Heading to come

Teresa Waugh

THE CHAPEL ON FIRE by Michael Levey Jonathan Cape, £16.99, pp. 268 Autobiography must, of its very nature, be a tricky, tricky genre. There you are deciding to write about that most fascinating of all subjects — yourself. How do you set about doing it and what precisely inspires the urge? It may of course, if you are a world celebrity with a lurid sex life, be quite simply money or, if you are a politician, you may pompously wish 'to put the record straight' whilst by-passing an equally lurid sex life. In either case you probably want to be there, in the forefront, with the eyes of the world upon you. None of this applies to Michael Levey, but to this reviewer, whatev- er did inspire him to write The Chapel is on Fire, which he subtitles 'Recollections of Growing Up', remains a mystery. He did not for instance have a childhood such as the gruesome one described in Edmund Gosse's unforgettable, unputdownable Father and Son; neither, although his parents were strict Catholics, was their breed of Catholi- cism (designed, as Levey came to under- stand later, to prevent him thinking for himself) in any way comparable in its rep- ression to the cruel puritanism of Gosse's Plymouth Brethren.

As a boy, when asked what he wanted to be when he grew up, the young Michael Levey would answer 'Artist, actor, author'. This childish optimism and a first-class degree in English at Oxford have been fol- lowed by an immensely distinguished career, with, among other things, a list of eminent publications to his name, yet it is difficult to see exactly what it is about his childhood that should make it any more interesting than anyone else's. By page 190, when Levey is still only nine, the reader may begin to feel a sense of frustration, and long to know less about the child and more about the man, for the most moving part of the book is the Foreword in which Levey describes how his own rejection of Catholi- cism resulted in the painful estrangement between himself and his much loved father.

Unfortunately, so much about childhood is familiar — the loneliness, the embarrass- ment, the feeling different, the misunder- stood friendships, the playing in the woods, the inability to vault the 'horse', the pas- sionate feelings and the disappointments of early school days, so that, really to grip us, it has to be in some way exceptional, or exceptionally evoked. Michael Levey comes across as a pale, thin, clever little boy whose one claim to startling originality was not that he read Shakespeare precociously and was fascinated by history, nor that he liked dressing up and theatricals, certainly not that he found Blind Pew's tap-tapping the most frightening thing in Treasure Island, but that he collected toothbrush handles that he regarded as jewels. Even one of his favourite aunts, Senta, found nothing peculiar in his request that she fab- ricate wigs for him to wear as Charles II and Elizabeth I, his two preferred monar- chs. (Beginning already to break from the Catholic fold?) Levey dedicates his book suitably to his grandchildren who should be grateful for the trouble he has taken to draw such a pic- ture of their family and immediate ante- cedents. The family is of Irish descent, their real name being O'Shaughnessy which for some arcane and not fully explained reason, Levey's great-grandfather, the Dublin com- poser, saw fit to change. It was Levey's grandfather, wonderfully named Haydn Handel Levey, who settled in London where he married twice and produced some 15 children, one of whom was Michael's charming, humorous father, Otto.

Otto's childhood home was a substantial house in Brixton called Homeleigh. It fea- tures largely in the book as a welcoming haven presided over by a gaggle — or per- haps a charm — of maiden aunts who pro- vide the young Michael with a welcome contrast to his own home where his puritan- ical strait-laced mother, forever dressed in brown, casts something of a gloom. It is a sad moment when, just before the war, Homeleigh comes to be sold.

On reaching the end of this book, when Levey's army experiences suddenly seem very vivid and as the door to the National Gallery is first opened to him, the reader may wish to ask, what next? Perhaps Levey's intention in writing these recollec- tions was to get childhood out of the way before tackling the next bit.

. . Tall, dark hair, big blue eyes, and long legs all the way up to my neck . .

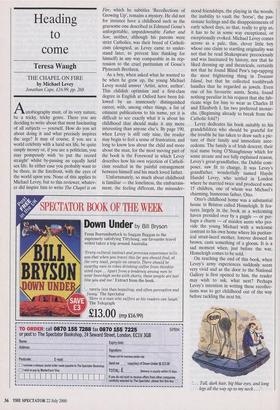

Previous page

Previous page