Not inclined to think well of mankind

Peter Quennell

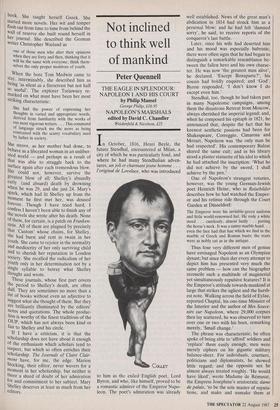

THE EAGLE IN SPLENDOUR: NAPOLEON I AND HIS COURT by Philip Manse'

George Philip, f16.95

NAPOLEON'S MARSHALS edited by David C. Chandler

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, f25

In October, 1816, Henri Beyle, the future Stendhal, encountered at Milan, a city of which he was particularly fond, and where he had many Stendhalian adven- tures, un joli el charmant jeune homme . . . l'original de Lovelace, who was introduced to him as the exiled English poet, Lord Byron, and who, like himself, proved to be a romantic admirer of the Emperor Napo- leon. The poet's admiration was already well established. News of the great man's abdication in 1814 had struck him as a personal blow; and he had felt 'damned sorry', he said, to receive reports of the conqueror's last battle.

Later, once his wife had deserted him and his mood was especially hubristic, there were often signs that he had begun to distinguish a remarkable resemblance be- tween the fallen hero and his own charac- ter. He was now 'the greatest man alive', he declared. `Except Bonaparte?', his cousin had boldly enquired; and `God', Byron responded, `I don't know I do except even him.' Stendhal, too, though he had taken part in many Napoleonic campaigns, among them the disastrous Retreat from Moscow, always cherished the imperial legend; and, when he composed his epitaph in 1821, he announced that, despite the fact that his keenest aesthetic passions had been for Shakespeare, Correggio, Cimarosa and Mozart, Napoleon was `the only man he had respected'. His contemporary Balzac shared the same cult; and in his library stood a plaster statuette of his idol to which he had attached the inscription: `What he did not achieve by the sword, I shall achieve by the pen.'

One of Napoleon's strangest votaries, however, was the young German-Jewish poet Heinrich Heine, who in Reisebilder describes how he had watched the Emper- or and his retinue ride through the Court Garden at Dusseldorf:

The Emperor wore his invisible-green uniform and little world-renowned hat. He rode a white steed . . . carelessly, almost lazily . . . patting the horse's neck. it was a sunny marble hand.. . even the face had that hue which we find in the marble of Greek and Roman busts; the traits were as nobly cut as in the antique.

Thus four very different men of genius have envisaged Napoleon as an Olympian dynast; but since their day every attempt to depict him has presented very much the same problem — how can the biographer reconcile such a multitude of magisterial yet simultaneously repulsive features? It is the Emperor's attitude towards mankind at large that strikes the ugliest and the harsh- est note. Walking across the field of Eylau, reported Chaptal, his one-time Minister of the Interior and the author of Mes Souve- nirs sur Napoleon, where 29,000 corpses then lay scattered, he was observed to turn over one or two with his boot, remarking merely, `Small change.'

The phrase was characteristic; he often spoke of being able to 'afford' soldiers and `replace' them easily enough; men were merely ciphers on his gigantic military balance-sheet. For individuals, courtiers, politicians and diplomatists, he showed little regard; and the opposite sex he almost always treated roughly. 'He would have liked', wrote Madame de Remusat, the Empress Josephine's aristocratic dame de palais, 'to be the sole master of reputa- tions, and make and unmake them at pleasure. He would compromise a man or tarnish a woman at a word . . .' Nor did he suffer from remorse and regrets. On St Helena, when an attendant ventured to pronounce the name of the duc d'Enghien the gallant young man, last of the Conde line, whom he had had kidnapped and judicially assassinated — 'not a crime so much as a major mistake', Talleyrand muttered in the background — the Emper- or crossly brushed the subject aside: `What, the Enghien affair? Pooh! What is one man after all?'

The Eagle in Splendour by Philip Mansel and Napoleon's Marshals, a collection of essays edited by David Chandler, cover between them nearly the whole extent of the Napoleonic legend. Philip Mansel deals especially with his courts. Determined to replace the Ancien Regime by establishing an equally glorious substitute, Napoleon I, like the emperor who inherited his name, 'used splendour as a weapon'. He was a great stage manager; no other European court was more ceremonious, more luxu- rious, more magnificently uniformed or richly jewelled. Napoleon adopted some of the Bourbon customs, for instance the Royal Hunt at Compiegne, where Carle Vernet depicted him shooting the cornered stag himself, but carried them to more picturesque extremes.

The Emperor had a modern understand- ing of the value of publicity. Great fame, he explained to his school-friend Louis de Bourrienne, was primarily 'a great noise. The more one makes, the further it carries. Laws, institutions, monuments all have their day. But noise remains and resounds in other ages.' My power derives from glory', he told other friends, 'and would collapse if I failed to base it on more glory and fresh victories . . . Conquest alone can maintain me.' These theories were found- ed on a solid cynicism; Napoleon, Bour- rienne decided, was 'not inclined to think well of mankind'; there were two powerful levers that moved the human race — fear and self-interest. 'Friendship is only a word', Bourrienne once heard him add.

None of his 26 marshals, who served him so energetically, and, as a rule, so efficient- ly, can be counted as a true friend; and some, at the end, would join the Bourbons. Both these books are well illustrated; and The Eagle in Splendour includes 'one of the last European representations of a monarch as a god', painted for his palace at Milan, which shows Napoleon in the pose of Jupiter, 'supported by Justice, Force, Prudence and Temperance'. Napoleon's Marshals, too, besides some vigorous biog- raphical sketches by 27 different hands, contains some very fine pictures. It has one disadvantage, however; the volume weighs some three-and-a-half pounds; and each essay is prefaced by a full-page portrait, which is overprinted not only by a subtitle but, a little further down, by the marshal's name, sometimes just across or very near his nose.

Previous page

Previous page