Exhibitions

Mysteries of Ancient China (British Museum, till 5 January 1997)

Obsession with death

Martin Gayford

The First Emperor of China ordered all the ancient books in his empire to be burnt and the execution of 460 scholars guilty of hiding their libraries. Down the centuries, his action has become a paradigm of the ultimate impotence of tyranny. The written word survived; he died. But more recently it has begun to look as if the Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi may after all have had a sort of victory over time. Many of the extraordi- nary and beautiful objects on display in Mysteries of Ancient China would not exist at all if it had not been for the yearnings for immortality felt by Qin and his culture. The ancient Chinese, like so many peo- ples, were death-obsessed. And, as is also common, they were inclined to imagine the after-life as a reflection of this one. So, in their case, beyond the grave lay an imperial bureaucracy administered by powerful offi- cials. Some of the grave goods exhibited, it is argued, constituted corroboration that the deceased really were as important as they claimed to be. A perfect model of a country mansion, or a tower for storing grain, was posthumous proof of wealth and position.

Other objects, it seems, were buried so that within the tomb the dead could contin- ue to enjoy the gracious style of life that they had led above the ground. So — in the form of clay statuettes — dancing girls, ser- vants and dwarf jesters were interred with the corpse. In the case of Qin —the ancient Chinese Napoleon who unified the empire, built the Great Wall, imposed uniform cur- rency, and weights and measures — much more was required to maintain his imperial life-style in perpetuity.

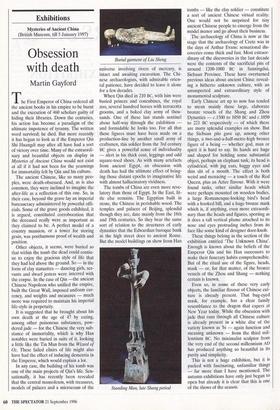

It is suggested that he brought about his own death at the age of 47 by eating, among other poisonous substances, pow- dered jade — for the Chinese the very sub- stance of immortality, which is why Han notables were buried in suits of it, looking a little like the Tin Man from the Wizard of Oz. These failed elixirs of life might also have had the effect of inducing dementia in the Emperor, which would explain a lot. In any case, the building of his tomb was one of the main projects of Qin's life. Sen- sationally, it has recently been revealed that the central mausoleum, with treasures, models of palaces and a microcosm of the Burial garment of Liu Sheng universe involving rivers of mercury, is intact and awaiting excavation. The Chi- nese archaeologists, with admirable orien- tal patience, have decided to leave it alone for a few decades.

When Qin died in 210 BC, with him were buried princes and concubines, the royal zoo, several hundred horses with terracotta grooms, and a baked clay army of thou- sands. One of these last stands sentinel about half-way through the exhibition and formidable he looks too. For all that these figures must have been made on a production-line by another small army of craftsmen, this soldier from the 3rd century BC gives a powerful sense of individuality — alert in his thick coat, leggings and odd square-toed shoes. As with many artefacts from ancient Egypt, an obsession with death has had the ultimate effect of bring- ing those distant epochs to imaginative life with almost hallucinatory vividness.

The tombs of China are even more reve- latory than those of Egypt. In the East, lit- tle else remains. The Egyptian built in stone, the Chinese in perishable wood. The temples and palaces of Beijing, splendid though they are, date mainly from the 18th and 19th centuries. So they bear the same sort of relation to the structures of early dynasties that the Edwardian baroque bank in the high street does to ancient Rome. But the model buildings on show from Han Standing Man, late Shang period tombs — like the clay soldier — constitute a sort of ancient Chinese virtual reality. One would not be surprised for tiny ancient Chinese people to emerge from the model manor and go about their business.

The archaeology of China is now at the stage that the archaeology of Crete was in the days of Arthur Evans: sensational dis- coveries come thick and fast. Most extraor- dinary of the discoveries in the last decade were the contents of the sacrificial pits of around 1200-1000 BC in Sanxingdui, Sichuan Province. These have overturned previous ideas about ancient China: reveal- ing a hitherto unknown culture, with an unsuspected and extraordinary style of monumental sculpture.

Early Chinese art up to now has tended to mean mainly those large, elaborate bronze vessels of the Shang and Zhou Dynasties — c.1500 to 1050 BC and c.1050 to 221 BC respectively — of which there are many splendid examples on show. But the Sichuan pits gave up, among other things, a two-and-a-half-metre-high bronze figure of a being — whether god, man or spirit it is hard to say. Its hands are huge and shaped for holding some substantial object, perhaps an elephant tusk; its head is cylindrical, with jug ears, baggy eyes and thin slit of a mouth. The effect is both weird and menacing — a touch of the Red Queen, plus an Aztec flavour. With it were found tusks, other similar heads which were perhaps mounted on wooden bodies, a large Romanesque-looking bird's head with a hooked bill, and a huge bronze mask which is, if anything, even more extraordi- nary than the heads and figures, sporting as it does a tall vertical plume attached to its nose and eyes protruding inches from its face like some kind of designer door-knob.

These things belong in the section of the exhibition entitled 'The Unknown China'. Enough is known about the beliefs of the Emperor Qin and his Han successors to make their funerary habits comprehensible. But of the ritual use of the figure, heads, mask — or, for that matter, of the bronze vessels of the Zhou and Shang — nothing certain is known.

Even so, in some of these very early objects, the familiar flavour of Chinese cul- ture is already present. That bug-eyed mask, for example, has a clear family resemblance to the dragon that capers at New Year today. While the obsession with jade that runs through all Chinese culture is already present in a white disc of the variety known as 'bi — again function and meaning unknown — from the third mil- lennium BC. No minimalist sculptor from the very end of the second millennium AD has produced anything so beautiful in its purity and simplicity. This is not a huge exhibition, but it is packed with fascinating, unfamiliar things — far more than I have mentioned. The autumn exhibitions have only just begun to open but already it is clear that this is one of the shows of the season.

Previous page

Previous page