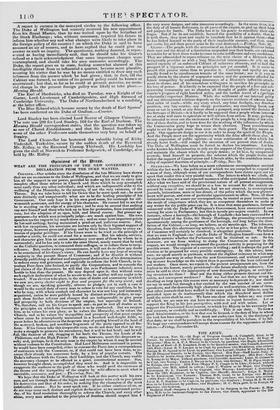

dopiniotti of the 19retti.

WHAT ARE TIlE PRINCIPLES OF THE NEW GOVERNMENT ? A DECLARATION FROM THE DUKE WANTED. Couarva—Our articles since the dissolution of the late Ministry 'have shown that we are no enemies to the Duke of Wellington, and that we are ready to give him all the support in our power, provided be make up his mind to carry into complete effect those reforms in Church and State which he may accomplish more easily than any other individual; and which are indispensable alike to the wellbeing of the Monarchy, to the security, if not the very existence, of the Throne. But we take leave to tell his Grace that he must speak out—he must state distinctly and unequivocally what are to be the leading principles of his Government. Our only hope is in his own good sense, his contempt for old- womanish nostrums, and the energy of his character. He cannot fail to see that he is standing on the edge of a precipice ; and he may be assured that nothing can save himself and those who look up to him for protection, from irremediable ruin, but the adoption of an open, bold, and liberal course. But present ap- pearances—by which men principally judge—are much against him. His own speeches are too vague to lay much stress on ; and on some most important points be has said nothing, having maintained a prudent and judicious reserve. But, with few exceptions, his associates are known only by their bigotted support of every abuse, however gross and glaring, and by their bitter hostility, to every ex- tension of popular privileges. If his Grace were to be tried on the principle of noscitur a sociis, he could not stand for a moment. But his talents, services, and character give him an entire ascendancy over most of those by whom he is surrounded ; and he has only to take the same liberal, manly course that he took on the Catholic question, to command their suffrages, or to reduce them to insig- nificance. But, under existing circumstances, it will not do to allow any doubt to be entertained of his Grace's views. He can hardly have any hope of securing a majority in the present House of Commons ; and if he dissolve it without formally publishing a distinct and unequivocal declaration of his determination to redress every real grievance, and especially to reform the Irish Church, to in- troduce Poor-laws into Ireland, to purify the Corporations, and to concede the hust claims of the Dissenters, he will find the next Parliament infinitely more ostile to him than the present. He may depend upon it, that without some such explicit declaration of what he means to do, he neither will nor ought to be trusted. Han election take place, in the state of doubt and uncertainty in which we now are, every elector ought to fear and prepare for the very worst; and though we are, speaking generally, adverse to pledges, yet in such a case it would be the sacred duty of every man to refuse to vote for any candidate, be he who he may, with whose conduct and character he was not long and intimately acquainted, unless he were publicly bound by distinct written pledges, to sup- port those further reforms and changes that are indispensable to give peace and prosperity to both divisions of the empire, but especially to Ireland. We, therefore, call on his Grace to speak out—to put to rest all doubts as to the principles on which the Government is to be conducted. But we conjure him, as he values his own glory, as be values the Monarchy, as he values the Church, and as he values the tranquillity and prosperity of that great empire whose cause he triumphantly maintained in a hundred well-fought fields, to

pause before he adventures on the desperate step of putting himself at the head of the scattered, broken, and worthless fragments of the party opposed to all Re- form. If his Grace take this irreparable step, we do not deny but that he may make a struggle to preserve bis ascendancy, but it will be but brief; and he will -fall, like Samsoir of old, dragging at his heels the Throne, the Lords of the Philistines, and the High Priests! He may, however, avert this desperate re-

sult; and, perhaps, he is the only man in the empire by whom it may be averted without violence to the Constitution. Had Lord Melbourne continued in power, he would have been compelled, either to concuss the Peers into a correspondence of sentiments with the Commons, or, if that could not have been done, to in- crease their already too numerous body, by a levy of popular recruits. The Duke's influence with the Crown, their Lordships, and the Church, may enable the necessary changes to be effected in a quiet, constitutional manner. But, however brought about, accomplished they tnust be. And it is impossible to exaggerate the madness or the guilt of those who would peril the existence of the throne and the tranquillity of the empire by wild efforts to avert what is inevitable, necessary, and just.— Thqrsilay, Nov. 20.

We hope that the Duke of Wellington a ill look at this matter with his own eyes, and not through those of the bigots and sycophants who sack to plc ipitate his destruction and that of his order, by making him the champion of the most indefensible abuses. But he must speak out. If be either continue silent, or do not issue some such distinct and explicit declaration as we mentioned yester- day, of his fixed resolution thoroughly to reform the Church, and every other abuse, every man attached to the principles of freedom should suspect him the very worst designs, and take measures accordingly. In the mean time it is the duty of all honest Reformers, in all par is of the empire, to gird up their loins

