HOLY AND DIVIDED

Piers Paul Read looks at this

extraordinary meeting place of three world religions

AN EARLY achievement of the Palesti- nian intifada — Jerusalem is once again a divided city. There is no Green Line or Mandelbaum Gate, but the Jews I met in West Jerusalem were afraid to cross to the Arab side of the city and the Arabs from the East only seem to go to West Jerusalem to work or set cars on fire. Old friends of my parents — pioneer Zionists — who live in Rehavya are even afraid to walk in the park beneath the Knesset because an old man was murdered there more than a year ago. They are confined to the streets of Jewish Jerusalem as if in a ghetto.

There are other ironies. One of the long, low buildings of the Russian compound built by the Tsars for orthodox pilgrims in the 19th century — was used by the British during the mandate as a prison for Jewish terrorists (or freedom fighters, depending upon one's point of view). It is now preserved as a museum: there is a gallows and a condemned cell although the half- dozen or so who were sentenced to death were in fact executed in Acre. The irony is that only two hundred yards away on the other side of the Orthodox Cathedral a similar building is now being used for a similar purpose by the Israeli police. A

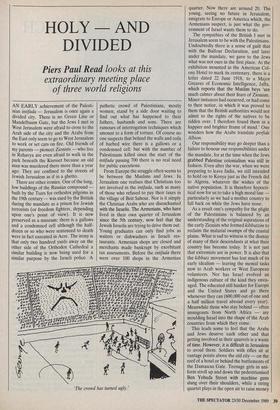

pathetic crowd of Palestinians, mostly women, stand by a side door waiting to find out what has happened to their fathers, husbands and sons. There are rumours of interrogation techniques which amount to a form of torture. Of course no one suspects that behind the walls and coils of barbed wire there is a gallows or a condemned cell: but with the number of Palestinians killed since the start of the intifada passing 700 there is no real need for public executions.

From Europe the struggle often seems to be between the Muslims and Jews. In Jerusalem one realises that Christians too are involved in the intifada, such as many of those who refused to pay their taxes in the village of Beit Sahour. Nor is it simply the Christian Arabs who are disenchanted with the Israelis. The Armenians, who have lived in their own quarter of Jerusalem since the 5th century, now feel that the Jewish Israelis are trying to drive them out. Young graduates can only find jobs as waiters or dishwashers in Israeli res- taurants. Armenian shops are closed and merchants made bankrupt by exorbitant tax assessments. Before the intifada there were over 100 shops in the Armenian `The crowd has turned ugly.' quarter. Now there are around 20. The young, seeing no future in Jerusalem, emigrate to Europe or America which, the Armenians suspect, is just what the gov- ernment of Israel wants them to do.

The sympathies of the British I met in Jerusalem seem to be with the Palestinians.

Undoubtedly there is a sense of guilt that with the Balfour Declaration, and later under the mandate, we gave to the Jews

what was not ours in the first place. At the exhibition mounted in the American Col- ony Hotel to mark its centenary, there is a letter dated 22 June 1918, to a Major Greaves of Economic Intelligence, Jaffa, which reports that the Muslim beys 'are much calmer about their fears of Zionism. Minor instances had occurred, or had come to their notice, in which it was proved to them that the British authorities would not admit to the rights of the natives to be ridden over. I therefore found them in a happier and brighter frame of mind.' One wonders how the Arabs translate perfide Albion.

Our responsibility may go deeper than a failure to honour our responsibilities under the mandate, for at the time when the Jews grabbed Palestine colonialism was still in fashion. Even after the war, when we were preparing to leave India, we still intended to hold on to Kenya just as the French did to Algeria, whatever the wishes of the native population. It is therefore hypocri- tical now for us to take a high moral line particularly as we had a mother country to fall back on while the Jews have none.

As a result one's sympathy for the plight of the Palestinians is balanced by an understanding of the original aspirations of the early Zionists who formed kibbutzim to reclaim the malarial swamps of the coastal plains. What is sad to witness is the dismay of many of their descendants at what their country has become today. It is not just that extremists are in power. It is also that the kibbutz movement has lost much of its early idealism — leaving the menial tasks now to Arab workers or West European volunteers. Nor has Israel evolved an indigenous culture of the kind they envis- aged. The educated still hanker for Europe and the United States and go there whenever they can (600,000 out of one and a half million travel abroad every year). Meanwhile those who stay behind — often immigrants from North Africa — are moulding Israel into the shape of the Arab countries from which they come.

This leads some to feel that the Arabs and Jews deserve each other and that getting involved in their quarrels is a waste of time. However, it is difficult in Jerusalem to avoid them. Soldiers with rifles sit at vantage points above the old city — on the roof of a hotel or behind the battlements of the Damascus Gate. Teenage girls in uni- form stroll up and down the pedestrianised Ben Yehuda Street with machine guns slung over their shoulders, while a string quartet plays in the open air to raise money for cancer research. Every day there is a story in the Jerusalem Post of the death of a Palestinian or the murder of a Jew. In the tight throng in the narrow streets of the Arab quarter I felt relieved not to look like either an Arab or a Jew.

I was also glad to be staying at the American Colony Hotel. Once the house of pious pioneers from Chicago who moved to Jerusalem in the 19th century, it still belongs to the descendants . of the original owners. It is easy to see why it is so popular with Gentile visitors to Jerusalem. It is on the Arab side of the city, so one feels that one has travelled to the Middle East, not to the American Middle West as one does at times in West Jerusalem. Guests are not constrained by the Jewish dietary laws which are imposed in the hotels in West Jerusalem, nor trapped in the air-conditioned anonymity of a hotel that could as well be in Las Vegas. While I stayed at the American Colony a party was thrown to celebrate the centenary of that hotel which was unusual in that it brought Arabs and Jews together under the same roof. Jewish doctors also work voluntarily at the Spafford Children's Centre in the Arab quarter of the Old City which is run by a member of the Vester family and subsidised by the hotel.

With or without the intifada, Jerusalem is an extraordinary city — not just for its association with three major religions, but as an archaeological treasure trove where the works of David, Solomon, Herod, Titus, Hadrian, Constantine, Abd al- Malik, the Crusaders and Suliman the Magnificent are still to be seen. Even now new discoveries are being made: a passage has been dug along the full length of the western wall of the Temple which reveals that the Second Temple was never com- pleted. Above, a week or two before, a group of Jewish zealots provoked a riot when they tried to break into the Muslim- held Temple Mount to lay the foundations of a new Third Temple. Nowhere else in the world does the past meet the present in the same way.

Its also the Holy City which reminds us that Christ was an historical, not a mythic- al, figure who walked on the huge Hero- dian paving stones which in places have been uncovered. In archaeological terms they are almost recent — for what is 2000 years in human history when, in the Rockefeller Museum, there is the skull of a man found in Galilee which is 120,000 years old? Of Christ, of course, there is no skull on display but, in a hotchpotch of a church now being restored, and beneath an absurd kiosk from the 19th century, there is the tomb where he rose from the dead. Some yards away, in the same church, is the summit of Golgotha — the site of the crucifixion. There for a moment the jour- nalist and novelist in me gave way to the pilgrim and I prayed as best I could with the sound of the stonemason's drill in my ear.

Previous page

Previous page