Exhibitions

Jean Hellion (Tate Gallery, Liverpool, till 21 October) Braque: Still-Liles and Interiors (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, till 21 October)

Hen of the North

Giles Auty

When I wrote about the opening of the new Tate Gallery in Liverpool a little more than two years ago I expressed a fear that those who clucked and cooed so unctuously over this new babe-in-arms would fail to keep up their levels of affectionate interest. However, one hates to set oneself up as a prophet since what has occurred subsequently was far from hard to foresee. Today the Tate Gallery Liverpool limps along on a budget which is clearly inadequate and finds it very hard to attract sufficient local sponsorship. One must question whether Liverpool, rather than Manchester or Leeds, was the correct site for a Tate of the North in the first place. I fear that Liverpool, which is at a geographical dead end, was largely a sen- timental choice, since the other two cities are major road and rail junctions.

However, let us not wring our hands yet. I believe the answer for the Tate Liverpool is to establish a distinctive, maverick perso- nality, largely through its exhibitions poli- cy. Instead of being a pale echo of its mother in the south and of the often characterless modern art museums which throng northern Europe, it could set out instead to challenge and even change many of our often baseless assumptions about the values and character of modern art. As I have pointed out before, the term 'museum of modern art' is a misnomer unless we agree that 'modern' describes style rather than time. At present, museums of modern art everywhere, in- stead of concentrating simply on collecting and showing the best art of the era, exhibit an unjustified partiality for the formally innovative. It is clear, in fact, that the modern museum hierarchy values experi- ment — usually leading nowhere — above excellence. This is the direct reverse of the priorities held by the viewing public, whom such museums exist to serve. As proof of this I fear I must cite another recent forecast of mine which has been borne out by events. My premonition was that the portentous, pseudo-experimental British Art Show 1990 would set a new low attendance record for a summer exhibition at the Hayward Gallery. Many will think the exhibition's fate justified and my own sympathy goes only to the sponsors of the show, the venture capital house 31, who imagined they were supporting an embat- tled but deserving avant-garde.

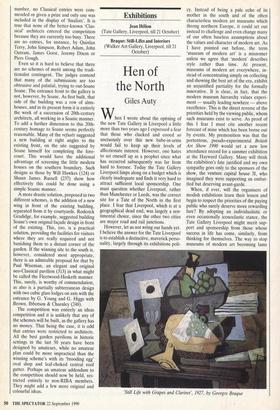

When, if ever, will the organisers of modish exhibitions learn their lesson and begin to respect the priorities of the paying public who surely deserve more rewarding fare? By adopting an individualistic or even occasionally iconoclastic stance, the Tate Gallery Liverpool might merit sup- port and sponsorship from those whose success in life has come, similarly, from thinking for themselves. The way to stop museums of modern art becoming lame 'Still Life with Grapes and Clarinet', 1927, by Georges Braque hens is by making their management aware, for the first time, of the reasonable requirements of an intelligent and long- suffering public.

How does an exhibition of the works of Jean Helion fit in with my suggested long-term survival plan for the Tate Gal- lery Liverpool? The claims made in the exhibition publicity that the Frenchman was a 20th-century artist of primary im- portance strike me as exaggerated. I met the artist in London in 1987 shortly before he died and am glad I expressed my admiration for his record of artistic inde- pendence. He is one of the few artists of note in this century who have made a conscious decision to swim against the tide of fashion. Helion was born in 1904 and grew to artistic maturity in the company of such fellows as Arp, Gabo, Miro and Mondrian. As the present show demons- trates, Helion, too, was an abstract artist of accomplishment but turned his back on the movement shortly before the second world war. As Helion remarked: 'I try to under- stand how, in spite of the elevation of the preoccupations of the abstract tendencies, their realisations are smashed by any Raphael or Poussin . . . When I compare the best works of today with Cimabue, I cannot doubt that Cimabue goes further.' These are brave words but Helion's ab- stract paintings have more in common with Poussin's classicism than do his later figura- tive works, which are often disordered and enigmatic. There are elements in Helion of the peasant-philosopher. He resisted the reductive process of abstraction in order to re-complicate once more. The many figurative works on view are the product of complex, sometimes contradictory inten- tions, yet seldom satisfy visually. Shades of Leger meld with a kind of proto-Pop in productions which are as likely to excite the psychiatrist as the aesthete. The exhibi- tion originates from the new modern art centre in Valencia which enjoys an annual budget some three and a half times larger than that of the Tate Liverpool.

While the exhibition of Helion's work will not be seen elsewhere in Britain, that of Braque's still-lifes and interiors now at the Walker Gallery moves on to the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery from 27 October to 9 December. At the time of Braque's death in 1963 his reputation in Britain seemed to have reached a pinnacle. Subse- quently the degree of interest in his work and, just as inexplicably, that of Paul Klee seems to have subsided steadily. I regret that the current exhibition, although the most important held here since 1956, looks unlikely to reverse this trend. Too few of the works on view demonstrate the rich- ness of which Braque was capable. A high proportion of the 32 paintings are extreme- ly sombre in tone. Their complex composi- tional organisations are easy to admire nevertheless and tend to show up the deficiencies of the artist's endless army of subsequent imitators who created a kind of Braque without bite. Theirs was the perva- sive art school style of my boyhood. Sometimes I think this century's true ori- ginals have a good deal to answer for.

Previous page

Previous page