and prepare for battle. The Duke has it in his power to conciliate their suf.. frages. But if lie do not establish, beyond the possibility of a doubt, that he is with them, they must and ought to conclude that be is against them that he has linked himself to the party of their implacable enemies, and that, costa qui coute, his and their power must be for ever destroyed.—Friday, Nov. 21. GLOBE—The people. with the accession of an Anti-Reforniing Minister before their eyes and the dread of a dissolution suspended over their heads, are exhorted to remain for at least three weeks to come in calm indifference and easy confidence. They are admonished to repose reliance on the wise choice of a Monarch who benignantly provides us with a long Ministerial interregnum—to rely on the united capacity of an unformed Cabinet of unknown elements, and to hail the prospect of a vigorous action on principles not yet revealed. It is easier to preach this passive virtue than to practise it. Curiosity and apathy are not usually found to be simultaneous tenants of the same breast ; nor is It easy to pacify alarm by the charm of unpopular names, and the guarantee afforded for future tranquillity by conflicting assurances of a Minister's inflexible attach- ment to abuses, and of his scandalous willingness to sacrifice his principles to his love of power. It is hardly to be expected that the people of a free and self- governing community are to abandon all thought of public affairs during a courier's progress of eight hundred miles, and the tardier travel of a (perhaps reluctantly) expectant Minister. While the settlement of our internal policy and our inter national relations depends on the various accidents of sixteen hun- dred miles of roads--while any crazy wheel, any loOse linchpin, any drunken postilion, any lazy courier, any sleepy postmaster, any stumbling horse, any stone or rut iu a road, or any demur about a passport, may retard the decision of the fortunes of Britain—it is hardly to be supposed that a people whose interests are at stake will cease to speculate or will refrain from action. It may, perhaps, he intended to wear out the excitement of the people by a long delay of the solu- tion of their doubts, and to leave time for the working of the influences by which the Conservative party hope to secure their elections. These considerations ought to set the people more than ever on their guard. The delay means no good. Our opponents design to use it in order to damp the spirit of the People. And the People must use the opportunity which the delay affords them also. A strong expression of public opinion—a mere continuance of that which has already burst forth—will compel the cessation of our present state of doubt. The Duke of Wellington must be forced to declare his intentions. Let him make known his determination to rely on the support of the Conservative party, and maintain the abuses which the people detest; or let hi.n, by unequivocal avowals, bind himself to promote, the reforms which the people desire, and forfeit the support of Conservatives and Liberals alike, by the scandalous immo- rality of repeated desertion of principle.—Friday, Nov. 21.

STA NDA n—We have before its a most voluminous correspondence received within the last week ; the publication of which we are compelled to suspend by a sense of duty, although many of our correspondents have claims upon our re- spect that render this a very painful task. The letters to which we allude, all relate to the character and expected measures of the anticipated Administration. After what we have said of the provisional nature of all present arrangements, without any exception, we should be at a loss to account for the anxiety ex- pressed by some of our correspondents, had we not observed, in contemporary journals, intimations more or less direct, of the policy which the new gGvern • ment will pursue, and even of particular appointments to office. Now, all them intimations may, we assure our correspondents, be treated as pure invention, as the result of conjectures which they are as competent themselves to make as any writer fur the public press can be. It is true that some gentlemen, formerly connected with the Duke of Wellington's Government, have commenced can- vassing for seats in Parliament; but this is merely pro ntajore cautelti. In one instance, where a borough—the borough of Lambeth—has been canvassed for a personal friend of the Duke, Sir Henry Hardinge, the proceeding commenced spontaneously among the gentlemen of the borough, and long before the disso- lution of the Cabinet,—so long; we believe, as six months ago. The inference, therefore, from this electioneering activity, so far as it has gone, that the House of Commons will certainly be dissolved, is altogether gratuitous. We believe that no man in England—no! not the Duke of Wellington himself—can form a probable surmise whether the Parliament will be dissolved or not. So far, however, are we from wishing to damp the Conservative ardour in this respect, we would strongly recommend the greatest activity in preparing for the possible event. The expense of a canvass is trifling; and it is always the part of wisdom to be prepared for every possible contingency. In this advice, how- ever, we speak merely as partisans, without the slightest reverence to what may be expected one way or other from the new Government, and without pretend- ing to more knowledge on the subject than is possessed by the least informed of our readers. Once more, we repeat it, the present arrangements are, from the highest to the lowest, merely provisional—the future absolutely unknown. Can more be said to show the impropriety of now demanding pledges, or anticipat- ing occasions fur them ? Mums not the doing either promote distrust and dis- union, and consequent weakness ? But we feel that we are doing wrong in dwelling so long upon this course even as necessary to deprecate it; nor should we say so much but through a fear excited by the vast number of our corre- spondents, and the deservedly high character as well as station, of some of them, that other journals that have walked in the same path with us hitherto, may be prevailed upon to do inadvertently that which the Standard must decline until the crisis shall be over. We have one clear object before us; one course of which we are sure we can have no occasion to repent hereafter. Let us support the King in his just prerogative, with zeal and with union. Let us support the Provisional Government, to which his Majesty in his extremity has had recourse, as cordially and as confidingly. This is our duty. To form a good Administration, or the best that can be formed, is the duty of him to whom the task has been assigned. We must not embarrass him in the discharge of that duty, or we shall be partakers in the responsibility of his failure, if he fail. We hope our correspondents will accept these reasons for the suppression of their letters.—Friday, November 21.

Previous page

Previous page