FREETOWN AT A PRICE

Richard Snailham found much

unchanged in Sierra Leone since Graham Greene wrote 'The Heart of the Matter'

THE BANDSMEN of the Sierra Leone Regiment, hooked and eyed up to their necks in thick red serge, were oompahing away on a lower lawn in defiance of the heat and humidity. Suddenly they stopped. `First Vice-President, their Royal Highnes- ses the Duke and Duchess of Kent, Chair- man of the Committee of Management of Freetown City Council, distinguished ministers, members of the diplomatic corps and international institutions, the Mayor of Kingston-upon-Hull, my Lord Bishop, ladies and gentlemen . . . .' The High Commissioner, up on his balcony, had obviously attended many a Queen's Birth- day reception and spoke his lines with practised ease. What brought this motley crew to Runnymede, in the hills above Freetown? The Duke of Kent had presided over the granting of Sierra Leone's independence in 1961, so what could be more natural than that he and his wife should be invited to join in some of the junketing to mark the bicentenary of the colony's foundation. Why the Mayor of Kingston-upon-Hull was there — indeed, why any of us were there — has a more distant historical explanation. In 1772 Lord Chief Justice Mansfield gave judgment that a black slave called James Somersett was in fact free by virtue of having been brought by his owner from his West Indian plantation to Britain. This ruling had the effect of emancipating thousands of other black servants in Lon- don, Bristol, Liverpool and elsewhere, whereupon many of their employers -- in pique and to save wages — fired them, So we had a problem, long before Enoch Powell, of some 25,000 'indigent blacks' roaming city streets. This troubled the philanthropists of the day, variously known as the Evangelicals, the Clapham Sect or the Saints. Doyen of these Saints — and here we come, finally, to the Hull connec- tion — was the young William Wilber- force, life-long antagonist of the slave trade and slavery, who had been born in Hull, became its MP in 1780 at the age of 21 and is — if Andrew Marvell and Philip Larkin will allow it — the city's most famous son.

Wilberforce, Granville Sharp, Henry Thornton, Thomas Clarkson, et al, pon- dered the problem of the 'indigent blacks' and came up with the idea of repatriation. But where to? A botanist, Henry Smeath- man, had earlier been nosing around West African creeks and mangrove swamps and `Pride, envy and avarice have been promoted to virtues.' gave an unjustifiably roseate picture of Sierra Leone to the Committee for the Black Poor in 1786. The Treasury swal- lowed it and by April 1787 two naval vessels had sailed from Portsmouth with more than 400 settlers. In May they went ashore in Freetown harbour and hoisted a flag where St George's cathedral now stands. Wilberforce and his disciples had launched the Province of Freedom. That is why Hull and Freetown are twinned, and why Councillor Alf Bowd, Mayor of Hull, was now being hosted by his opposite number, Mr Alfred Akibo-Betts, resplen- dent in heavy velvet robes and tricorn hat.

Freetown harbour, one of the finest in the world and a haven for shipping since the Portuguese navigator Pero da Cintra first dropped anchor there in 1462, bears some resemblance, I suppose, to the Hum- ber estuary. Ocean-going vessels tie up at the Queen Elizabeth II deep water quay in Freetown as they do in Hull. During my visit I lived on board Operation Raleigh's support ship the Sir Walter Raleigh, the gift of the city of Hull to this great round-the- world enterprise for young people and at that time paying a fortnight's courtesy call for the bicentenary.

But the similarity ends there. No Hum- ber Bridge arcs across Freetown Harbour to link the city with the rest of the country. Instead, a slow ferry runs over to the Bullom shore opposite, where Freetown's international airport is most inconveniently placed at Lungi. There were expensive helicopter links to the Gun Wharf or the Mammy Yoko Hotel, but these have recently ceased.

I do not know the crime figures for Humberside but I would be prepared to bet that there is a great deal more thievery in Freetown. Taxi-men habitually wind up their windows on the way to the docks to thwart the snatching hands of streetboys. A De Beers friend of mine almost lost his wrist-watch in this fashion. Heavily laden lorries leaving the quay have to engage low gear and grind up a short incline. It is known locally as Thief Alley and security guards have to ride atop the sacks of rice to stop them being hauled off. We found that we could not always be sure about the security guards — quis custodiet ipsos custodes? — who seemed to work in collu- sion with the gangs of robbers that infest the docks area.

