THE LIQUIDATORS MOVE IN

Edward Whitley meets

the men who make a living out of insolvency

`THERE was this one job when I went into the factory, stood up on a box and told them it was all over. The business was dead and they were all sacked. They could go home. Well, there was this stampede for the door. Everyone rushed into the car- park and jumped into their cars. Company cars, see? They were trying to nick them. I had seen this coming so my car was parked across the gate. Nobody could get out. Everyone was revving up and skidding around like it was Brand's Hatch. So my boys went in and began taking their car- keys. Some of them were trying to nick the radios.' Mr Langley tut-tutted mild dis- approval. 'Then it started to get a bit rough.'

I nodded in sympathy.

And then there was this meat trader. He went bust. I was in there two hours later, changed the locks and began running it. There I was trading dead meat for six weeks. In at four in the morning, pitch black, counting the carcasses into the warehouse and counting the pieces coming out the other side. Give or take a bit of sawdust they had to add to the same number of carcasses as had come in.' Real accountancy I jotted down. 'All these meat-boners were carving them up. They wore chainmail sleeves on their arms their knives were that sharp. Awesome.'

Mr Langley cut an effortless swathe through an imaginary carcase. 'The next week I had this big Irish meat trader on the phone. He said that half the stock was his. He was claiming right of retention. So I said to him: Listen Paddy, you come over here and let's sort it out. Come round to the warehouse nice and early, let's sort it out. Come round to the warehouse nice and early, let's say around four. I'll be there. What's your cow's name? Daisy? Well you come in the front door and shout out for Daisy. If she comes running then she's yours. Otherwise back off.'

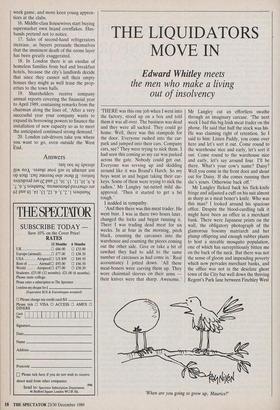

Mr Langley flicked back his flick-knife fringe and adjusted a cuff on his suit almost as sharp as a meat boner's knife. Who was this man? I looked around his spacious office. Despite the blood-curdling talk it might have been an office in a merchant bank. There were Japanese prints on the wall, the obligatory photograph of the glamorous bosomy matriarch and her plump offspring and enough rubber plants to host a sizeable mosquito population, one of which has surreptitiously bitten me on the back of the neck. But there was not the sense of gloom and impending poverty which now pervades merchant banks, and the office was not in the desolate ghost town of the City but well down the thriving Regent's Park lane between Finchley West `When are you going to grow up, Maurice?' and Golders Green, opposite the Datsun dealer-ship. In the car park outside stood a Jaguar, a convertible BMW, a Porsche and a Rolls Royce. Mr Langley, partner of Sorskys Specialised Financial Services, was not worried about his mortgage, his next bonus or the gaping jaws of recession opening up beneath him. In fact the faster, the bigger and the more savagely the recession bites, the happier he will dance on its teeth. Mr Langley is a liquidator and unlike a merchant bank the cars outside belong to him and his partners rather than their clients. After four dull years of general economic prosperity his business is set to boom.

His excitement is well supported by recently published statistics. Trade Indem- nity, the credit insurer, published figures which showed that the number of company insolvencies will be up from 9,500 last year to some 12,000 this year, a 25 per cent increase. As for next year there is exuber- tant talk that it will break the record of 15,000 set in 1984 at the tail-end of the 1979 recession. Accountants Peat Marwick McClintock have counted 840 companies going into receivership in the first nine months of this year, a 40 per cent increase on last year. Every Wednesday the High Court of Justice publishes a list of com- panies facing compulsory liquidation. For the last two months this has gratifyingly taken up two sides of foolscap rather than the usual single sheet. In Mr Langley's enthusiastic opinion this is just the begin- ning.

`People are just hanging on until Christ- mas. That's all they want to do. Get through Christmas, buy the kiddies nice presents and then. . .' He drew an express- ive finger across his throat. 'We call it the Turkey Syndrome.'

For Mr Langley and his fellow liquid- ators the New Year is poised to be the munificent provider of a glut of cold turkey. All the ingredients of the perfect recipe for insolvency are at hand: high interest rates, high rents, high wage de- mands, high inflation, over-capacity, low customer demand and low bank credit.

Corporate insolvency divides between receivership and liquidation. Although all insolvency practitioners are qualified to handle both receiverships and liquidations, there are various differences which result in the Big Six accountants monopolising company receiverships and a large number of small liquidators fighting amongst them- selves for the left-overs. The reason for this virtual monopoly is that a receiver can only be appointed by a debenture holder who has a fixed and floating charge over the company's assets. This is typically a bank. The receiver's responsibility is only to recover the secured debts owed to this debenture holder. He has little concern for the rest of the unsecured creditors and once he has accumulated sufficient funds to repay the debenture in full his task is completed. Although the company might conceivably then emerge from receivership to commence trading again — in Mr Langley's words 'The Phoenix Syndrome' — there is generally little left of the business and the outstanding creditors will appoint a liquidator — 'The Bad News Syndrome'. The liquidator is appointed at an open meeting of creditors and it falls to him to carve up the rest of the carcase and divide any further cash amongst the credi- tors. The average returns to creditors from a company in liquidation is just one penny in the pound.

Thus when receivers are appointed, the company is still a going concern. It might continue to trade, there are probably saleable assets and there may be willing buyers for the profitable parts of the business. As it is generally one of the Big Four high street banks which appoints a receiver, they tend to appoint one of the Big Six accountancy firms in a mutually beneficial arrangement which helps each other grow bigger. As a receiver ranks above the liquidator in the pecking order of repayment, when a company has gone straight into liquidation it is not unknown for a bank to appoint a receiver over the liquidator's head, a process which Mr Langley finds particularly irksome.

