BALANCING THE SCALES OF JUSTICE

Barry Wood and Alasdair Palmer investigate a Scottish murder case which has left the victim's parents dissatisfied

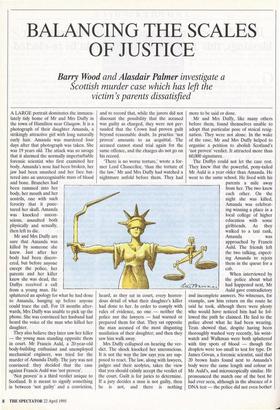

A LARGE portrait dominates the immacu- lately tidy home of Mr and Mrs Duffy in the town of Hamilton near Glasgow. It is a photograph of their daughter Amanda, a strikingly attractive girl with long naturally curly hair. Amanda was murdered four days after that photograph was taken. She was 19 years old. The attack was so savage that it alarmed the normally imperturbable forensic scientist who first examined her body. Amanda's nose had been broken, her jaw had been smashed and her face bat- tered into an unrecognisable mass of blood and bone. Branches had been rammed into her body, her mouth and her nostrils, one with such ferocity that it punc- tured her skull. Amanda was knocked uncon- scious, assaulted both physically and sexually, then left to die.

They also believe they later saw her killer — the young man standing opposite them in court. Mr Francis Auld, a 20-year-old body-building enthusiast and unemployed mechanical engineer, was tried for the murder of Amanda Duffy. The jury was not convinced: they decided that the case against Francis Auld was 'not proven'.

`Not proven' is a third verdict unique to Scotland. It is meant to signify something in between 'not guilty' and a conviction, and to record that, while the jurors did not discount the possibility that the accused was guilty as charged, they were not per- suaded that the Crown had proven guilt beyond reasonable doubt. In practice 'not proven' amounts to an acquittal. The accused cannot stand trial again for the same offence, and the charges do not go on his record.

`There is no worse torture,' wrote a for- mer Lord Chancellor, 'than the torture of the law.' Mr and Mrs Duffy had watched a nightmare unfold before them. They had heard, as they sat in court, every horren- dous detail of what their daughter's killer had done to her. In order to comply with rules of evidence, no one — neither the police nor the lawyers — had warned or prepared them for that. They sat opposite the man accused of the most disgusting mutilation of their daughter; and then they saw him walk away.

Mrs Duffy collapsed on hearing the ver- dict. The shock knocked her unconscious. It is not the way the law says you are sup- posed to react. The law, along with lawyers, judges and their acolytes, takes the view that you should calmly accept the verdict of the court. Guilt is for juries to determine. If a jury decides a man is not guilty, then he is not, and there is nothing more to be said or done.

Mr and Mrs Duffy, like many others before them, found themselves unable to adopt that particular pose of stoical resig- nation. They were not alone. In the wake of the case, Mr and Mrs Duffy helped to organise a petition to abolish Scotland's `not proven' verdict. It attracted more than 60,000 signatures.

The Duffys could not let the case rest. They knew that the powerful, pony-tailed Mr Auld is a year older than Amanda. He went to the same school. He lived with his parents a mile away from her. The two knew each other. On the night she was killed, Amanda was celebrat- ing winning a place in a local college of higher education with some girlfriends. As they walked to a taxi rank, Amanda was approached by Francis Auld. The friends left the two talking, expect- ing Amanda to rejoin them in the queue for a cab.

When interviewed by the police about what had happened next, Mr Auld gave contradictory and incomplete answers. No witnesses, for example, saw him return on the route he said he took, although there were plenty who would have noticed him had he fol- lowed the path he claimed. He lied to the police about what he had been wearing. Tests showed that, despite having been thoroughly washed very recently, his wrist- watch and Walkman were both splattered with tiny spots of blood — though the droplets were too small to test for type. Dr James Govan, a forensic scientist, said that 20 brown hairs found next to Amanda's body were the same length and colour as Mr Auld's, and microscopically similar. He pronounced the match one of the best he had ever seen, although in the absence of a DNA test — the police did not even bother to commission one, perhaps confident of their evidence — identificatiqn could not be completely certain.