The [wharf] rats were cowards but dangerous — boys of sixteen or so . . . they swarmed in groups around the warehouses, pilfering if they found an easily-opened case . . . Gates couldn't keep them off the wharf; they swam around from Kru Town or the fishing beaches.

Within seconds of Sir Walter Raleigh's arrival from St Helena a dusky figure leapt from a dug-out canoe, climbed up the stern and in sight of the dumbfounded First Officer and a group of young venturers lifted a brand-new nylon mooring line from its bollard and dropped it into the harbour, where his accomplices cut away the end that had just been secured to the quayside. They were last seen, irretrievable and untraceable, paddling off to a nearby `pirate village'.

Deputy Commissioner Henry Scobie would have shrugged at the report of so familiar a crime and indeed nothing much seemed to have changed in other respects since Graham Greene was last there in 1943. Superficially the people appeared happy enough — except for those queuing for rice.

'How long will the rice shortage go on, Yusef?'

'You know as much about that as I do, Major Scobie.'

'I know these poor devils can't get rice at the controlled price.'

The country grows plenty of the staple food but it doesn't seem to get into the capital. The rural economy is increasingly a subsistence economy because motor trans- port, despite good roads built with West German help, is expensive, and the antiqu- ated narrow-gauge railway system which always used to carry rice and palm oil to Freetown was ripped up in 1979 and sold to the Moroccans. Ex-President Siaka Stevens, who died on 29 May this year, confessed recently that he should never have allowed the railway to go.

There is a general air of decay and decrepitude. Streets that looked neat and trimly pavemented in the photographs of the 1950s gape now with holes. Business is currently slack: the leone, which was un- realistically overvalued two years before at three to the pound, stood last May at 86. Nobody could afford anything. Air- conditioning salesmen, of which I seemed to meet several at the High Commission- er's reception, were particularly glum. The only happy faces were worn by Lebanese traders who have dominated the market in Sierra Leone for decades. When they have amassed a trunkful of useless leones they exchange them for a few diamonds, which are mined up-country near the Liberian border and rather easier to spirit out of the country and back to Beirut. Over 95 per cent of diamonds exported last year were smuggled, it is said.

`This is the orignal Tower of Babel,' Harris said. 'West Indians, Africans, real Indians, Syrians, Englishmen, Scotsmen . . . Irish priests, French priests . .

`What do the Syrians do?'

'Make money. They own all the stores up country and most of the stores here. Run diamonds too.'

Rich iron ore from the deposits at Marampa was once conveyed by rail to Freetown harbour, but the port installa- tions at Pepel were lifeless and rusting when I motored past them. Nor are the Italians at the moment progressing with their hydro-electric project above the Bumbuna falls. We have had our problems with British Telecom — as The Spectator knows as well as anybody — but a British American Tobacco Company operations manager told me that he had in nine months had only one call from elsewhere in Freetown and that company phones are limited to in-house use.

There are plenty of people with jobs but little work to do. The Sierra Leone Minis- try of Tourism down on Lightfoot Boston Street was typical. I called in for some material for a possible travel piece and found the Tourism Officer alone in his spare, dark office reading a newspaper. Girls in bright print dresses chdttered in adjoining rooms. 'No, I'm sorry we don't have any brochures just now. Try the Yasbek Tour Office.' But he was polite and thoughtful and gave me a 20-year-old atlas.

Arrivals and departures through Lungi Airport are an unmitigated nightmare. No order, no signposting, no queues, no in- formation. Plain-clothed youths latch on to confused arrivals and, in the expectation of a bit of dash, steer them through the bureaucratic chaos. Two forms have to be filled in before one may proceed past immigration. But they first have to be stamped. They can only be stamped by a bank clerk when he has changed £70 into a three-inch high stack of low denomination leones. These will prove difficult to get rid of in a short visit since hotels only accept hard currency. This virtual entry tax, cou- pled with a £25 visa makes Sierra Leone quite a pricey place to get into. Next, arriving passengers surge to the Passport counter, then to Customs, who invariably demand that cases are opened. It pays here to have had some experience on the rugby field, preferably in the second row of the scrum. There is much nicking and mauling as the baggage is extricated. Luckily I now had two aides one of whom, Mohammed, would have made a useful hooker in any club side, for my case came out cleanly through a forest of bodies.

