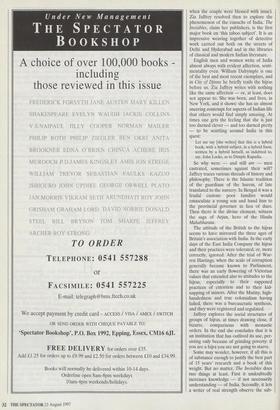

The lowest of the low

Allan Mallinson

THE INVISIBLES: A TALE OF THE EUNUCHS OF INDIA by Zia Jaffrey Weidenfeld, £15.99, pp. 293 Hijra, 'neither male nor female', is a word of Urdu origin, the language of the soldiers in the Mogul camps and bazaars, a combination of Hindi, Persian and Arabic. There are, say some, a million hijras in India today, although 50,000 is the 'official' estimate. Delhi and Hyderabad are their centres. In the (outlawed) caste system the hijras rate beneath the lowest, the harijans, the sweepers. They occupy a shadowy world and, like the European gypsies, they are at the same time welcomed as bringers of luck and reviled as extortionists.

Zia Jaffrey, whose mother Madhur took Indian cookery in this country beyond the take-away, first encountered the hijras in 1984 when she travelled to Delhi for a wedding. Outside the gates of the bride's house was a group of cross-dressing men who were singing out of tune and hurling insults at the guests. Finally, having brought luck to the union by their raucous presence, they were paid to leave (to return when the couple were blessed with issue). Zia Jaffrey resolved then to explore the phenomenon of the eunuchs of India. The Invisibles, claim her publishers, is the first major book on 'this taboo subject'. It is an impressive weaving together of detective work carried out both on the streets of Delhi and Hyderabad and in the libraries of classical and modern Indian literature.

English men and women write of India almost always with evident affection, senti- mentality even. William Dalrymple is one of the best and most recent exemplars, and in City of Djinns he briefly trails the hijras before us. Zia Jaffrey writes with nothing like the same affection — or, at least, does not appear to. She was born, and lives, in New York, and it shows: she has an almost sneering contempt for aspects of Indian life that others would find simply amusing. At times one gets the feeling that she is just too darned clever — and too darned pretty — to be scuttling around India in this quest:

Let me say [she writes] that this is a hybrid book, with a hybrid subject, in a hybrid form, written by a hybrid herself, as indebted to, say, John Locke, as to Dimple Kapadia.

So why were — and still are — men castrated, sometimes against their will? Jaffrey traces various threads of history and philosophy. There is the Islamic tradition of the guardians of the harem, of late translated to the nursery. In Bengal it was a feudal custom: poor families would emasculate a young son and hand him to the provincial governor in lieu of dues. Then there is the divine element, witness the saga of Arjun, hero of the Hindu Mahabharata.

The attitude of the British to the hijras seems to have mirrored the three ages of Britain's association with India. In the early days of the East India Company the hijras and their practices were tolerated, or, more correctly, ignored. After the trial of War- ren Hastings, when the scale of corruption generally became known to Parliament, there was an early flowering of Victorian values that extended also to attitudes to the hijras, especially to their supposed practices of extortion and to their kid- napping of minors. After the Mutiny, high- handedness and true colonialism having failed, there was a bureaucratic synthesis, and they were registered and regulated.

Jaffrey explores the social structures of groups of hijras, at times drawing close, if bizarre, comparisons with monastic orders. In the end she concludes that it is an institution that has outlived its use, per- sisting only because of grinding poverty: if you are a hijra you are not going to starve.

Some may wonder, however, if all this is of substance enough to justify the best part of 15 years' research and a book of this weight. But no matter, The Invisibles does two things at least. First it undoubtedly increases knowledge — if not necessarily understanding — of India. Secondly, it lets a writer of real strength observe the sub- continent with, in her words, 'a sense of otherness' — and a rare sense at that. Jaffrey's does not read as easily as other travelogues, but then what she writes about is not always attractive. She deserved better editing, though: why, for instance, do we need a footnote to explain that her Mills & Boons [sic] is a 'romance novel', but nothing to explain what is meant by 'a Maharashtrian actor's voice'. However, anyone who has read City of Djinns or its like should read The Invisibles: there can never be too many well-written books about India.

Previous page

Previous page