The Empress and I

Amit Chaudhuri

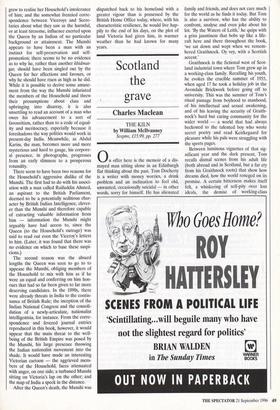

INDIAN SAHIB by Sushila Anand Duckworth, £16.95, pp. 112

In 1887, 24-year-old Abdul Karim, son of a humble hakim (a Muslim doctor) and scion of a family in no particular way dis- tinguished, arrived in England to wait upon the Queen. It was the year of Queen Victo- ria's Golden Jubilee. As Sushila Anand says towards the beginning of her book, which is primarily an account of Abdul Karim's relationship with Victoria: In celebration of her Jubilee the Queen had been sent a unique present, nothing less than a pair of Indian servants ... It was planned that the Indians should act as khitmatgars [sic], or table servants, in the first instance, and gradually be put to other useful tasks.

Anand informs us that more Indians arrived, forming a distinctive group within the Queen's menage. One of the first was Abdul Karim.

Abdul Karim rose from the position of khidmatgar to Munshi, or teacher, a title he would be known by even when he had attained, through the Queen's good offices and efforts, the exalted position of the Queen's Indian Secretary; later, he would even be made a Companion of the Indian Empire. But it was in his capacity as Munshi that Abdul Karim impressed the Queen and even endeared himself to her, and she was to become 'his willing pupil in Hindustani and Urdu,' noting in her jour- nal, 'It is a great interest to me, for both the language and the people I have natu- rally never come into real contact with before.'

This is the single most delightful revela- tion in this book. For one thing, it shows how misleadingly the epithet 'Victorian' is made synonymous with the closed and insular; for another, it tells us that the gap between the Queen and her subjects was not as great as the one between her and her administrators, who had little time for Indian culture, and who would have pre- sumably regarded the Queen's interest as an eccentricity. Abdul Karim emerges from this book as a nebulous character, about whom it is dif- ficult to arrive at any conclusion. Almost all we seem to have on record about him are the glowing, if defensive, tributes paid to him by the Queen in her letters, as she

grew to realise her Household's intolerance of him; and the somewhat frenzied corre- spondence between Viceroys and Secre- taries about what they saw as the harmful, or at least tiresome, influence exerted upon the Queen by an Indian of no particular background or attainment. The Munshi appears to have been a man with an instinct for self-preservation and self- promotion; there seems to be no evidence as to why he, rather than another khidmat- gar, should have been singled out by the Queen for her affections and favours, or why he should have risen as high as he did. While it is possible to derive some amuse- ment from the way the Munshi infuriated the members of the Household and threw their presumptions about class and upbringing into disarray, it is also unsettling to read an account of a man who owes his advancement to a sort of favouritism, rather than to a code of equal- ity and meritocracy, especially because it foreshadows the way politics would work in present-day India. Meanwhile, as Abdul Karim, the man, becomes more and more mysterious and hard to gauge, his corpore- al presence, in photographs, progresses from an early slimness to a prosperous rotundity.

There seem to have been two reasons for the Household's aggressive dislike of the Munshi. The first had to do with his associ- ation with a man called Raifuddin Ahmed, an aspirant to the British Parliament, deemed to be a potentially seditious char- acter by British Indian Intelligence, clever- er than the Munshi and therefore capable of extracting valuable information from him — information the Munshi might arguably have had access to, since the Queen (to the Household's outrage) was said to read out even the Viceroy's letters to him. (Later, it was found that there was no evidence on which to base these suspi- cions.) The second reason was the absurd lengths the Queen was seen to go to to appease the Munshi, obliging members of the Household to mix with him as if he were an equal and conferring on him hon- ours that had so far been given to far more deserving candidates. In the 1890s, there were already threats in India to the contin- uance of British Rule; the inception of the Indian National Congress and the consoli- dation of a newly-articulate, nationalist intelligentsia, for instance. From the corre- spondence and fevered journal entries reproduced in this book, however, it would appear that the main threat to the well- being of the British Empire was posed by the Munshi, his large presence throwing the Indian nationalist movement into the shade. It would have made an interesting Victorian cartoon — the aggrieved mem- bers of the Household, faces attenuated with anger, on one side; a turbaned Munshi sitting on Victoria's lap on the other; and the map of India a speck in the distance. After the Queen's death, the Munshi was dispatched back to his homeland with a greater vigour than is possessed by the British Home Office today, where, with his characteristic resilience, he would live hap- pily to the end of his days, on the plot of land Victoria had given him, in warmer weather than he had known for many years.

Previous page

Previous page