But the most apparently damning evi- dence of all against Mr Auld was a cres- cent-shaped bite mark on Amanda's right breast. Auld admitted he was responsible for it. He said that it was a lovebite he had given her in a brief petting session which had occurred in a shop window just after they met, and just before she disappeared — Mr Auld claimed she had gone off with a man called Mark. 'Mark' was never traced or identified. None of Amanda's friends had seen or heard of him. As to the `lovebite' which Mr Auld admitted he had inflicted on Amanda, two doctors — one a professor of pathology, one a hospital con- sultant — swore on oath that that bite was the result of an act of the most vicious vio- lence. It was impossible that it had been `made in amorous circumstances'. From the depth of the teeth marks, the pain it caused would have been 'excruciating'. Fur- thermore, the pathologist pointed out that if what Mr Auld claimed had happened was true, Amanda would have had to put her bra back on before walking off with `Mark'. Her bra would have been stained with blood from the lovebite'. It was not. There was no blood anywhere on it.

Having heard that evidence, the jury declined to find Mr Auld guilty. Their rea- soning will remain a mystery forever, not because it is inherently mysterious, but because the 1981 Contempt of Court Act makes it an offence to scrutinise the way jurors come to their decisions. Judges and law-makers apparently fear any research would undermine faith in the system which indicates how much faith judges and law-makers have in it. The police routinely claim that the biggest problem with today's jurors is that they are biased against the police.

Mr Donald Findlay, Mr Auld's barrister, is contemptuous of that claim. He accepts that the public's opinion of the police has slumped, but that is 'entirely the police's own doing'. The well-publicised miscar- riages of justice over the past 20 years have been enough to convince members of the public that police evidence is not to be taken at face value: police can lie and fabri- cate as effectively as any criminal. Mr Findlay's successful defence of Mr Auld was built around a decision to keep him out of the witness box. The standard lawyer's argument for that strategy is that to allow a defendant to give evidence is to give credence to an inadequate prosecu- tion's case against him. So the jury heard nothing from Mr Auld except recordings of his interviews by the police. Just as importantly, in his closing speech, Mr Findlay also expressed the fear that has haunted every juror since the Birmingham Six and the Guildford Four were freed: the fear of being responsible for the conviction of an innocent man. 'You and you alone are the most important people in this case,' he told the jury closing his defence of Fran- cis Auld, 'because you alone stand between the accused and a miscarriage of justice . . . '

Mr Findlay was of course pleased with the jury's decision to vote for a not proven verdict. He is dismissive of the idea that that verdict amounts to less than a full acceptance of Mr Auld's innocence. 'Only the legally uneducated think a criminal trial is about guilt or innocence,' he explained when interviewed last week. 'Guilt or inno- cence doesn't feature anywhere . . . What a criminal trial is about is whether the Crown has proved the allegation it makes.' But could not a skilled advocate neverthe- less exploit the jury's fear of finding the wrong man guilty? 'Absolutely right,' Mr Findlay replied. 'What is wrong with that? Not guilty does not mean innocence . . . guilt and innocence are ethereal concepts known only to God.'

God will no doubt pass judgment on those found 'not guilty' by the courts. In the meantime, however, that verdict means that the accused is free to roam the streets. And if he is not innocent, it also means he ,is free to offend again. Mr and Mrs Duffy share Mr Findlay's belief that 'not proven' does not mean innocence, though for dif- ferent reasons. That belief was reinforced when Mr Auld appeared in court for a sec- ond time. Mr Auld was charged with mak- ing a series of abusive phone calls to friends who had broken off contact after his trial. He admitted saying to one female friend that, 'You thought Amanda was the last . . . well, you are next.' The court found him guilty of harassment. Taking his previ- ous good character and unblemished record into account, it sentenced him to 240 hours of community service.

What were Mr and Mrs Duffy to do now? What can anybody do if not satisfied with a verdict? Many people as convinced as they are of the identity of their daugh- ter's killer would think the primary chal- lenge was how to organise an act of violent vengeance. But the Duffys are not vigi- lantes. They are . strong and sincere Catholics. Their conception of justice is not bloody revenge. 'We just want to see a court name Francis Auld as responsible for our daughter's death. That's all.'

