary adven- ture.

The sense of these stories is of a great mind focussing not just on the world, but on the mechanics of fiction. Over and over again, one has the feeling of the last pages of Offshore, that one is being cast adrift from secure moorings and heading for the wild open sea. 'At Hiruharama' is a glori- ous, Olympian shaggy-dog story, which keeps getting things wrong and heading back on itself to correct its own misappre- hensions; it is the sort of anecdote the seraphim might swap among themselves.

Tanner went over to the post office, where there was free pen and ink if you wanted it, and wrote a letter to his sister. But wait a minute, surely he couldn't read or write? Evidently by this point he could.

Like many of the best of Fitzgerald's writings, it leads a reader up the garden path before exploding harmlessly in the delicious bathos of a hugely complicated explanation:

There Tanner had made his one oversight. It wasn't the afterbirth, it was a second daugh- ter, smaller, but a twin. But how come, if both of them were girls, that Mr Tanner him- self still had the name of Tanner? Well, the Tanners went on to have nine more children, some of them boys, and one of those boys was Mr Tanner's father. And this was the point that Mr Tanner had been wanting to make all along — whereas the first daughter never got to be anything in particular, this second little girl grew up to be a lawyer with a firm in Wellington, and she did very well.

It is the most beautiful play with the reader's expectations, and, like people in real life, he is constantly getting things wrong before the narrative sets him right. This is a small book, probably not above 25,000 words, but a remarkably rich one. It sets the seal on a career we, as readers, can only count ourselves lucky to have lived through.

Previous page

Previous page