TWENTY YEARS ON

Sandra Barwick revisits her

old school, which has gone through several educational revolutions

ST AIDAN'S school in Carlisle still smells much as it did. The assembly hall is still pervaded with the heavy aroma of school dinners, that sickly blend of cabbage, custard and mincemeat of 20 years ago.

In 1970, when I was a pupil there, not much else survived the reformists. That year the brave world of comprehensive education had just obliterated Carlisle and County High School for Girls which had occupied the buildings for almost 70 years, its strong academic standards, its grey and maroon uniform, its highly dedicated and qualified female staff, its competitive, hierarchical, — some thought snobbish — discriminatory, old-fashioned system. Its demise reflected the spirit of an age and so, perhaps, do present events.

Aged 16 in 1970, I had just mastered the old system and learnt how to poise my maroon beret at what I hoped was a rakish angle which would demonstrate seniority over juniors while irritating seniors. When the change came and replaced my school with a comprehensive named St Aidan's, all I knew was that life had become modern and progressive. Where we were progres- sing, and why, remained mysterious. Car- lisle High School had not taught the questioning of authority. I was one small product on the academic assembly line, and the factory had been re-fitted. No one asked the pupils' opinions. No one asked the parents. No one asked the teachers. A new egalitarian and democratic age was imposed from above.

I see now that this progressive regime was, in its way, a superior preparation for life than that offered by the High School — my old grammar school. From being an ordered, disciplined structure in which obedience and virtue were rewarded, my 'I hate his more endangered than thou attitude.' world became grey, anonymous and in- coherent. Survival replaced enjoyment.

There was no shortage of funds. New buildings sprang up for the study of metal- work and woodwork and a vast indoor sports hall appeared.

The new age of equality obliterated the compulsory school uniform, prefectorial offices and prizes for academic achieve- ment. Mass assembly in the morning was gone. The school had almost doubled in size, from 600 to over a thousand: no one room could hold us. We were now a mixed-sex school, but the senior teaching posts were held almost exclusively by men, and strange men some of them seemed. The headmaster startled me by his only remark in three years, as I leaned against a corridor wall: "You're looking very S- shaped today."

The head of sixth told me that he was not very concerned for the welfare of the sixth form on the grounds that we were always going to survive. He was more worried about the children in the remedial classes who could not read the writing on a cigarette packet. The idea that we might all be educated to reach our optimum did not seem to be current. This kind of attitude may help to explain why some Cambridge colleges have had to start positive discri- mination to help let in state pupils. Under the new system at St Aidan's there was, of course, no tuition for the Oxbridge entr- ance examination, but there was education of another sort, for through our purple corridors blew a strong political breeze. At compulsory general studies periods we watched a series of anti-war films, where poppies faded, women wept to a backdrop of nuclear explosion, and plaintive guitars twanged a farewell over ranks of military gravestones.

I made my own farewell to the place with relief and anger three years after its meta- morphosis. Not much disturbed my efforts to forget it in the years that followed: there was an article in one of the Sunday supplements which compared St Aidan's and Eton as opposite ends of the spectrum; and in 1983 one of the senior masters, seen by other members of staff as 'a brilliant innovator', was given a suspended six- month prison sentence for spanking the bottoms of 13- and 14-year-old girl pupils through their nightdresses with a training shoe. The girls' parents had been present throughout these innovatory spankings, convinced by his authority that he must know best.

Other than from these stories it was hard to tell the successes of the new order, because the headmaster did not publish examination results. It is true that general- ly the success of the comprehensive move- ment is hard to quantify. Some compre- hensive schools have an excellent reputa- tion; as a whole they have not succeeded in sending more working-class children to university than before, but perhaps that was never the aim. What is quite clear is that the population of this country, relying on the unscientific but persuasive evidence of their own experience and that of chil- dren of relatives and friends, has little faith in the present educational system. Only 37 per cent of the British, according to the latest Gallup survey, are confident in the quality of the nation's education, com- pared with over 70 per cent in Denmark and West Germany. Certainly it was on unscientific evidence that parents, unen- lightened on the matter of educational theory, were, in the end, the judge of the regime at St Aidan's.

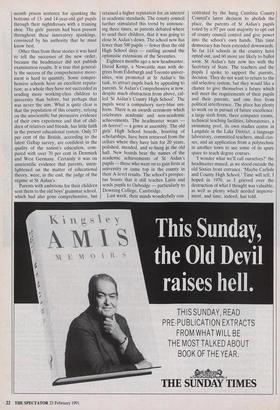

Parents with ambitions for their children sent them to the old boys' grammar school, which had also gone comprehensive, but

retained a higher reputation for an interest in academic standards. The county council further stimulated this trend by announc- ing three times, as parents debated where to send their children, that it was going to close St Aidan's down. The school now has fewer than 500 pupils — fewer than the old High School days — rattling around the optimistic extensions of the Seventies.

Eighteen months ago a new headmaster, David Kemp, a Newcastle man with de- grees from Edinburgh and Toronto univer- sities, was promoted at St Aidan's: his task, to attract pupils back by appealing to parents. St Aidan's Comprehensive is now, despite much obstruction from above, cal- led 'St Aidan's County High School'. The pupils wear a compulsory navy-blue uni- form. There is an awards ceremony which celebrates academic and non-academic achievements. The headmaster wears — oh horror! — a gown at assembly. The old girls' High School boards, boasting of scholarships, have been retrieved from the cellars where they have lain for 20 years, polished, mended, and re-hung in the old hall. New boards bear the names of the academic achievements of St Aidan's pupils — those who went on to gain firsts at university or came top in the county in their A-level results. The school's prospec- tus boasts that it still teaches Latin and sends pupils to Oxbridge — particularly to Downing College, Cambridge, Last week, their minds wonderfully con- centrated by the hung Cumbria County Council's latest decision to abolish the place, the parents of St Aidan's pupils voted by a 97 per cent majority to opt out of county council control and give power into the school's own hands. This time democracy has been extended downwards. So far 114 schools in the country have opted out, and 60 more are likely to ballot soon. St Aidan's fate now lies with the Secretary of State. The teachers and the pupils I spoke to support the parents, decision. They do not want to return to the old selective system, but they would like a chance to give themselves a future which will meet the requirements of their pupils and their parents, and one free from political interference. The place has plenty to work on in pursuit of future excellence: a large sixth form, three computer rooms, technical teaching facilities, laboratories, a swimming pool, its own studies centre in Langdale in the Lake District, a language laboratory, committed teachers, small clas- ses, and an application from a polytechnic in another town to use some of its spare space to teach degree courses.

'I wonder what we'll call ourselves?' the headmaster mused, as we stood outside the old Sixties front entrance. 'Maybe Carlisle and County High School.' Time will tell, I hoped in 1970, as I grieved over the destruction of what I thought was valuable, as well as plenty which needed improve- ment, and time, indeed, has told.

Previous page

Previous page