Arts

A painter of country ways

Simon Blow

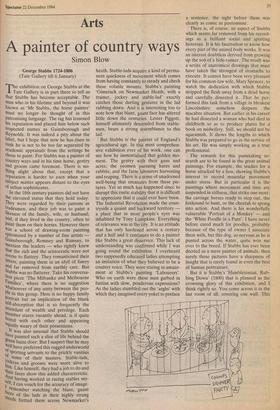

George Stubbs 1724-1806 (Tate Gallery till 6 January)

The exhibition on George Stubbs at the Tate Gallery is in part there to tell us that Stubbs has become acceptable. The man who in his lifetime and beyond it was known as 'Mr Stubbs, the horse painter' Must no longer be thought of in this Patronising language. The tag has lessened his reputation and placed him below such respected names as Gainsborough and Reynolds. It was indeed a pity about the label, but I hope that now he has risen in rank he is not to be too far separated by academic appraisals from the settings he chose to paint. For Stubbs was a painter of Country ways and in his time horse, gentry and groom came foremost. There is no- thing slight about that, except that a reputation is harder to earn when your subject matter appears distant to the eyes of urban sophisticates.

In the 18th century painters did not have the elevated status that they hold today. They were regarded by their patrons as tradesmen, and their job was to paint a likeness of the family, wife, or husband; and, if they lived in the country, often to Paint them on their horses. However there Was a school of drawing-room painting epitomised by a number of fine artists — Gainsborough, Romney and Ramsay, to mention the leaders — who rightly knew that the rich and the aristocratic were not averse to flattery. They romanticised their sitters, painting them in an idyll of finery and far removed from earthly care. But Stubbs was no flatterer. Take his conversa- tion piece The Milbanke and Melbourne Families', where there is no suggestion Whatsoever of any unity between the peo- Ple in this group. Here is no happy family Portrait but an implication of the blank self-absorption that is so frequently the attendant of wealth and privilege. Each member stares vacantly ahead, is if quite bored with each other and appearing equally weary of their possessions. It was also unusual that Stubbs should have painted such a slice of life behind the green baize door. But I suspect that he may Well have preferred this rugged underworld of sporting servants to the prickly vanities °f some of their masters. Stable-lads, 1.113.ekeys and grooms were more alive to their1111. Like himself, they had a job to do and faces show this added characteristic. And having worked in racing stables my- felt., I can vouch for the accuracy of image. remember watching the blunt, gaunt faces of the lads as their highly strung steeds fretted them across Newmarket's heath. Stable-lads acquire a kind of perma- nent quickness of movement which comes from having constantly to steady and check these volatile mounts. Stubbs's painting `Gimcrack on Newmarket Heath, with a trainer, jockey and stable-lad' exactly catches those darting gestures in the lad rubbing down. And it is interesting too to note how that blunt, gaunt face has altered little down the centuries. Lester Piggott, himself ultimately descended from stable- men, bears a strong resemblance to this lad.

But Stubbs is' the painter of England's agricultural age. In this most comprehen- sive exhibition ever of his work, one can see how he immortalised that golden mo- ment. The gentry with their guns and acres; the yeomen pursuing hares and rabbits; and the farm labourers harvesting and reaping. There is a sense of unadorned well-being that emanates from these pic- tures. Yet so much has happened since to disrupt this rustic stability that it is difficult to appreciate that it could ever have been. The Industrial Revolution made the coun- tryside a quaint and backward territory a place that in most people's eyes was inhabited by Tony Lumpkins. Everything of relevance was in the city. It is an attitude that has only hardened across a century and a half and it continues to do a painter like Stubbs a great disservice. This lack of understanding was confirmed while I was going round the exhibition. I overheard two supposedly educated ladies attempting an imitation of what they believed to be a country voice. They were staring in amaze- ment at Stubbs's painting 'Labourers'. Who on earth were these men garbed in fustian with slow, ponderous expressions? As the ladies stumbled out the 'arghs' with which they imagined every yokel to preface a sentence, the sight before them was clearly as comic as pantomime.

There is, of course, an aspect of Stubbs which seems far removed from his record- ings as a brilliant social and sporting historian. It is his fascination to know how every part of the animal body works. It was an interest doubtless derived from growing up the son of a hide-tanner. The result was a series of anatomical drawings that must have taken the strongest of stomachs to execute. It cannot have been very pleasant for his common-law wife, Mary Spencer, to watch the dedication with which Stubbs stripped the flesh away from a dead horse and carefully dissected it. That he per- formed this task from a village in bleakest Lincolnshire somehow deepens the macabre situation. But earlier in his career he had dissected a woman who had died in childbirth so as to produce plates for a book on midwifery. Still, we should not be squeamish. It shows the lengths to which Stubbs was prepared to go in the service of his art. He was simply working as a true professional.

The rewards for this painstaking re- search are to be found in the great animal paintings. For example, the studies for a horse attacked by a lion, showing Stubbs's interest to record muscular movement under stress. But in particular it is the paintings where movement and time are suspended in stillness, that strike one most: the carriage horses ready to step out, the foxhound to hunt, or the cheetah to spring into action. And there is his wonderfully vulnerable 'Portrait of a Monkey' — and the 'White Poodle in a Punt'. I have never before cared much for poodles, probably because of the type of owner I associate them with, but this dog, so nervous as he is punted across the water, quite won me over to the breed. If Stubbs has ever been decried as a mere painter of animals, then surely these pictures have a sharpness of insight that is rarely found in even the best of human portraiture.

But it is Stubbs's `Hambletonian, Rub- bing Down' (1800) that is planned as the crowning glory of this exhibition, and I think rightly so. You come across it in the last room of al , covering one wall. This life-size portrait of a racehorse exhausted from a four-mile match can be seen as a summing up on Stubbs's integrity. Painted in the last years of his life, it was contrary to what his patron had hoped for. Sir Henry Vane Tempest would have liked his horse done in the winner's enclosure, jockey up, amid the cheers of the crowd. But Stubbs saw it differently. He preferred the more truthful composition of the lad rubbing down the panting horse while the trainer holds him. He wanted to paint the toughness of racing as distinct from tran- sient glamour.

I am glad that this celebration of Stubbs has happened. Seeing his work gathered here is to be refreshingly reminded of a more settled society that was not plagued by the neurasthenia of the city. It was a largely contented world that never looked beyond itself. And after the sheer quality of the painting, it is this calm that Stubbs brings back to us. Those who still live in our countryside may find that this exist- ence has not quite gone; and fbr others, to learn through Stubbs that it was once possible, should be a solace.

Previous page

Previous page