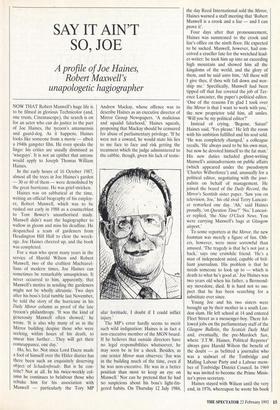

SAY IT AIN'T SO, JOE

A profile of Joe Haines, Robert Maxwell's unapologetic hagiographer

NOW THAT Robert Maxwell's huge life is to be filmed in glorious Technicolor (and, one trusts, Cinemascope), the search is on for an actor who can do justice to the part of Joe Haines, the tycoon's amanuensis and guard-dog. As it happens, Haines looks like someone from a movie — albeit a 1940s gangster film. He even speaks the lingo: his critics are usually dismissed as `wiseguys'. It is not an epithet that anyone would apply to Joseph Thomas William Haines.

In the early hours of 16 October 1987, almost all the trees in Joe Haines's garden — 30 or 40 of them — were demolished by the great hurricane. He was grief-stricken.

Haines was on sabbatical at the time, writing an official biography of his employ- er, Robert Maxwell, which was to be rushed out early in 1988 as a counterblast to Tom Bower's unauthorised study. Maxwell didn't want the hagiographer to wallow in gloom and miss his deadline. He despatched a team of gardeners from Headington Hill Hall to clear the wreck- age. Joe Haines cheered up, and the book was completed.

For a man who spent many years in the service of Harold Wilson and Robert Maxwell, two of the craftiest Machiavel- lians of modern times, Joe Haines can sometimes be remarkably unsuspicious. It never occurred to him, apparently, that Maxwell's motive in sending the gardeners might not be wholly altruistic. Two days after his boss's fatal tumble last November, he told the story of the hurricane in his Daily Mirror column as proof of the late tycoon's philanthropy. 'It was the kind of generosity Maxwell often showed,' he wrote. 'It is also why many of us in the Mirror building despise those who were seeking, within hours of his death, to smear him further ...They will get their comeuppance, one day.'

Ho, ho, ho. Not since Lord Dacre made a fool of himself over the Hitler diaries has there been such an exquisitely deserving

object of Schadenfreude. But is he con- trite? Not at all. In his twice-weekly col- umn he continues to belabour those who rebuke him for his association with Maxwell — particularly the Tory MP

Andrew Mackay, whose offence was to describe Haines as an executive director of Mirror Group Newspapers. 'A malicious and squalid falsehood,' Haines squeals, proposing that Mackay should be censured for abuse of parliamentary privilege. 'If he were not a coward, he would state his lies to me face to face and risk getting the treatment which the judge administered to the cabbie, though, given his lack of testic- ular fortitude, I doubt if I could inflict injury.'

The MP's error hardly seems to merit such wild indignation: Haines is in fact a non-executive member of the MGN board. If he believes that outside directors have no legal responsibilities whatsoever, he may soon be in for a shock. Besides, as one senior Mirror man observes: `Joe was in the building much of the time, even if he was non-executive. He was in a better position than most to keep an eye on Maxwell.' Nor can he pretend that he had no suspicions about his boss's light-fin- gered habits. On Thursday 12 July 1984, the day Reed International sold the Mirror, Haines warned a staff meeting that 'Robert Maxwell is a crook and a liar — and I can prove it'.

Four days after that pronouncement, Haines was summoned to the crook and liar's office on the ninth floor. He expected to be sacked. Maxwell, however, had con- ceived a crueller fate for the wretched lead- er-writer: he took him up into an exceeding high mountain and showed him all the kingdoms of the world, and the glory of them, and he said unto him, 'All these will I give thee, if thou wilt fall down and wor- ship me.' Specifically, Maxwell had been tipped off that Joe coveted the job of Ter- ence Lancaster, the paper's political editor. `One of the reasons I'm glad I took over the Mirror is that I want to work with you,' the new proprietor told him, all smiles. `Will you be my political editor?'

Instead of crying, 'Begone, • Satan!' Haines said, 'Yes please.' He left the room with his ambition fulfilled and his soul sold. `He was completely changed,' a colleague recalls. 'He always used to be his own man, but now he devoted himself to the fat man.' His new duties included ghost-writing Maxwell's animadversions on public affairs (which appeared under the pseudonym `Charles Wilberforce') and, unusually for a political editor, negotiating with the jour- nalists on behalf of management. He joined the board of the Daily Record, the Mirror's Scottish sister paper. 'Saw you on television, Joe,' his old rival Terry Lancast- er remarked one day. `Ah,' said Haines proudly, 'on Question Time?' No,' Lancast- er replied, 'the Nine O'Clock News. You were carrying Maxwell's bags at Glasgow airport.'