Because Mr Auld was prosecuted by the Crown for the murder and the case was `not proven', there is only one alternative: an action in a civil court. Mr and Mrs Duffy are suing Mr Auld for the 'loss of society' of their daughter. They are required by law to name the amount of compensation they are seeking. 'We've asked for £50,000, but the money is not the point,' explains Mrs Duffy. 'We know we won't get it even if we win.' But the money is not the point.

Though a civil court has a lower standard of proof than one used in a criminal pro- ceedings — the standard being merely the balance of probabilities, rather than the more severe requirement of proof beyond reasonable doubt — it will be extraordinar- ily difficult for the Duffys to win their suit. When Mrs Linda Griffiths won £50,000 in damages last week after successfully suing Michael Williams, her former employer, for rape, she joined the tiny handful of plaintiffs who have succeeded in gaining redress for a criminal offence through the civil courts. Most do not try, and most of those who do Even Mrs Griffiths's award is not secure: Mr Williams is appeal- ing, and may win in a higher court. That has happened before. In 1988 a woman was awarded £25,000 in damages against Ken- neth Cain, a physiotherapist she claimed had raped her. At the time, it was only the second successful suit of its kind this centu- ry. The Court of Appeal ended that claim to fame when it quashed the original rul- ing, saying that the hearing on which it was based had been unfair.

The Duffys face a further obstacle in that those two cases were brought after the Crown had decided not to prosecute the alleged rapists. It was not that they were tried• and acquitted; they were not tried at all. That at least left open the possibility that a jury would have returned a guilty verdict. The Duffys will be fighting a man who can point to a decision of 'not proven'. There is only one precedent for what the Duffys are trying to achieve, and even in that case, the parallel is not exact. In 1991, Mrs Gail Halford won an action for dam- ages against Michael Brookes and his step- son Fitzroy. She claimed they had murdered her daughter. Fitzroy Brookes had been tried and acquitted of stabbing Mrs Halford's daughter 41 times. He gave evidence in the civil suit against his stepfa- ther. Though both of them were named in the suit, only the father was judged to be liable. After 13 years of relentless struggle, Gail Halford at last saw the man who killed her daughter condemned for it in court. The creaking machinery of the civil courts is not a firm platform from which to pursue the man they believe to be Amanda's mur- derer, but it is the only chance Mr and Mrs Duffy have.

`Wrongful convictions can be appealed against,' Mr Duffy stresses. 'But for the vic- tims and their families who feel there has been a wrongful acquittal there is no such appeal.' It is not easy to explain to him why justice requires a system based on the idea that it is better that ten guilty men go free than one innocent man be punished. For, in theory, it is at least arguable that the consequences of acquitting a guilty man are at least as bad, if not worse, than pun- ishing an innocent one. An innocent man who is imprisoned may be released. Noth- ing will return life to the victim of a mur- derer who has been acquitted.

Philosophers and lawyers are fond of pointing out that it is not the legal system's fault if a man who is acquitted goes on to commit crimes. The criminal's actions are his responsibility, not the courts. When a court condemns an innocent man, on the other hand, it implicates the entire legal system directly in injustice. That outcome must be avoided, almost at any cost. The emphasis on preserving the integrity of the legal system is extremely persuasive until you or your family believe yourselves to be victims of someone who is acquitted because of it.

Mr and Mrs Duffy have discovered for themselves how painful our legal system's commitment to its own integrity can be. They have lived for two years with lawyers who have told them not to be 'over-emo- tional', and they will have to cope with many more.

Whilst supporters of the Criminal Justice Act believe that some of its provisions will make it easier for jurors to reach guilty ver- dicts, no one is proposing to reform the jury system or to abolish the prohibition on double jeopardy — and for good reason. Both, however unfortunate their conse- quences, are better than the alternatives. That guarantees that the Duffys will not be the last people who feel they are victims of a system of justice which tilts too far in favour of the accused. Civil suits, with all their costs and disadvantages, will remain the only avenue of redress for people like Mr and Mrs Duffy. Francis Auld has 21 days to answer their writ. They await his response.

Previous page

Previous page