BLASPHEMERS MUST DIE

John Mortimer talks to Kalim Siddiqui,

who supports Salman Rushdie's death sentence and Muslim separatism

'ONE of my children died. A boy. And after his funeral I bought a plot in the cemetery. So that future generations of Siddiquis may be buried here in Slough.'

I had driven down the M4, skirted Slough by the Beaconsfield road, turned right by the Do It All shop, and been lost in the rows of similar semi-detached houses, silent in the sunshine, fronted by sweet peas and dahlias and Ford Consuls. I was in search of Dr Kalim Siddiqui, head of the Muslim Institute, enthusiastic sup-

porter of the fatwa, the Iranian death

sentence on Salman Rushdie for the heinous crime of writing a novel which was short-listed for the Booker Prize. And somewhere, at some unknown address, a distinguished author was suffering his 19th

month in hiding, guarded by the SAS at a cost of £1,000 a day to the British tax- payer.

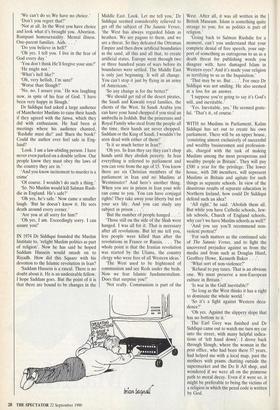

After knocking on a strange door and disturbing an Indian family, I telephoned the Doctor and he arrived to rescue me in his car. He is a short, tubby, perpetually smiling, frequently laughing man with grey hair and a beard. He was wearing flannel trousers, a fawn cardigan and a blue shirt. He looked exactly what he had been, a character around Fleet Street, an ex-sub

editor of the Guardian and one-time dramatic critic of the Kensington News. He

was no doubt well liked, full of jokes, buying rounds of drinks for the journalists in the pub and sticking to orange juice himself.

'The Rumpole man!' His greeting was extremely cheerful. 'I should have come to Henley-on-Thames to see you!' And when he led me into the headquarters of the Muslim Institute, a semi indistinguishable from his home next door, he was still laughing. 'Make yourself comfortable,' he

said, and I sat among the box files, the books on Islam and noticed Dr Siddiqui's British passport on the desk. 'Now what would you like? We can offer you coffee, Gold Blend. Or tea; here you have a

choice of Earl Grey or PG Tips.'

It was after he had fetched the tea and biscuits that he told me about the death of his son. He didn't speak without feeling but with a fatalistic acceptance of tragedy and, at the end, he couldn't stop chuckling at the long line of Siddiquis to be buried on British soil. I had come to discuss assasina- tion, religious persecution and the Gulf. It all seemed to be a long way from the sunshine in the suburbs of Slough. It was time to set about trying to understand a man who could countenance a murder because of the publication of a book.

'Tell me about yourself.'

'Not too much to tell, really,' 'You were born in India. Before Parti- tion?'

'Oh yes. My father was a policeman, in the British Raj. I went to school with a lot of Hindu boys. We always fought. The headmaster was a Hindu and he used to run up the Congress Party flag every morning and the British soldiers would come and cut it down. So one day the headmaster got some of the boys to throw stones at the soldiers, and a soldier raised his gun and fired at us. I will always remember a bullet whistling past my ear, and then I looked round and the boy behind me was dead. Now I just imagine a psych saying that this caused me to be a lifelong enemy of Britain. But I am not!' Dr Siddiqui chuckled happily. 'I have been very happy in England for 25 years. I am an extremely happy man.

'I left school and I was a student with no books. We were very poor. Then I started a paper in Karachi, but I sold it for £50 and came to England.'

'Why?'

'I had been ill, with malaria. And I was not happy with Partition.'

'You worked on the Kensington News.'

'Oh yes. The first time I had ever been in a theatre was as a dramatic critic. Then I worked on the Wokingham Times, the Northern Echo, the Slough Express. And eight years on the Guardian. I love the brotherhood of journalists.'

'You've said you're a typical Guardian man.'

'Oh yes, that's what I am. I have never voted except for old Fenner Brockway when he stood for Slough, and he didn't get in. Who's my favourite British politi- cian? I think Harold Wilson added greatly to the merriment, although he didn't achieve much.'

'In all your years in England did you encounter any racial prejudice. Against you, I mean?'

'Little pin-pricks, perhaps. Nothing se- rious. I am fair skinned. I could be a Spaniard. Oh, I think one fellow called me a "bloody Pakistani".'

What had I discovered so far? A Guar- dian man who, unusually for one of that species, thought irreligious writers should be put to death.

'What's the worst thing about The Sata- nic Verses, from your point of view?'

'Oh dear.' Dr Siddiqui's cheerfulness left him, and he sighed. 'I thought we were going to discuss more interesting matters than that! It is definitely the attack on the Prophet's personal character.'

Have you read the book?'

'Not from cover to cover.' Dr Siddiqui cheered up again. 'I have read a few pages. Funnily enough I was in Iran when the book came out. I was waiting in the VIP lounge for my plane when a Cabinet Minister came up to me. He asked me about Rushdie and I told him what I knew. At lunchtime that day the Imam pro- nounced the fatwa. I don't know if it was due to me at all.'

'The Islamic law is laid down by God, you believe?'

'Of course. And the sentence for blas- phemy or apostasy is death.'

'But isn't Christ part of the Islamic religion?'

'Oh yes. He is a prophet. We have to believe in his virgin birth.'

'And is the sentence death if you don't?'

'Quite certainly.' Making a mental note to advise the Bishop of Durham to be careful when travelling to the Middle East, I asked, 'Then don't the Christian virtues of forgiveness of sins, mercy, loving your enemies, have any part in your religion?'

`No part at all.' Dr Siddiqui laughed happily.