The large accountants have come a long way since Mr Touche and Mr Deloitte used to solicit business on Carey Street. When visiting their offices it is difficult to believe that you have arrived-in Queer Street. The matt black furniture and lime green pencil cases indicate a modern, sophisticated approach to the sort of problems their clients might be experiencing. Leaflets in reception mention 'Financial re- organisations', 'Restructuring' and 'Volun- tary arrangements'. There is no crass men- tion of the single thing which is preying on the client's mind and is most urgently needed: money. Michael Jordan of Cork Gully, part of Coopers and Lybrand, adopts a melancholic tone and talks of `storm clouds gathering' and how 'we are doing an awful lot of pre-emptive corpo- rate care work' as if he is an unpaid social `Looks like flu, Rudolph.' worker. Christopher Morris at Touche Ross sports the same half-moon spectacles but his approach is rather more belt and braces — in his case broad red braces with blue dots. He has no qualms about looking forward to the upsurge in business next year. Cheerful and flamboyant, he is the Galloping Gourmet of the cold turkey world.

The relationship between receivers and accountants can be seen as the same as the relationship between undertakers and doc- tors. The receivers provide a dignified end to the company, look after the principal beneficiaries and everyone walks away believing something good has come out of the experience. Just as undertakers avoid all mention of the word 'Death' so receiv- ers avoid all mention of the word 'Money'. If receivership is the accounting equivalent of undertaking, liquidation is the autopsy. However, rather than being privately appointed with quiet dignity, the liquidator has to fight over the corpse for the busi- ness. He is appointed at a public meeting of creditors, who will not be best disposed towards the company's directors.

I attended such a meeting, and it was rather like the worst of the American chat shows. The liquidator sat up at a table with the luckless directors of the company, in this case a bathroom supplier. The atmos- phere in the room suggested that if the creditors were not going to get their penny in the pound, they would at least try to get their pound of flesh. The liquidator read out the dismal report of the company's trading history. When asked what went wrong — how did he lose £200,000 in six months? — the director blamed high in- terest rates.

`I thought as much,' one creditor said. `Bollocks', was the erudite comment of my neighbour.

The liquidator alternately excused the directors for being the hapless victims of vicious circumstances or excoriated them for mismanagement. The directors sat sul- lenly in the middle of this banter, their heads bowed. The liquidator knew he was guaranteed a laugh from the floor at any time and scored quite nicely when asked his opinion about the chairman's rela- tionship with his bank manager, 'A love affair I'd say.' Then with a sidelong glance at his silent neighbour he added, 'Or perhaps not.' With the flair of a profession- al host he saved his best until last. When discussing the future prospects, the direc- tor admitted that he was going to start up a new business. 'What will you call it?' asked one creditor, keen to avoid supplying it.

`Venezia Limited.'

`Italian,' the liquidator murmured appreciatively. 'Do you think that will enhance the business?'

The roar of laughter from the floor obscured my neighbour's question of 'How are you spelling that then?'

At creditors' meetings the liquidator is appointed by a majority vote. Creditors vote on a pro-rata basis to the liquidators from amassing private armies of creditors to vote themselves into office, the small liquidators tend to convene creditors' meetings at 4 p.m. in an obscure hotel in Coventry or, equally obscure, their offices.

When you eventually arrive at these offices you immediately recognise where you are: Queer Street. The offices of Stuart Edgar, 'Financial Consultant', are tucked away in the corner of a large square in Islington. The reception comprises a line of three chairs in the corridor just a nose length away from the wall. I sat down and crossed my legs with difficulty. I noticed a series of black scratch marks where pre- vious shoes had scraped the wall in the same manoeuvre. Two copies of Accoun tancy were on a side table.

Stuart Edgar himself is a surprisingly young man. In his opinion one of the prime skills a liquidator must have is to know how to sell anything. At the drop of a hat they might be trying to sell 6,000 pairs of industrial rubber gloves, a collection of last year's lingerie or 2,000 cricket balls in November. In these murky waters there is clearly a good deal of scope for conflict of interest. Stuart Edgar told me how when word got around that he was selling a company yacht he was the most popular man in Islington for six weeks. Melvyn Langley was once appointed liquidator to a company which manufactured casino chips. As work in progress they were worthless plastic. As finished stock they were the closest thing to straight cash with the added attraction of no serial numbers.

So when the Christmas euphoria clears and we find ourselves staring down the barrels of insolvency, where do we go? At whose reception do we all meet up? The matt black furniture with lime green trim- mings or the scuffed wall? Just as life ranges from the sublime to the ridiculous, so the after-life of insolvency ranges from the urbane to the treacherous. One thing which should be clear about all insolvency whether we turn down the primrose Queer Street in the City or stumble into Queer Street in Islington is that the person who will come out best is --- of course — the professional. Both as receiver and liquida- tor the insolvency practitioner makes his money at the expense of the company and the creditor. He will charge a 15 per cent commission on all monies which he man- ages to retrieve, a charge calculated before taking any tax liability into consideration. As an incentive for him actually to pay monies out to the creditors, he also charges a 15 per cent commission on all monies paid out. In this way they are the only people to rival the financial affrontery of the Fine Art auction houses who charge a similar commission to both seller and buyer. When dealing with such sharp practitioners, our chances of emerging unscathed are about as good as the chances of Paddy's cow Daisy being able to run out of the meat packing warehouse.

Previous page

Previous page