Old West African hands will smile world-wearily and say that it is like this all along the coast, though for my money that does not make it any more tolerable in 1988. And it is the same in reverse on the way out. Small wonder that two travel companies have recently ceased operations to Sierra Leone because of the indignities to which their customers have been sub- jected at Lungi.

Only the vultures were about — gathering round a dead chicken at the edge of the road, stooping their old men's necks over the carrion, their wings like broken umbrellas sticking out this way and that.

I wondered how much President Joseph Momoh knew of what his tourists suffer. Probably not much, since he has more important matters of state to attend to. He is busy, for example, patching up things after a coup that failed in March 1987. Sixteen of its leaders were sentenced to death, two to prison terms. All are appeal- ing. Part of the Pademba Road, where they are incarcerated, was for a long time closed off to foil any rescue bid by Palestinian or other terrorist groups. Some Lebanese businessmen were implicated and were arrested. Five were expelled last June.

Furthermore, the Creoles of the Freetown area, who have all along filled the top positions in Sierra Leone, are now feeling themselves out in the cold, for the President is a Limba, one of the oldest tribes to settle in the region but one of the country's smallest.

The late Dr Siaka Stevens designated Momoh his successor and in 1985 it was a rare example of a peaceful transference of power M Sierra Leone's turbulent post- colonial history. Stevens had held in- creasingly autocratic power for 17 years, instilling fear and scattering dash like confetti. Despite the official eulogies most Sierra Leoneans now blame him for the present economic ills: he had instituted One-party government in 1978, reducing Parliament to a talking shop; he ignored the smuggling and the parallel market (which in a white country would be called the black economy) and turned a deaf ear to the IMF. The only thing Stevens is credited for is his ability to survive and for his handing over power three years ago.

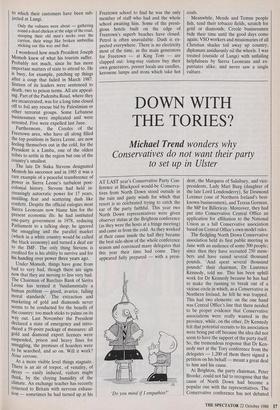

Under Momoh, things have gone from bad to very bad, though there are signs now that they are moving to less very bad. The Chairman of Barclays Bank of Sierra Leone has termed it 'fundamentally a human problem — greed, avarice, falling moral standards'. The extraction and marketing of gold and diamonds never seems to be conducted for the benefit of the country: too much sticks to palms on its way out. Last November the President declared a state of emergency and intro- duced a 59-point package of measures: all gold and diamond export licences were suspended, prison and heavy fines for smuggling, the premises of hoarders were to be searched, and so on. Will it work? No verrons.

At a more visible level things stagnate. There is an air of torpor, of venality, of decay — easily induced, visitors might think, by the cloying humidity of the Climate. An exchange teacher has recently returned to Britain with nervous exhaus- tion — sometimes he had turned up at his

Freetown school to find he was the only member of staff who had and the whole school awaiting him. Some of the presti- gious hotels built on the edge of Freetown's superb beaches have closed. Petrol is often unavailable. Dash is ex- pected everywhere. There is no electricity most of the time, as the main generators for Freetown — at King Tom — are clapped out: long-stay visitors buy their own generators, poorer locals use candles, kerosene lamps and irons which take hot coals.

Meanwhile, Mende and Temne people fish, tend their tobacco fields, scratch for gold or diamonds; Creole businessmen bide their time until the good days come again; VSO workers and missionaries of all Christian shades toil away up country; diplomats assiduously oil the wheels. I was treated (outside of Lungi) with 'unfailing helpfulness by Sierra Leoneans and ex- patriates alike, and never saw a single vulture.

Previous page

Previous page