Skinflint's City Diary

Try too hard to stop unemployment and the result could very easily be even greater unemployment. That is, if the aim is merely the shortterm policy governments seem incapable of resisting. Ministers appear to have a constitutional inability to let nationalised industries go their own way without forever nudging them here, stopping them dead there, examining them all the time, and countermanding somewhere else. (No I have not changed the subject — all will become clear.) This applies equally to both parties: Tom Boardman, the last Tory minister in charge of steel, would ring up the British Steel Corporation once or twice a week — well, very often anyway — to tell it what to do. And this from a Conservative minister with supposedly experience of industry.

Needless to say chairman Sir Monty Finniston did not enjoy being treated as a glorified office boy, and tension developed. Sir Monty is an independent-minded man near enough to retirement and with enough of a reputation in the steel industry (and an FRS) to speak his mind. But eventually he and the BSC management team evolved a long-term policy and a programme to close expensiveto run antiquated plants and replace them with new steelworks and modern equipment.

Then came the present government and stopped the whole thing dead. One minister has been touring the country talking to steelworkers and to people in the communities where the steelworks are. Worthy people doubtless, but perhaps not the most sophisticated in the strategic planning necessary for one of the world's largest steel companies. The avowed purpose was grass roots democracy.

The real reason however is probably partly the recurrent feeling of politicians and civil servants that God knows but they know better. But even more the cause was the great ministerial predilection for sacrificing long-term efficiency on the altar of short-term political expediency. Hence the not unnatural desire to keep down unemployment at a time when it is rising. But this has led to a decision to maintain uneconomic plant which will result in higher steel prices, hence a less competitive British industry, and hence eventual higher unemployment.

But don't take my word for it. The steel users, who have in the past not always been wholly on BSC's side are now asking the pertinent question of who is to pay for the additional costs of running old plant and delaying the paying for new equipment. In other words who pays for the higher maintenance, running costs, and overmanning of the present open hearth steelmaking — the costs being possibly several hundred millions of pounds? And who pays for the higher costs of new plant or for the higher imports when BSC fails to compete?

The decision may have been taken in all honesty on the view that ministers knew better than BSC what the community needs and they can tell whether the country can absorb 40,000 extra unemployed over the next five years. But Of Course as everyone else can see it was wrong. The main

problem of this is not only that it totally demoralises nationalised industries who wonder why in heaven's name they are set financial targets, and whether it is worth even attempting planning. But there is also the constant extra problem for the rest of industry never knowing what the criteria will be for their suppliers and unable to forecast either quantity or price.

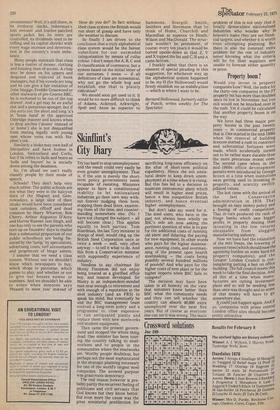

Property boom?

Would you invest in property companies in ow? Well, the index for the thirty-one companies in the FT property list has more than doubled since its low in November, but you still would not be knocked over in the rush. Yet it could be calculated that another property boom is on the way.

We have had three major property booms in the past twenty years — in commercial property that is. One started in the mid-1950s when the removal of building licences started a rush to construct and substantial fortunes were made, which incidentally turned out to be rather more durable than the more precarious recent ones. The second came when in the mid-1960s office development permits were introduced by George Brown at a time when institutions were getting used to investing in property, and scarcity swiftly inflated values. The last came with the arrival of the last Conservative administration in 1970. That brought an easy money policy and a freeing of credit competition. That in turn produced the rash of fringe banks which saw bigger profits in property dealing than investing in the low returns obtainable from sluggish manufacturing industry.

Now we have had the relaxation of the rent freeze, the lowering of interest rates (which should ease the agonising burden on some hard-hit property companies), and the Greater London Council is contemplating putting a ban on office building. The full council meets this week to take the final decision. And all this at a time when manufacturers are cutting investment plans and so will be needing less than once was thought and so some of that money will have to go somewhere else.

It could just happen again. And if so, companies with prime central London office sites should become pretty attractive.

Previous page

Previous page