Exhibitions

Max Ernst (Tate Gallery, till 21 April)

Icons for the unimaginative

Giles Auty

Anattier centenary this week, not of a collector this time but of a leading Surrealist. The Surrealists prided them- selves on their ability to stimulate the irra- tional and I must confess they stimulate in me an often irrational dislike.

The catalogue of the current Tate Gallery exhibition makes claims for Max Ernst (1891-1976) which seem even more overblown than much of the art on view. 'At first sight, there would seem to be no stronger or more exciting contrast among the great figures of 20th-century art than between Picasso and Max Ernst. . . .' So avers the renowned art historian Werner Spies, going on to quote one Charrnion von Wiegand who suggested, back in 1937, that Ernst was probably the greater of the two. George Melly may be the only person liv- ing today who shares this singular view- point. Much as I salute that fine jazz singer's enthusiasm, I find that surrealistic images often provide ready-made imagina- tive sources for those who are unimagina-

live themselves. This is why they are so popular.

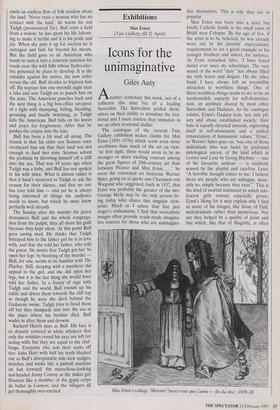

Max Ernst was born into a strict but kindly Catholic family in the small town of Briihl near Cologne. By the age of five, if the artist is to he believed, he was already worn out by his parents' expectations: requirements to set a good example to his younger brothers and sisters, for instance. As Ernst remarked later, 'I have hated duties ever since my schooldays. The very sound of the word "duty" has always filled me with terror and disgust. On the other hand, I have always felt an irresistible attraction to worthless things.' One of these worthless things seems to me to be an inexhaustible capacity for self-dramatisa- tion, an attribute shared by most other Surrealists and Dadaists. As the catalogue relates, Ernst's Dadaist texts 'not only pil- lory and abuse established society; their hate is equally directed inwards, expressing itself in self-abasement and a radical renunciation of humanistic values."Ernst', so Werner Spies goes on, 'was one of those individuals who was beset by profound ontological unrest, of the kind which in Leonce und Lena by Georg Buchner — one of his favourite authors — is suddenly sensed by the playful and carefree Lena: "A horrible thought comes to me: I believe there are people who are unhappy, incur- ably so, simply because they exist".' This is the kind of morbid sentiment to which ado- lescent girls remain especially prone; Ernst's liking for it may explain why I find so many of his images, like those of Dali, melodramatic rather than mysterious. Nor are they helped by a quality of paint and line which, like that of Magritte, is often Max Ernst's collage, Monstre! Savez-vous que j'aime — fin du reve; 1929-30 stiff and unconfident. Early de Chirico was better in these and other respects; his drama was more haunting because less the- atrical. I realise here that while a great deal of Surrealist painting may strike me as exhibitionistic or arbitrary, it may impress others for very similar reasons. To this day, many people of intellectual bent continue to believe in the superiority of the subcon- scious and irrational to the conscious and rational. Clearly, logic is seldom a promin- ent component of their reasoning.

With whom may we compare Ernst? Werner Spies, who edited the catalogue and selected the exhibition, hits on Goya, to my mind unwisely. For Goya's 'black paintings' are anything but irrational. Often they treat the myths and folk memories of the Spanish nation. Their metaphysical allusions are thus of very widespread, rather than purely individual, interest.

Even Ernst's collages, which are general- ly wittier and more disturbing than his paintings, have a strong element of self- conscious cleverness which is the antithesis of anything found in Goya. Goya's 'black paintings', like those of William Blake and other great visionaries, remain true to a consistent internal logic. They employ a metaphysical language but never do so arbitrarily or irrationally. By contrast, Ernst's visionary images tend to look more profound than they are. Their author remained stoically enigmatic when asked for explanations.

Ernst's recourse to the mechanical pro- cesses of lfrottage' and `grattage% something akin to brass-rubbing, as starting-points for his semi-random psychic journeyings reveals some of the strain the artist endured in calling upon himself to be end- lessly imaginative. Where Picasso was intu- itive and pictorial, Ernst was calculating and almost narrative, at times, in his graph- ic conceptions. This, again, distanced him from a superior artist such as Paul Klee who resembled Ernst only in the whimsical- ity of his titles.

I have little doubt the current exhibition of Ernst's work will enjoy great popular success. Luckily my job is to comment on other aspects.

Previous page

Previous page