American Notebook

1-tavhig New York after a month in the United States, I feel I have met no American whom I would describe as shy — no one who ever looks at his feet and blushes, who wonders how to enter a room, whether to use a fork at luncheon, whether to shake hands or not. The American looks you traight in the eye and tells you, apparently, Just what he is thinking. If you ask him how be Is, he is almost unfailingly extremely well and enjoying himself greatly at whatever he Is doing. It is impressive. Success in the United States depends, it seems, on presenting this brave face to the world. The secret sufferings of the individual are not for Public exposure. For the rich there is the shrink% for the less prosperous there is the self-help book. Yards of shelves in Amentank ookshops are filled with paperbacks °h how to survive a divorce, how to overe,(3111e depression, how to be a contented uoinosexual, and so on. They all seem to be best-sellers.

Wilkes County, North Carolina, used to call itself the world's centre of moonshine. Even °W, hidden among the pine trees of the Twer slopes of the Blue Ridge mountains, (hr are said to be stills churning out the c°rn whisky. The countryside, which is serene and beautiful, is inhabited mainly by !Ina!' farmers. One or two of them, I am f`uld, still breed cocks for illegal cockbighting. But mainly they breed chickens. eside each pleasant, weatherboarded tartnhouse now stands a long and menacing nresv chicken shed in which some 10,000 culekens live out their short lives in eternal t.wilight. With the decline of the cotton and tobacco crops, chickens have restored prosPeritY to the peasants. I inquired about one ri!r.ticularly handsome farmhouse which ,,da a wooden porch all the, way round. It ha been built, I was casually told, by the nese twins —the Siamese twins, the orig„al Chang and Eng who were born in a Vatnese fishing village in 1811 and lived for tiltY-three years with their chests joined bogether at the breastbone by a five-inch arld of flesh. Chang and Eng are among the st famous monstrosities who have ever svecd• They were discovered in 1824 by a w ottish entrepreneur, Robert Hunter, ,11,0, with an American partner, Captain 'thuel Coffin, exhibited them triumphantly 81.2%Ighout the United States and Great ritain. But at the age of twenty-one, they :Vared their independence and settled in rtil Carolina, where they managed two sitecessful farms, owned twenty-eight i,4`ies, and married two daughters of a esPerous local farmer. They became US "Izens and enjoyed the friendship and

respect of their neighbours. It seems the ultimate proof of the openness of American society.

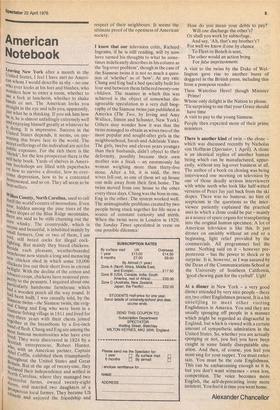

I know that our television critic, Richard Ingrains, if he is still reading, will by now have turned his thoughts to what he sometimes indelicately describes in his column as the leg-over problem', though in the case of the Siamese twins it is not so much a question of 'whether' as of 'how'. At any rate Chang and Eng had a bed specially built for four and between them fathered twenty-one children. The manner in which this was achieved is the object of somewhat disagreeable speculation in a very dull biography of the Siamese twins just published in America (The Two, by Irving and Amy Wallace, Simon and Schuster, New York). Others may wonder how it was that the twins managed to obtain as wives two of the most popular and sought-after girls in the neighbourhood, Sarah and Adelaide Yates. The girls, twelve and eleven years younger than their husbands, didn't object to their deformity, possibly because their own mother was a freak — an enormously fat woman weighing more than thirty-five stone. After a bit, it is said, the two wives fell out, so one of them set up house one mile away from their first home. The twins moved from one house to the other every three days. Chang was the boss in one, Eng in the other. The system worked well. The unimaginable problems created by two people being stuck together for life were a source of constant curiosity and mirth. When the twins were in London in 1829, the Sunday Times speculated in verse on one possible dilemma:

How do you mean your debts to pay? Will one discharge the other's?

Or shall you work by subterfuge, And say, `Ah, that's my brother's'! For well we know if One by chance To Fleet or Bench is sent, The other would an action bring

For false imprisonment.

A visit to the twins by the Duke of Wellington gave rise to another burst of doggerel in the British press, including this from a pompous reader: Thou Waterloo Hero! though Minister Prime!

Whose only delight is the Nation to please, 'Tis surprising to me that your Grace should have time A visit to pay to the young Siamese.

People then expected more of their prime ministers.

There is another kind of twin — the clone — which was discussed recently by Nicholas von Hoffman (Spectator, 1 April). A clone is an identical replica of another human being which can be manufactured, apparently, without any leg-over business at all. The author of a book on cloning was being interviewed one morning on television by one of those deadly serious interviewers with white teeth who look like half-witted versions of Peter Jay just back from the ski slopes. There was no humour, no hint of scepticism in the questions as the interviewee patiently explained the practical uses to which a clone could be put — mainly as a source of spare organs for transplanting into the original human specimen. A lot of American television is like this. It just drones on amiably without an end or a beginning, light relief provided by the commercials. All programmes feel the same. Nothing said on it — however preposterous — has the power to shock or to surprise. It is, however, as I was assured by the Dean of the Communications School at the University of Southern California, 'good chewing gum for the eyeball'. Ugh!

At a dinner in New York — a very good dinner attended by very nice people — there are two other Englishmen present. It is a bit unsettling to meet other visiting Englishmen in America. You and they are usually sponging off people in a manner which might be regarded as disgraceful in England, but which is viewed with a certain amount of sympathetic admiration in the United States. So, whether you are actually sponging or not, you feel you have beep caught in some faintly disreputable situation. And then, of course, you feel you must sing for your supper. You must entertain. You must be the cute Englishman. This can be embarrassing enough as it is, but you don't want witnesses — even less, competition. The voice becomes more English, the self-depreciating irony more insistent. You feel it is time you went home.

Alexander Chancellor

Previous page

Previous page