Cinema

The Field ('12', Curzon West End)

Heavily underlined

Gabriele Annan

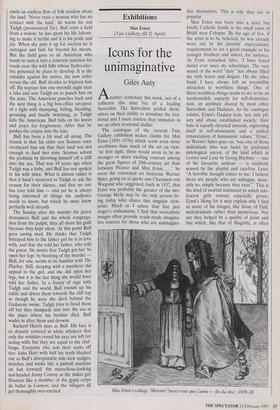

The Field is an Irish film produced by Noel Pearson and written and directed by Jim Sheridan. These two made the success- ful and bernedalled My Left Foot. That was a one-off story. The Field is the opposite: based on a stage play by John B. Keane, it aims for universality. As one of the charac- ters remarks, it goes 'deep — deeper than you think', and underlines its intention as heavily and frequently as Queen Victoria underlined words in her letters. It also deliberately evokes comparison with clas- sics like King Lear and The Playboy of the Western World by quoting from their themes.

The setting is Connemara before the first world war, and it looks as magnificent as the Irish Tourist Board could wish. The main theme is the peasants' love of the land, which became intensified to a condi- tion of land hunger in the 19th century when thousands were driven off it. The vil- lage priest is at hand with lecturettes on Irish history; he delivers the one on the potato famine over an oyster lunch, in case you miss the point. The Lear-like hero is an excitable old fanner, Bull McCabe, who

emits an endless flow of folk wisdom about the land. 'Never trust a woman who has no contact with the land,' he warns his son Tadgh (pronounced Tie). Bull rents a field from a widow; he has spent his life labour- ing to make it fertile and it is his pride and joy. When she puts it up for auction he is outraged and bids far beyond his means. But the field goes to an American who wants to turn it into a concrete junction for roads over the wild hills whose hydro-elec- tric potential he plans to develop. It is the outsider against the native, the new order versus the old. Bull decides to frighten him off. He waylays him one moonlit night near a lake and sets Tadgh on to punch him on the nose. The American punches back and the next thing is a big box-office set-piece of a fight with thumping, falling, bleeding, groaning and finally twitching, as Tadgh kills the American. Bull falls on his knees and prays for forgiveness. After that he pushes the corpse into the lake. Bull has been a bit mad all along. The reason is that his elder son Seamus once overheard him say that their land was not enough to feed two sons. Seamus solved the problem by throwing himself off a cliff into the sea. That was 18 years ago when Tadgh was a baby, and Bull has not spoken to his wife since. What is almost odder is that it hasn't occurred to Tadgh to ask the reason for their silence, and that no one has ever told him — and yet he is always being informed of things the audience needs to know, but which he must know perfectly well already.

The Sunday after the murder the priest denounces Bull and the whole congrega- tion from the pulpit; they all share his guilt because they kept silent. At this point Bull goes raving mad. He thinks that Tadgh betrayed him to the tinker girl he is in love with, and that she told her father, who told the priest. He insists that Tadgh got her 'to open her legs' by boasting of the murder — Bull, for one, seems to be familiar with The Playboy. Still, sleeping with a murderer did appeal to the girl, and she did open her legs, but it is the last thing she would have told her father. In a frenzy of rage with Tadgh and the world, Bull rounds up his cattle and drives them towards the cliff top as though he were the devil behind the Gadarene swine: Tadgh tries to head them off but they stampede him into the sea at the place where his brother died. Bull wades in after them and drowns.

Richard Harris stars as Bull. His face is so densely covered in white whiskers that only the wrinkles round his eyes are left for acting with; but they are equal to the chal- lenge. Everyone else acts their socks off too: John Hurt with half his teeth blacked out as Bull's disreputable side-kick nudges, twitches and winks like a pinball machine on fast forward; the marvellous-looking red-headed Jenny Conroy as the tinker girl flounces like a member of the gypsy corps de ballet in Carmen; and the villagers all get thoroughly over-excited.

Previous page

Previous page