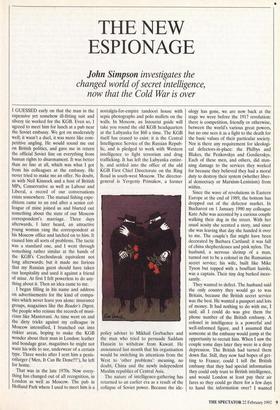

THE NEW ESPIONAGE

John Simpson investigates the

changed world of secret intelligence, now that the Cold War is over

I GUESSED early on that the man in the expensive yet somehow ill-fitting suit and silvery tie worked for the KGB. Even so, I agreed to meet him for lunch at a pub near the Soviet embassy. We got on moderately well; it wasn't a duel, it was more like com- petitive angling. He would sound me out on British politics, and gave me in return the official Soviet line on everything from human rights to disarmament. It was better than no line at all, which was what I got from his colleagues at the embassy. He never tried to make me an offer. No doubt, as with Neil Kinnock and a host of British MPs, Conservative as well as Labour and Liberal, a record of our conversations exists somewhere. The mutual fishing expe- ditions came to an end after a senior col- league of mine joined us and blurted out something about the state of our Moscow correspondent's marriage. Three days afterwards, I later heard, an attractive young woman rang the correspondent at his Moscow office and latched on to him. It caused him all sorts of problems. The tactic was a standard one, and I went through something rather similar at the hands of the KGB's Czechoslavak equivalent not long afterwards; but it made me furious that my Russian guest should have taken our hospitality and used it against a friend of mine. At first I felt powerless to do any- thing about it. Then an idea came to me.

I began filling in his name and address on advertisements for the kind of compa- nies which never leave you alone: insurance groups, magazines like the Reader's Digest, the people who reissue the records of musi- cians like Mantovani. As time went on and the dirty tricks against my colleague in Moscow intensified, I branched out into riskier areas, hoping to make the KGB wonder about their man in London: leather and bondage gear, magazines he might not want his wife to see, underwear of a certain type. Three weeks after I sent him a penis- enlarger ('Men, It Can Be Done!!!'), he left for home.

That was in the late 1970s. Now every- thing has changed out of all recognition, in London as well as Moscow. The pub in Holland Park where I used to meet him is a nostalgia-for-empire tandoori house with sepia photographs and polo mallets on the walls. In Moscow, an Intourist guide will take you round the old KGB headquarters at the Lubyanka for $60 a time. The KGB itself has ceased to exist: it is the Central Intelligence Service of the Russian Repub- lic, and is pledged to work with Western intelligence to fight terrorism and drug trafficking. It has left the Lubyanka entire- ly, and settled into the office of the old KGB First Chief Directorate on the Ring Road in south-west Moscow. The director- general is Yevgeniy Primakov, a former policy adviser to Mikhail •Gorbachev and the man who tried to persuade Saddam Hussein to withdraw from Kuwait. He announced last month that his organisation would be switching its attentions from the West to 'other problems': meaning, no doubt, China and the newly independent Muslim republics of Central Asia.

The nature of intelligence-gathering has returned to an earlier era as a result of the collapse of Soviet power. Because the ide- ology has gone, we are now back at the stage we were before the 1917 revolution: there is competition, friendly or otherwise, between the world's various great powers, but no one sees it as a fight to the death for the basic values of their particular society. Nor is there any requirement for ideologi- cal defectors-in-place: the P.hilbys and Blakes, the Penkovskys and Gordievskys. Each of these men, and others, did stun- ning damage to the services they worked for because they believed they had a moral duty to destroy their system (whether liber- al democracy or Marxism-Leninism) from within.

Since the wave of revolutions in Eastern Europe at the end of 1989, the bottom has dropped out of the defector market. In Bucharest on 1 January 1990 my colleague Kate Adie was accosted by a curious couple walking their dog in the street. With her usual acuity she scented a story, and since she was leaving that day she handed it over to me. The couple's flat might have been decorated by Barbara Cartland: it was full of china shepherdesses and pink nylon. The husband, a nervous shrimp of a man, turned out to be a colonel in the Rumanian secret service; his wife, built like Mike Tyson but topped with a bouffant hairdo, was a captain. Their tiny dog barked inces- santly.