'Wouldn't you want to show forgive- ness?' We can't do so.We have no choice.' 'Don't you regret that?'

'Not at all. In the West you have choice and look what it's brought you. Abortion. Rampant homosexuality. Mental illness. One-parent families. Aids. . .

`Do you believe in hell?'

'Oh yes. I tell you. I live in the fear of God every day.'

'You don't think He'll forgive your sins?' 'He might not.'

'What's hell like?'

'Oh, very hellish, I'm sure!'

'Worse than Slough?'

`No, no, I assure you.' He was laughing now, in spite of his fear of God. 'I have been very happy in Slough.'

Dr Siddiqui had asked a large audience of Manchester Muslims to raise their hands if they agreed with the fatwa, which they did with enthusiasm. He had been at meetings where his audience chanted, 'Rushdie must die!' and 'Burn the book!' Could the author ever feel safe in Eng- land?

'Look. I am a law-abiding person. I have never even parked on a double yellow. Our people know they must obey the laws of the country they are in.'

'And you know incitement to murder is a crime' 'Of course. I wouldn't do such a thing.' 'So. No Muslim would kill Salman Rush- die in England. He's safe?'

'Oh yes, he's safe.' Now came a smaller laugh. 'But he doesn't know it. He sees death around every corner.'

'Are you at all sorry for him?'

'Oh yes, I am. Exceedingly sorry. I can assure you!'

IN 1974 Dr Siddiqui founded the Muslim Institute to, 'relight Muslim politics as part of religion'. Now he has said he hoped Saddam Hussein would smash on to Riyadh. How did this Square with his devotion to the Islamic revolution in Iran?

'Saddam Hussein is a rascal. There is no doubt about it. He is an undesirable fellow. I hope Saddam goes. But the point of it is that there are bound to be changes in the

Middle East. Look. Let me tell you,' Dr Siddiqui seemed considerably relieved to get off the subject of The Satanic Verses, 'the West has always regarded Islam as heathen. We are pagans to them, and we are a threat. So they defeated the Ottoman Empire and then drew artificial boundaries in the sand, all this and all that, to create artificial states. Europe went through two or three hundred years of wars before its boundaries were settled. The Middle East is only just beginning. It will all change. You can't stop it just by flying in an army of Americans.'

'So any change is for the better?'

'We should get rid of the desert pirates, the Saudi and Kuwaiti royal families, the clients of the West. In Saudi Arabia you can have your hand chopped if you steal an umbrella in Jeddah. But the princesses and Royal Family who steal from the people all the time, their hands are never chopped. Saddam or the King of Saudi, I wouldn't be seen dead with either of them!'

'Is it so much better in Iran?'

'Oh yes. In Iran they say they can't chop hands until they abolish poverty. In Iran everything is referred to parliament and you can vote from the age of 15. You know there are six Christian members of the parliament in Iran and no Muslims at Westminster? And here's another thing. When you are in prison in Iran your wife can come to you. You can have conjugal rights! They take away your liberty but not your sex life. And you can study any subject in prison . .

'But the number of people hanged . .

'Those still on the side of the Shah were hanged. I was all for it. That is necessary after all revolutions. But let me tell you, less people were killed than after the revolutions in France or Russia. . . . The whole point is that the Iranian revolution was started by the Ulama, the country clergy who were free of all Western ideas.'

'The West used to be frightened of communism and see Reds under the beds. Now we fear Islamic fundamentalism. Does that surprise you?'

'Not really. Communism is part of the West. After all, it was all written in the British Museum. Islam is something quite strange to you; for us politics is part of religion.'

'Going back to Salman Rushdie for a moment, can't you understand that your complete denial of free speech, your sup- port of something as outrageous to us as a death threat for publishing words you disagree with, have damaged Islam in Western eyes? And it's made your religion as terrifying to us as the Inquisition.'

'That may be so. But . . .'. For once Dr Siddiqui was not smiling. He also seemed at a loss for an answer.

'I suppose you're going to say it's God's will, and inevitable.'

'Yes. Inevitable, yes.' He seemed grate- ful. 'That's it, of course.'

WITH no Muslims in Parliament, Kalim Siddiqui has set out to create his own parliament. There will be an upper house, 'consisting almost exclusively of successful and wealthy businessmen and profession- als, charged with the task of making Muslims among the most prosperous and wealthy people in Britain'. They will pay £500 a year for the privilege. The lower house, with 200 members, will represent Muslims in Britain and agitate for such things as separate schools. In view of the disastrous results of separate education in Northern Ireland, how could Dr Siddiqui defend such an idea?

'All right,' he said. 'Abolish them all. But while you have Catholic schools, Jew- ish schools, Church of England schools, why can't we have Muslim schools as well?'

'And you say you'll recommend non- violent protest?'

'For such matters as the continued sale of The Satanic Verses, and to fight the uncovered prejudice against us from the media and from such as Douglas Hurd, Geoffrey Howe, Kenneth Baker . .

'What sort of non-violence?'

'Refusal to pay taxes. That is an obvious one. We must preserve a non-European culture in Britain.'

'Is war in the Gulf inevitable?'

`So long as the West thinks it has a right to dominate the whole world.'

`So it's a fight against Western deca- dence?'

'Oh yes. Against the slippery slope that has no bottom to it.'

The Earl Grey was finished and Dr Siddiqui came out to watch me turn my car into the street, with many helpful indica- tions of 'left hand down'. I drove back through Slough, where the woman in the post office, who had been there 57 years, had helped me with a local map, past the mothers with prams chatting outside the supermarket and the Do It All shop, and wondered if we were all on the primrose path to moral decay. Even if it were so, it might be preferable to being the victims of a religion in which the penal code is written by God.

Previous page

Previous page