ARTS

Exhibitions 1

Once was enough

Giles Auty

The Pop Art Show (Royal Academy, till 15 December) Objects for the Ideal Home: the Legacy of Pop Art (Serpentine Gallery, till 20 October) Five Artists: English and American Pop Prints from the Sixties (Waddington Galleries, till 26 October)

0 f those who had reached at least notional adulthood by that time, the world might be divided conveniently into those who do and those who do not feel unquali- fied enthusiasm for the so-called culture of the Sixties. I am of the latter persuasion

while the art critic of the Daily Telegraph seems just as clearly of the former. Writing about The Pop Art Show at the Royal Academy in last Friday's paper, Mr Dor- ment quotes the man he calls Pop Art's spiritual godfather, Marcel Duchamp, in defence of his partiality: 'Of all the many profound things Duchamp had to say about art, the most important for the origins of Pop is this: "Life is more interesting than Art".'

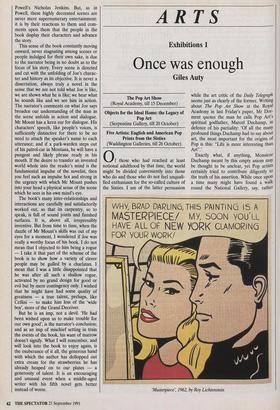

Exactly what, if anything, Monsieur Duchamp meant by this empty axiom may be thought to be unclear, yet Pop artists certainly tried to contribute diligently to the truth of his assertion. While once upon a time many might have found a walk round the National Gallery, say, rather `Masterpiece, 1962, by Roy Lichtenstein

more illuminating than an evening of fire- side wisdom among Sun readers in Toot- ing, Pop Art set out singlehandedly to alter the equation. The advent of Pop was the first time that any art became even less interesting than the more mundane acts of everyday existence. Art became as boring as mass culture because it was mass cul- ture. And those unfortunates who sought to escape the ubiquity of packaging and billboards, comics and cheap magazines by seeking sanctuary in an art gallery became doomed to sudden disappointment. While Pop artists may have congratulated them- selves fondly on their imagined sense of irony and irreverence, most viewers were utterly unaware of these: bland simply looked bland to them.

And at whom, in any case, was such hypothetical irreverence directed? Admit- tedly there had been a high seriousness about much of the preceding, largely abstract museum art of the Fifties, yet soon Pop Art's practitioners were being feted every bit as solemnly by the museum world, without too many squeaks of complaint. Pop artists scorned the idealism and earnestness of their predecessors and became the first generation of artists to present themselves as tough-talking busi- nessmen. As early as 1957, Richard Hamil- ton, one of the founding fathers of Pop Art in Britain, proposed the following qualities for 'truly modern art': 'popularity, tran- sience, expendability, wit, sexiness, gim- mickry and glamour. It must also be low-cost, mass-produced, young and Big Business'.

Art which desires to be expendable and ephemeral ought to have no trouble in ful- filling its aims. Why, then, are we visited now with a second coming of original Pop, at the Royal Academy and elsewhere, and with the acts of its latter-day apostles at the Serpentine Gallery?

It is not the best-kept secret that the commercial art market has suffered severe- ly during the recent recession. Is it too far- fetched to imagine prominent art dealers and administrators meeting to discuss sur- vival strategy in a bunker beneath Bond Street or Burlington House? 'Let's give them a dose of Pop,' someone suggests, `After all, almost everyone loves Pop Art — or thinks that they ought to.' `Publicity won't be a problem,' another avers, 'espe- cially if we could get a national newspaper involved.' What a wonderful wheeze,' a third Popsqueak pipes up. 'But how could an independent newspaper be persuaded to throw real editorial weight behind our plan?' The precise workings of the art world are hardly less mysterious and arcane than the rites of the Rosicrucians and are probably not fit subject for the minds of mere laymen to dwell upon.

On the evening of my attendance at the Royal Academy's exhibition I discussed the phenomenon of Pop Art with an artist of genuine distinction. Both of us were in our early twenties when the Sixties began. Nei- ther at that time nor since has either of us found anything in Pop Art which might interest lovers of serious painting. Pop Art ignores most or all of the real problems of making art, or simply pretends these don't exist. Some art critics, like Mr Dorment of the Daily Telegraph, feel Pop Art has changed the nature of art forever, whereas I do not consider it has affected serious art in the slightest. A number of practitioners of Pop Art became very rich both in Amer- ica and Britain. Yet while this fact may be of great interest to readers of tabloids it should not influence the opinions of civilised people. Warhol owned some 800 wigs at the time of his death. Is this more or less interesting than the anaesthetising presence of his art? The decision is a finely balanced one.

Many debate similarly whether British artists or American had the greater influ- ence on the original language and formula- risations of Pop. Were Johns, Warhol, Lichtenstein and Wesselmann more or less influential than Hamilton, Tilson, Paolozzi and Blake? The matter seems, at best, of marginal interest. The artists I prefer from either country are the more peripheral and hard-to-classify figures: the sculptors Segal and Oldenburg from America, the painters Kitaj, Hockney, Self and Jones from Britain. The work of each of these last relates to an aesthetic of more than 15 minutes' duration.

While limited in my enthusiasm for most of the work at the Royal Academy, I must admit I found the work by second- generation Popsters at the Serpentine of almost unimaginable boredom and banali- ty. I cannot conceive that there is any plea- sure or satisfaction to be obtained in the making of the trivial artefacts of Opie, Koons, Noland, Artschwager, Armleder, Wentworth or most of the rest. Yet several of these artists have acquired considerable wealth and fame already in the cloud cuck- oo land that is the market-place for con- temporary art. I do hope, however, that each would-be artist has a spare-time hobby which supplies the element of satis- `If it goes down well with the rats I'll do a gig for the kids next week.' faction which must be missing so clearly from their lives. Canasta and crochet would surely seem life-enhancing by comparison- with the vapidity of their daily grind.

At Waddington Galleries (12 & 34 Cork Street and 16 Clifford Street, W1) five of the senior generation of British Pop artists show that some, at least, have left childish things behind and tried to rejoin the deeper-flowing mainstream of art. In spite of a week which has witnessed a two-and-a- half-hour BBC 2 documentary on Pop Art of truly terrifying vacuity and all the eulo- gies of my colleagues, perhaps there's some hope for art after all.

Previous page

Previous page