CUTTING OFF THE CAT'S TAIL

Anne Applebaum assesses the

contribution of outside advisers to Poland's rocky economy

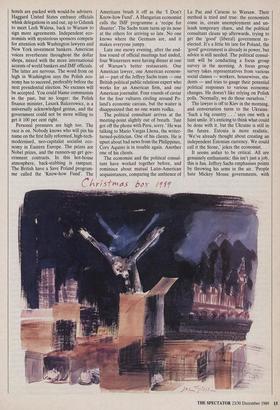

`DAMN.' Jeffrey Sachs is trying to call the Polish Ministry of Finance from his War- saw hotel room. 'Phones don't work here . . . I have to reach Paul Volcker in an hour.' He slams down the receiver. If Mr Sachs can't find him, the former chairman of the American Federal Reserve will miss his next meeting: another victim of the cruel Polish telephone system. Call- ing America is worse. Mr Sachs has figured out a way to do it through the AT&T operator in Denmark, but this isn't good enough. It doesn't look right for the Polish government to call collect. He thinks he has a quick solution. 'I'm trying to con- vince all of the ministries to put up telephone satellite dishes. Maybe we can get donations to do it,' he muses.

He is 30-something years old. He was born and bred at Harvard University. He oozes optimism. He is wreathed in legend. Single-handedly, he brought Bolivian infla- tion down from 40,000 per cent to 15 per cent in a matter of weeks. He preaches shock therapy: tighten the budget, cut the money supply, end inflation and create unemployment where there was none. Persuade the West to invest millions, even billions. Create a strong convertible cur- rency. Do it overnight. Do it next week.

He has made 12 trips to Poland over the last nine months, first as an observer, then as a latter-day gospel preacher. Now he camps out at the Warsaw Intercontinental, funded by the Hungarian millionaire George Soros, a semi-official adviser to the Polish government. He is as famous for the packaging and presentation of his ideas as he is for the ideas themselves. One leading Polish economist said he was overwhelmed by Mr Sachs, but can't decide if he's a charlatan or a genius. 'He thinks we're Latin-American,' the economist grumbled. What about privatisation? What about the obligations to Comecon, that worthy organisation which hangs like a millstone around Poland's neck? It sounds too easy.

`Look', says Mr Sachs, exasperated, `I've had experience with many countries in deep economic crisis . . . this is not the first country to have trouble with monopo- listic state structures.' But the Poles don't like being told they aren't unique, and Mr Sachs's distinctly un-Polish love of public- ity and speed fed more suspicions. When the Solidarity government took over from the communists last summer, he was there from the beginning, talking to the Polish press, the Polish parliament, writing edito- rials which everyone read in the Herald Tribune. In Washington, he alone did more for the cause of the Polish economy than the Polish government, the Polish embassy, and the Polish-American lobby put together. But for the Poles it's, well, too American. Mr Sachs says he once made the mistake of telling a Polish jour- nalist that it's better to cut off the cat's tail all at once, rather than piece by piece.

`Perhaps Mr Sachs wants to cut off the cat's tail at the neck,' commented the Communist Party Daily, with gleeful acid- ity. The communists should watch their sharp tongues: Mr Sachs is more than an economist. He's a pioneer, the man who paved the road from Latin America to Eastern Europe. Now, Warsaw's better hotels are packed with would-be advisers. Haggard United States embassy officials whisk delegations in and out, up to Gdansk to meet Lech Walesa, back to Warsaw to sign more agreements. Independent eco- nomists with mysterious sponsors compete for attention with Washington lawyers and New York investment bankers. American voices reverberate throughout the dollar shops, mixed with the more international accents of world bankers and IMF officials. The latter are nervous. The word from on high in Washington says the Polish eco- nomy has to succeed, preferably before the next presidential election. No excuses will be accepted. You could blame communists in the past, but no longer: the Polish finance minister, Leszek Balcerowicz, is a universally acknowledged genius, and the government could not be more willing to get it 100 per cent right.

Personal pressures are high too. The race is on. Nobody knows who will pin his name on the first fully reformed, high-tech- modernised, neo-capitalist socialist eco- nomy in Eastern Europe. The prizes are Nobel prizes, and the runners-up get gov- ernment contracts. In this hot-house atmosphere, back-stabbing is rampant. The British have a Save Poland program- me called the 'Know-how Fund'. The Americans brush it off as the 'I Don't Know-how Fund'. A Hungarian economist calls the IMF programme a 'recipe for disaster'. The Sachs team turns up its nose at the others for arriving so late. No one knows where the Germans are, and it makes everyone jumpy.

Late one snowy evening, after the end- less round of official meetings had ended, four Westerners were having dinner at one of Warsaw's better restaurants. One American lawyer, one American econom- ist — part of the Jeffrey Sachs team — one British political public relations expert who works for an American firm, and one American journalist. Four rounds of caviar for the four vultures circling around Po- land's economic carcass, but the waiter is disappointed that no one wants vodka.

The political consultant arrives at the meeting-point slightly out of breath. 'Just got off the phone with Peru, sorry.' He was talking to Mario Vargas Lhosa, the writer- turned-politician. One of his clients. He is upset about bad news from the Philippines, Cory Aquino is in trouble again. Another one of his clients.

The economist and the political consul- tant have worked together before, and reminisce about mutual Latin-American acquaintances, comparing the ambience of La Paz and Caracas to Warsaw. Their method is tried and true: the economists come in, create unemployment and un- leash temporary chaos, and the political consultant cleans up afterwards, trying to get the 'good' (liberal) government re- elected. It's a little bit late for Poland, the `good' government is already in power, but advice is still needed. The political consul- tant will be conducting a focus group survey in the morning. A focus group survey takes representatives from various social classes — workers, housewives, stu- dents — and tries to gauge their potential political responses to various economic changes. He doesn't like relying on Polish polls. 'Normally, we do those ourselves.'

The lawyer is off to Kiev in the morning, and conversation turns to the Ukraine. `Such a big country . . .' says one with a faint smile. It's enticing to think what could be done with it, but the Ukraine is still in the future. Estonia is more realistic. `We've already thought about creating an independent Estonian currency. We could call it the Stone,' jokes the economist.

It seems unfair to be critical. All are genuinely enthusiastic: this isn't just a job, this is fun. Jeffrey Sachs emphasises points by throwing his arms in the air. 'People hate Mickey Mouse governments, with Mickey Mouse rules. They want something serious,' he exclaims. Why can't the Poles see this too, what could go wrong? Political upheaval, worker backlash, all of this diminishes in the face of can-do optimism. Besides if it doesn't work, there's another team — probably ten other teams waiting on the sidelines to take their turn.

Previous page

Previous page