Going too far Bernard Dunstan WALTER SICKERT: DRAWINGS by Anna

Gruetzner Robins Scolar, 1115, pp. 96 Anew book on Sickert's drawings must always be welcome. Nothing on the subject has been published for some years, and though a few of his drawings are well known — 'Ennui', 'The Old Bedford', 'Jack Ashore' — there must be hundreds which

have never been reproduced at all. From

Dr Robins' new book at least 20 were quite unfamiliar to me. For this alone the book is of value to all lovers of Sickert and fine drawing; though the number and scale of the reproductions, considering the price of the book — high even by today's standards — may be called modest.

For many people besides myself this book must have had an unfortunate intro- duction in the form of a short article in The Times, the headline of which read, startlingly, 'Sickert obsessed with perver- sion'. It contained many such phrases as 'a man obsessed with the world of prostitu- tion and licentiousness', and referred to 'images of exposed female genitalia' and to 'violence, perversion and mutilation'.

It has to be said that nothing quite as sensational as this appears in the book apart from one section. Most of the text is devoted to a perfectly clear account of Sickert's use of drawings as studies for paintings, particularly in his early music- hall pictures. It is when we reach a chapter headed 'Female Models' that an unmistak- able note of censure is heard. Mentioning a

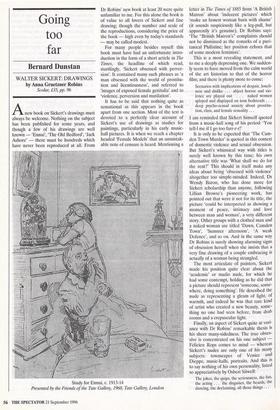

Study for Ennui, C. 1913-14

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery, 1960, Tate Gallery, London letter in The Times of 1885 from 'A British Matron' about 'indecent pictures' which 'make an honest woman burn with shame' (it sounds suspiciously like a leg-pull, but apparently it's genuine), Dr Robins says: 'The "British Matron's" complaints should not be dismissed as the remarks of a puri- tanical Philistine; her position echoes that of some modern feminists'.

This is a most revealing statement, and to me a deeply depressing one. We sudden- ly seem to have moved from the calm world of the art historian to that of the horror film; and there is plenty more to come:

Scenarios with implications of despair, loneli- ness and dislike ... abject horror and vio- lence are played out . . . naked women splayed and displayed on iron bedsteads . . . deep psycho-sexual anxiety about prostitu- tion, class, and female sexuality ...

I am reminded that Sickert himself quoted from a music-hall song of his period: 'You tell-I me if I go too farr-r-r!'

It is only to be expected that 'The Cam- den Town Murder' is quoted in this context of domestic violence and sexual obsession. But Sickert's whimsical way with titles is surely well known by this time; his own alternative title was 'What shall we do for the rent?' This should in itself make any ideas about being 'obsessed with violence' altogether too simple-minded. Indeed, Dr Wendy Baron, who has done more for Sickert scholarship than anyone, following Lillian Browse's pioneering work, has pointed out that were it not for its title, the picture 'could be interpreted as showing a moment of peace, intimacy and love between man and woman', a very different story. Other groups with a clothed man and a naked woman are titled 'Dawn, Camden Town', 'Summer afternoon', 'A weak Defence', and so on. And in the same way Dr Robins is surely showing alarming signs of obsession herself when she insists that a very fine drawing of a couple embracing is actually of a woman being strangled.

The most articulate of painters, Sickert made his position quite clear about the 'academic' or studio nude, for which he had some contempt, holding as he did that a picture should represent 'someone, some- where, doing something'. He described the nude as representing a gleam of light, of warmth, and indeed he was that rare kind of artist who created a new beauty, some- thing no one had seen before, from drab rooms and a crepuscular light. Finally, an aspect of Sickert quite at vari- ance with Dr Robins' remarkable thesis is his sheer many-sidedness. The true obses- sive is concentrated on his one subject — Felicien Rops comes to mind — whereas Sickert's nudes are only one of his many subjects: townscapes of Venice and Dieppe, music-halls, portraits. And this is to say nothing of his own personality, listed so appreciatively by Osbert Sitwell:

The jokes, the quips, the seriousness, the fun, the acting ... the disguises, the beards, the dancing, the declaiming, all those things ...

Previous page

Previous page