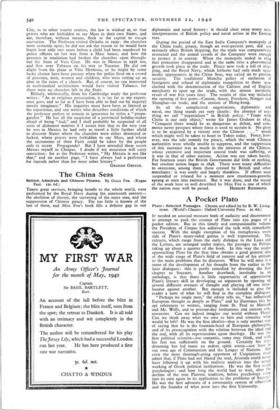

A Pocket Plato

Plato : Selected Passages. Chosen and edited by Sir R. W. Living- stone. (World's Classics : Oxford University Press. 28. 6d.) IT needed an unusual measure both of audacity and discernment to attempt to pack the essence of Plato into 220 pages of a pocket edition. But in this timely and companionable volume the President of Corpus has achieved the task with remarkable success. With the single exception of his metaphysics every side of Plato's many-sided genius is well represented.- The extracts, which range from the early dialogue to the Laws and the Letters, are arranged under topics, the passages on Politics taking up about a quarter of the book. In this way the reader approaching Plato for the first time obtains a good general idea of the wide range of Plato's field of interest and of his attitude to the main problems that he discusses. What he will miss is a sense of the development of his thought from the earlier to the later dialogues : this is partly remedied by devoting the first chapter to Socrates. Another drawback, inevitable in an anthology, is that there is little opportunity of appreciating Plato's literary skill in developing an argument by opening UP several different avenues of thought and playing off one inter- locutor against another. But enough is included to give the reader a taste of what he will find in the complete dialogues. "Perhaps no single man," the editor tells us, " has influenced European thought as deeply as Plato," and he illustrates this by apt references to writers, ranging from St. Paul to Masaryk and Mr. Wells, and to present-day institutions and current con- troversies. Can we indeed imagine our world without Plato? Can we think away what we owe to him and conceive what would be left? He was the first idealist—that is only another way of saying that he is the fountain-head of European philosophY, and of its preoccupation with the relation between the ideal and the real, with all its repercussions upon theology. He was the first political scientist—too romantic, some may think, and with his feet not sufficiently on the ground. Certainly his day- dreaming has led many an ardent spirit astray—not least in our own age of Communism and the League of Nations. But even the most thorough-going opponent of Utopianism must admit that, if Plato had not blazed the trail, Aristotle could neva have followed it up with his realistic analysis into the actual working of Greek political institutions. He was the first social psychologist : and how long the world had to wait, after the decline of the true Platonic tradition, before psychology came, into its, own again in its application to the problems of SocietY He was the first advocate of a community system of education and the founder of what grew into the first University.

No teacher is responsible for the vagaries of his disciples—least of all when he is a pioneer breaking into a vast unknown region of thought. One of the merits of Sir Richard Livingstone's little volume is that it sets Plato's work in its right proportions and recalls us to its chief underlying themes. Three in particular we find running through these pages. One is the insistence on absolute values—Truth, Beauty, Goodness—a view of life as hotly contested in Plato's day as in ours. Another is the neces- sary relationship between Politics and Morals. (Why is the first systematic European treatise on politics entitled "Concern- ing Justice" and not simply "Concerning Power "?) And the third is the possibility of promoting the good life in the com- munity by education—that is to say, by placing the younger generation under conditions in which their eyes are "turned towards the light" and their faculties can be fully developed. Plato called education the "gymnastics of the soul" and believed that it should go on throughout life. There is no body of students to whom his thought is more fitly addressed than those ranged under the banner of Adult Education. May many of them make acquaintance with him under Sir Richard Living-

Previous page

Previous page