To some reporters at the Mirror, the new footman was merely a figure of fun. Oth- ers, however, were more sorrowful than amused. 'The tragedy is that he's not just a hack,' says one erstwhile friend. 'He's a man of independent mind, capable of bril- liant journalism. His problem is that he needs someone to look up to — which is death to what he's good at.' Joe Haines was two years old when his father, a Bermond- sey stevedore, died. It is hard not to sus- pect that he has been searching for a substitute ever since.

Young Joe and his two sisters were brought up by their mother in a south Lon- don slum. He left school at 14 and entered Fleet Street as a messenger-boy. There fol- lowed jobs on the parliamentary staff of the

Glasgow Bulletin, the Scottish Daily Mail and, eventually, the pre-Murdoch Sun, where 1.T.W. Haines, Political Reporter' always gave Harold Wilson the benefit of

the doubt — as befitted a journalist who was a stalwart of the Tonbridge and Mailing Labour Party and a Labour mem- ber of Tonbridge District Council. In 1969 he was invited to become the Prime Minis- ter's press secretary.

Haines stayed with Wilson until the very end, in 1976, whereupon he wrote his book

The Politics of Power. It was a devastating account of the impotence of Wilson's gov- ernment and the sleaziness of his entourage — which nevertheless managed

somehow to absolve the PM himself of blame. The main villain of the piece was Marcia Williams, Lady Falkender, who was revealed to have drawn up the infamous resignation honours list on her lavender writing paper. (Joe himself. as surprisingly few people know, refused a knighthood from Wilson. He is still enough of a class warrior to despise 'baubles'.)

The Politics of Power was serialised in the Daily Mirror, and its author was hauled

on board as a leader-writer soon after- wards. The poor orphan boy was not afraid to espouse lonely causes. It was he who

persuaded the Mirror to advocate the with- drawal of British troops from Northern Ireland in the late 1970s; in 1982, he wrote a series of magnificently furious editorials condemning the Falklands war.

But then Robert Maxwell arrived, and the politics of power beckoned once more.

Having become a member of the chair- man's 'Cabinet', Haines brought into it friends such as Bernard (now Lord) Donoughue and Helen Liddell, the former general secretary of the Scottish Labour Party. Janet Hewlett-Davies, Haines's old deputy from Downing Street, was hired as Maxwell's Director of Public Relations.

Lord Donoughue's involvement is of particular interest. He is one of Joe Haines's closest friends: they worked

together in Harold Wilson's office in the mid-1970s, and The Politics of Power gives

ample evidence of their harmonious part- nership (`Bernard Donoughue and I believed . . . Bernard Donoughue and I

spoke to the Prime Minister again . . . It

was clear to Bernard Donoughue and me . . .'). In 1988 he became executive vice-chairman of London and Bishopsgate,

the Maxwell firm which administered part of the Mirror pension fund. According to a

recent statement issued by his solicitors, Donoughue became aware in early 1991 that 'stocks had been lent from the portfo- lio without his knowledge'. In mid-July he `protested strongly to Mr Robert Maxwell' that this stock-lending had not ceased, and `following vigorous exchanges', resigned from London and Bishopsgate on 31 July.

'It beggars belief,' says one former exec- utive of Mirror Group Newspapers, 'that Bernard wouldn't have told Joe why he'd resigned from London and Bishopsgate.' Haines was a director of Mirror Group Newspapers; hig friend Donoughue would surely have wished to warn him of Maxwell's jiggery-pokery with the pension fund.

Yet, however belief-beggaring it may be, we must assume that Bernard did not tell Joe of his suspicions or, if he did, that Joe did not understand the implications. For on 11 December last year, interviewed for

the Today programme, Haines was asked by Peter Hobday whether he had suspect-

ed 'at any time' that Maxwell might stoop to fraud. 'No, I don't think anybody did,' he said. 'When all this broke, the other Sunday evening, it was a total and horrify- ing shock . . . I didn't know, I was flabber- . gasted and I never suspected it for a moment.'

Not even that moment, on Thursday, 12 July 1984, when he branded Robert Maxwell as a crook and a liar?

Previous page

Previous page