They wanted to defect. The husband said the only country they would go to was Britain, because the British secret service was the best. He wanted a passport and lots of money. It had nothing to do with me, I said; all I could do was give them the phone number of the British embassy. A colonel in intelligence is a powerful and well-informed figure, and I assumed that someone at the embassy would jump at the opportunity to recruit him. When I saw the couple some days later they were in a deep depression. The British had turned them down flat. Still, they now had hopes of get- ting to France; could I tell the British embassy that they had special information they could only trust to British intelligence, and would London at least pay their air fares so they could go there for a few days to hand the information over? I wanted nothing to do with the whole business, but I needed to interview them for television and this was their condition for agreeing. I made another call. No can do, said the man at the embassy. Back to Barbara Cartland and the yapping dog: if they paid their own way to London, might British intelligence just see them for a couple of hours? I tried again. The French can talk to them, said the embassy man implacably. By the begin- ning of 1990, every secret service in the Eastern bloc was leaking would-be defec- tors at the highest possible levels; and with the collapse of Soviet power the only infor- mation the best of them had to offer was of no more than historical interest.

The logic of the changed relationship between what we used to call East and West means that nowadays, if you are a Russian secret intelligence man in London, you will probably be less interested in try- ing to recruit your agents in the Ministry of Defence than in, say, the Treasury or the Bank of England. You want agents of influ- ence who will assist your economic inter- ests; it is a matter of urgency to receive advance warning of changes in internation- al finance, rather than (as in the old days) of possible pre-emptive nuclear strikes. It would be useful to the Russians to know who, at the level of G-7, the IMF or the World Bank, are their real friends and who is holding up their chances of greater aid, and what can be done about it. From now on, Karla's spymasters at Moscow Centre will need degrees in international finance, and James Bond will have to turn char- tered accountant.

No doubt, too, the range of our own interests will broaden. Peter Wright in his paranoid book Spycatcher described how MI5 bugged the French embassy for infor- mation about France's line in Common Market negotiations. Nowadays, I have been authoritatively assured, the links between us and our European partners are so close that no such means are required. On the other hand, John Major's success in anticipating the ultimate positions of France and Germany at the Maastricht summit last December was so considerable that a flicker of speculation crossed my mind at the time. Could it be ... ? No, sure- ly not. Yet setting Europe aside, the busi- ness of finding out other countries' intentions and trying to influence them will go on at least as strongly as before; perhaps more so. At a time when we are cutting back on our defence capability, the secret vote appears to be holding up, and perhaps even growing. Indeed, the more we, the Americans and the Russians reduce our armed forces, the better information we require; and although the KGB is being heavily reduced, the GRU — Soviet and, presumably nowadays Russian, military intelligence — remain unpruned, largely unnoticed, and pretty effective.

Nevertheless, the old paranoia at the heart of intelligence work, the fear of imminent and mutually assured destruc-

tion, is over. Dr Christopher Andrew, the leading academic in the field, says that between 1981 and 1984 the KGB became convinced that President Reagan and his Nato allies were going to attack the Soviet Union without warning. As a result, every KGB station around the world had to report back to Moscow Centre once a fort- night on an extraordinary checklist of indi- cators; in London, Dr Andrew says, they had to report on the level of blood donors and on how many lights were burning at night in the Ministry of Defence. Accord- ing to the last minister in charge of the KGB before it was closed down, Vadim Bakatin, the fortnightly checks went on to the very end.

Western intelligence services will no doubt find themselves continuing to target Russian spies and vice versa; but the old competition in the Third World is over, and no one will be. able to excuse the main- taining of some savage killer in power merely because it stops the other side from getting a foothold in the country he rules. Each intelligence organisation will obvious- ly play to its old strengths: Moscow still no doubt receives better information from Libya and Iraq than Britain or the United States do. But information is a valuable commodity, and it will be traded to Rus- sia's best advantage; that will be another way by which Moscow can demonstrate its value as an international partner, which the West should assist to the best of its ability.

'For the British intelligence services, the main tasks now are to combat nuclear pro- liferation, the spread of chemical weapons, international terrorism and drug traffick- ing. The break-up of the Soviet empire and the sudden availability of nuclear and bio- logical weapons mean that most Western governments need to extend the range of their intelligence services. The old balance- sheet by which the Secret Intelligence Ser- vice (its correct name, MI6, though often used, is not the formal title) directed a third of its resources towards the Soviet bloc and the remainder to the rest of the world can now perhaps be redrawn a little.

The SIS has always done its best to keep a presence in as many countries as possible, regardless of the old ideological divisions. Like a news agency or a newspaper, the quality of its reporting is the better for it, and the flow of useful information which `Best served at room temperature . . can be exchanged with other governments is of real value, even in unlikely areas. Britain's links with Iran first began to improve in the mid-1980s, when a Soviet defector gave the SIS details of the extent to which the KGB had infiltrated the Irani- an government. The SIS passed it on. Now it is reasonable to expect that the SIS will look for ways of gaining credit with the new ex-Soviet republics in Central Asia by pass- ing on to them anything it hears about Ira- nian intentions towards them. It may be that a new Great Game is beginning in the region where it flourished 100 years ago; if so, the SIS is in a good position to be a player once again.

