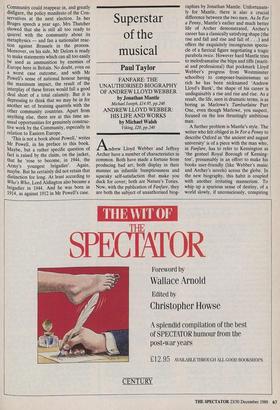

Superstar of the musical

Paul Taylor

FANFARE: THE UNAUTHORISED BIOGRAPHY OF ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER by Jonathan Mantle

Michael Joseph, 114.95, pp.248

ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER: HIS LIFE AND WORKS by Michael Walsh

Viking, £20, pp.240

Andrew Lloyd Webber and Jeffrey Archer have a number of characteristics in common. Both have made a fortune from producing bad art; both display in their manner an infantile bumptiousness and squeaky self-satisfaction that make you duck for cover; both are Nature's Tories. Now, with the publication of Fanfare, they are both the subject of unauthorised biog- raphies by Jonathan Mantle. Unfortunate- ly for Mantle, there is also a crucial difference between the two men. As In For a Penny, Mantle's earlier and much better life of Archer demonstrated, Archer's career has a classically satisfying shape (the rise and fall and rise and fall of . . .) and offers the exquisitely incongruous specta- cle of a farcical figure negotiating a tragic parabola twice. However hard Mantle tries to melodramatise the blips and tiffs (marit- al and professional) that pockmark Lloyd Webber's progress from Westminster schoolboy to composer-businessman so rich he has been nicknamed 'Andrew Lloyd's Bank', the shape of his career is undisguisably a rise and rise and rise. As a result, the life, seen in dramatic terms, is as boring as Marlowe's Tomb uriaine Part One, even though Marlowe, you suspect, focused on the less thrustingly ambitious man.

A further problem is Mantle's style. The writer who felt obliged in In For a Penny to describe Oxford as 'the ancient and august university' is of a piece with the man who, in Fanfare, has to refer to Kensington as `the genteel Royal Borough of Kensing- ton', presumably in an effort to make his books user-friendly (like Webber's music and Archer's novels) across the globe. In the new biography, this habit is coupled with another irritating mannerism. To whip up a spurious sense of destiny, of a world slowly, if unconsciously, conspiring in the creation of Lloyd Webber's smash- hit musicals, Mantle peppers his chronolo- gical narrative with portentous intimations of the triumphs-to-come, reminding you, for example, that during the Fifties when Andrew was a short-trousered schoolboy, Eva Peron was dying and passing into legend in Argentina, or that in 1965, as Andrew was preparing to go up to Mag- dalen, T. S. Eliot 'whose poetry had perplexed many a Westminster English A Level candidate' died. The only surprise is that when he announces Andrew's birth, Mantle manages to resist adding that 'just 1,948 years before, and many miles east of Kensington, Jesus Christ had been nailed to a cross.' Certainly you would think that the claims to fame of these notables were as nothing compared to their connection with Webber's musicals.

Some intriguing points emerge. Tim Rice had to browbeat a stolidly reluctant Lloyd Webber into writing the show about Eva Peron. (It eventually took £23 million at the box office in London alone.) Ex- tracts from newspaper interviews with the second Mrs Webber, Sarah Brightman who at 16 was already wiggling her way to public notice with Pan's People — reveal her as a mistress of mock-reluctant self- promotion. Here she is at 18: `I didn't start out to be sexy', she giggled, 'It just happened that way. I don't mind at all it's quite a fun thing . . . Anyway, you'd be surprised how difficult it is to dance with lots of clothes on.'

Her husband, the first composer to have a company floated on the stock exchange, adopts much the same tone when talking of his wealth.

Despite nuggets of good gossip about the people Webber has dropped, his personal- ity clashes with collaborators and his spats, as yuppy squire of Sydmonton, with the villagers of Ecchinswell, the book has a distinctly insubstantial feel. Instead of tackling head-on the crucial question of whether Webber's music is indeed as synthetic and soullessly plagiaristic as its detractors claim, Mantle approaches it obliquely and gingerly through quotes and insinuations. Not, you surmise, that he would be qualified to deliver a verdict on musical-theatre issues. From an allusion on p.108, he clearly thinks that it was George Bernard Shaw who advised Mrs Worthing- ton not to put her daughter on the stage.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, Michael Walsh, the music critic of Time magazine, is only too willing to tell you, for example, that the `plagal half-cadence is a favourite Lloyd Webber melodic device' in his new, densely detailed and lavishly illustrated coffee-table book on the com- poser's life and works. Exhaustively re- searched, this slab-like tome nowhere establishes that Lloyd Webber's work merits such a monument of misplaced scholarship. Perhaps the final, blessedly succinct words on the subject should be left to fellow-composer Alan Jay Lerner. 'I don't know why, Alan,' Andrew once confided in him, 'but some people dislike me as soon as they meet me.' Perhaps,' replied Lerner, 'it saves time.'

Previous page

Previous page