Moro, the conciliator

Peter Nichols

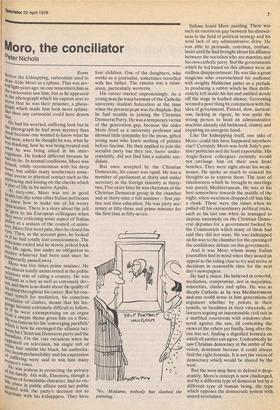

Rome 13ef0re the kidnapping, cartoonists used to draw Aldo Moro as a sphinx. That was seve,N light-years ago: no one remembers him as fie cartoonists saw him, but as he appeared in the photograph which his captors sent to prove that he was their prisoner, a photorIaph which made him look more sphinx,e than any cartoonist could have drawn m.

ti.He had his worried, suffering look but in "ie Photograph he had more mystery than j.13ual because one wanted to know what he i "ad seen, where he thought he was, what he WaS thinking, how he was being treated and what he was being asked in his inter'Nations. He looked different because he fad no tie. In normal conditions, Moro was 14:311fla1, oddly ceremonious with his deep °‘vs, but unlike many southerners some'at aver-se to physical contact such as the erobracin and kissing on the cheeks which 's Part of life in his native Apulia. h At sixty-one, Moro was not in good health but like some other Italian politicians "e knew how to make use of his weary 4,13Pearance. There is a story about the jolt t"te gave to his European colleagues when "ey were criticising some aspect of Italian Pc't hey at a session of the council of minis ( „ers. Moro first went pale, then he closed his ' `Yes. Then, so the account goes, he looked es.lf he had totally lost consciousness. The leisms ended and he slowly jerked back o life again, but under no obligation to :inswer whatever had been said since he emPorarily passed away. w Moro was five times prime minister. He r„a,s almost totally uninterested in the public ions side of ruling a country. He was "rilhant as a boy as well as extremely devrti and there is no doubt about the quality of s,s Mind throughout his career. But his conSearch for mediation, his conscious qvoidance of clashes, meant that his lanVa.ge became extremely difficult to follow, ft' lf he were extemporising on an organ 1.1°.°1 a simple theme given him on a flute. `vas famous for his 'converging parallels' we u'ell is how he envisaged the alliance bet„e.o his Christrian Democrat party and the :ocialists. On the rare occasions when he 7peared on television, his single tuft of t; illtF hair amidst the black, his authorita,...ve Mcomprehensibility and his expression r suffering were said to win him many wornen's votes.

oiilis , e was jealous in protecting the privacy family. His wife, Eleonora, though a

w family.

of formidable character, had no vis e „ Place in public affairs until her public 'Parrel with the party's decision not to 'egotiate with his kidnappers. They have four children. One of the daughters, who works as a journalist, sometimes travelled with her father. The cinema was a relaxation, particularly westerns.

His career started unpromisingly. As a young man,lhe waslchairman of the Catholic university student federation at the, time when the present pope was its chaplain. But he had trouble in joining the Christian Democrat Party. He was a temporary victim of the generation gap, because the older Moro lived as a university professor and showed little sympathy for the pious, gifted young man who knew nothing of politics before fascism. He then applied to join the socialist party but they too, more understandably, did not find him a suitable candidate.

But once accepted by the Christian Democrats, his career was rapid. He was a member of parliament at thirty and under secretary at the foreign ministry at thirtytwo. Five years later he was chairman of the Christian Democrat group in the chamber and at thirty-nine a full minister — first justice and then education. He was party secretary at fifty-three and prime minister for the first time at fifty-seven. Italians found Moro puzzling. There was such an enormous gap between his shrewdness in the field of political strategy and his total lack of any administrative drive. He was able to persuade, convince, confuse, insist until he had brought about his alliance between the socialists who are marxists and his own catholic party. But the governments which he led based on this alliance were an endless disappointment. He was like a great magician who overwhelmed his audience with weighty Mahlerian patter as a prelude to producing a rabbit which he then deliberately left inside his hat and ambled slowly off the stage in hushed silence. Governing seemed a poor thing by comparison with the idea of government. Patient, slow, meticulous, lacking in vigour, he was quite the wrong person to head an administrative machine already old-fashioned, clumsy and requiring an energetic hand.

Like the kidnapping itself, one asks of Moro: could this have happened anywhere else? Certainly Moro was both Italy's premier politician and the least exportable. His Anglo-Saxon colleagues certainly would not envisage him on their own front benches. They were right about his weaknesses. He spoke as much to conceal his thoughts as to express them. The note of timelessness which he brought to meetings was purely Mediterranean. He was at his best somewhere towards the middle of the night, when weariness dropped off him like a cloak. These were the times when he pulled off his extraordinary political tricks, such as his last one when he managed to impose unanimity on the Christian Democrat deputies for a government backed by the Communists which many of them had said they did not want. He was kidnapped on his way to the chamber for the opening of the confidence debate on this government.

And it was Moro whom many Italian journalists had in mind when they issued an appeal to the ruling class to try and arrive at decisions in reasonable time for the next day's newspapers. He had a vision. He believed in concord, mediation, compromise, not in majorities, minorities, clashes and splits. He was as deeply Catholic as he was Mediterranean and one could sense in him generations of argument whether by priests in their synods, or headmen in their vineyards, or lawyers arguing an interminable civil suit in a marbled courtroom with windows shut' tered against the sun, all contesting the views of the others yet finally, long after the 'sun has set, finding a dignified formula on which all parties can agree. Undoubtedly he saw Christian democracy at the centre of the vision, dominant because it could always find the right formula. It is not the vision of democracy which would be shared by the west.

But the west may have to defend it desperately. Moro's concept is now challenged, not by a different type of democrat but by a different type of human being, the type

e which opposes the democratic system with armed revolution.

Previous page

Previous page