Recruitment to the SIS is taking a new direction. From the Baltic states to the Pamirs, there are new countries to report on. That requires fresh blood: men and women with the ability to speak unfamiliar languages. For years, the SIS is said to have been reluctant to recruit too heavily at British universities, and preferred to look to the armed forces. Now, by all accounts, academics with a past in intelligence are more active in talent-spotting again among the students. If you have to teach someone Armenian or the Turkish of Azerbaijan you have to start them early. The politics of the new recruits may be less important than they were in the old days, and people who do not come from a white, Anglo-Saxon background could have a distinct advan- tage.

The Security Service, which is usually called MI5, has gone through a more diffi- cult time. In 1989 its director-general, Sir Patrick Walker, commissioned a private personnel firm (rumoured to be Saxon Bamfylde) to examine its recruitment poli- cy. It seems to have been needed: the ser- vice suffered a big setback at the time of the Gulf war, when it arrested a number of law-abiding Iraqis and Palestinians, several of whom had been courageously and open- ly critical of Saddam Hussein, on suspicion that they were planning to carry out terror- ist attacks. Much of the information the Security Service was acting on turned out to be seriously inaccurate.

Nowadays, the service is beginning to lose a little of its ludicrous, and disturbing, secrecy. Its official existence has been pub- licly recognised. On 25 February it will have a new director-general, Mrs Stella Rimington, and it will no longer be true that its address in Gower Street, well- known to the KGB, cannot be published in Britain. Soon, indeed, it will take over its new and refurbished headquarters at Thames House, a large Grade 2 listed building on Millbank, which has been extended without planning permission and at a cost of £100 million to provide office space for 2,300.

Within sight of Thames House, on the other side of the river at Vauxhall Bridge, a strange erection is going up with approxi- mately 12 storeys (it is, rather suitably, dif- ficult to count them), green sections that

look like Lego implants, and the obligatory columns and arches with which British architects have responded to the com- plaints of the Prince of Wales. Reports that the Security Service and the Secret Intelli- gence Service are to share the same head- quarters are untrue: the building at Vauxhall Cross, reminiscent of the palace Nicolae Ceausescu built for himself in Bucharest, will be home to the SIS alone; and it is possible that even before it makes the move from its 1960s tower near North Lambeth tube station, Century House (which it is at present a breach of the Offi- cial Secrets Act to name), the existence of the service will at last be recognised pub- licly. It will no longer be necessary to trawl through Who's Who to work out that its director-general is Sir Colin McColl. The expectation is that the next government, whether Labour or Conservative, will end the old absurdity by which, virtually alone among democracies, Britain has pretended that it neither spies on foreigners nor on its own citizens.

The British love secrecy: we have, after all, so much of it in our public life. From the outward signs, however, it looks as though the SIS, after suffering so heavily from the betrayals of the past, ended the Cold War well ahead of all its European competitors, and at least on a par with the CIA, if not actually better. The fact that the SIS had the KGB station chief in Lon- don and possible future head of operations world-wide on its books was a major suc- cess; so was spiriting him out of Russia when he came under suspicion. It is believed, on good authority, that the SIS had other senior agents within the KGB and the Soviet structure whose names would rank close to that of Oleg Gordievsky. Intelligence, like broadcasting, seems to be something the British are still good at.

Maybe there is an occasional twinge of nostalgia for the old days; and indeed not everything has changed. There are thought to be around 40 full-time KGB operatives left in London. Igor Nikulin, a member of the Russian parliamentary commission on law enforcement, said last month that the government did not have enough money to bring back all the KGB agents who were stationed abroad. MI5 still carries out surveillance of the Russian embassy, and at least until recently Russian 'dry-cleaning' teams were still heading out of the embassy building in some numbers to decoy the watchers and mislead them about their true destination. Perhaps they were just going to have lunch at the old upgraded pub in Hol- land Park; perhaps they file their reports to the man whom I psed to meet there. As for him, I like to visualise him answering the door in his Moscow flat even now and find-

ing a Pearl Assurance salesman waiting patiently to explain some new plan to him.

And as he stands in his doorway, perhaps — if my parting gift was of value — a secret smile plays around his lips.

Previous page

Previous page