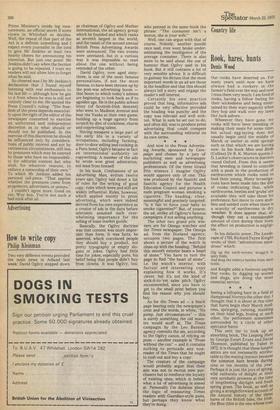

Advertising

How to write copy

Philip Kleinman

Two very different events provided the main news in Adland last week: David Ogilvy stepped down as chairman of Ogilvy and Mather International, the ad agency group which he founded and which ranks as seventh largest in the world; and the result of the second annual British Press Advertising Awards were announced. The two events were unrelated, but in a curious way it was impossible to read about the one without being reminded of the other.

David Ogilvy, now aged sixtythree, is one of the most famous personalities, if not the most famous, to have been thrown up by the post-war advertising boom — that boom to which today's admen are beginning to look back as if to agolden age. He is the public school limey (of Scottish-Irish descent) who went to Madison Avenue and beat the Yanks at their own game, building up a huge agency from scratch by dint of cockiness, charm and copywriting talent.

Having misspent a large part of his early life in a variety of occupations, including farming, door-to-door selling and cooking in a Paris hotel, Ogilvy became in fact an international authority on copywriting. A number of the ads he wrote won great admiration, not least from himself.

In his book, Confessions of an Advertising Man, written twelve years ago, Ogilvy laid down a list of rules for the writing of good copy, rules which were and still are widely influential. Rules, however; which applied mainly to press advertising, which were indeed derived from his own experience as a creator of ads in the days before television assumed such overwhelming importance for the selling of mass market goods.

Basically, the Ogilvy doctrine was that content was more important than form. It was facts, he asserted, which convinced people they should buy a product, not pretty typography or empty slogans or jokes. Ogilvy had little time for jokes, especially puns, his belief being that people didn't buy from clowns. It was Ogilvy, too, who penned in the same book the phrase: "The consumer isn't a moron; she is your wife."

Well, one can argue with that of course. Nobody, another pundit once said, ever went broke underestimating the intelligence of the average consumer. There is also more to be said about the use of humour than Ogilvy said in his book. But it still contains a lot of very sensible advice. It is difficult to gainsay his dictum that the most important words in an ad are those in the headline and that this should always tell a story and engage the reader's self-interest.

Certainly his own practice proved that long, informative ads could be very effective provided the heading was punchy and the copy was relevant and well written. What in sum he set out to do, and often did, was to produce press advertising that could compete with the surrounding editorial on its own terms.

And now to the Press Advertising Awards, sponsored by Campaign and chosen by a jury of marketing men and newspaper publishers as well as advertising professionals. Of the three Grand Prix winners I imagine Ogilvy would approve only of one. This was produced by the Saatchi and Saatchi agency for the Health Education Council and pictures a nude pregnant woman smoking a cigarette. The heading, clear, .meaningful and precisely targeted: "Is it fair to force your baby to smoke cigarettes?" But, of course, the ad, unlike all Ogilvey's famous campaigns, if not selling anything.

The other two grand prix winners are for Omega watches and the Times newspaper. The Omega ad, from the Dorland agency, occupies two pages. The first shows a picture of the watch in close-up with the heading: "Behind this smooth exterior beats a heart of stone." You have to turn the page to find "the heart of stone", i.e. the watch's interior, with factual and interesting copy explaining how it works. It's clever, but it's not the kind of sock-it-to-'em sales pitch Ogilvy recommended, since you have to get to the small print before you find the reason why you should buy.

As for the Times ad — a black page bearing only the newspaper's crest and the words, in white, "No pomp. Just circumstances" — this is surely something the old maestro would scoff at. The Times campagin by the Leo Burnett agency commits the sin, according to the Ogilvy canon, of relying on puns — another example is "Prose without the con" — and it contains nothing to persuade any nonreader of the Times that he ought to rush out and buy a copy.

The creators of the campaign would probably argue that their aim was not to recruit new purchasers but to reinforce the loyalty of existing ones, which is indeed what a lot of advertising is aimed at. Personally I'm dubious about the logic of reassuring Times readers with Guardian-style puns, but perhaps they know what they're doing.

Previous page

Previous page