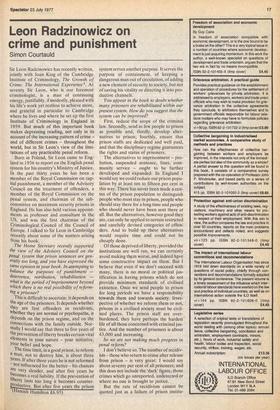

Leon Radzinowicz on crime and punishment

Simon Courtauld

Sir Leon Radzinowicz has recently written, jointly with Joan King of the Cambridge Institute of Criminology, The Growth of Crime: The International Experience*. At seventy Sir Leon, who is our foremost criminologist, is a man of continuing energy, justifiably, if modestly, pleased with his life's work yet restless to.achieve more, and grateful in particular to Cambridge where he lives and where he set up the first Institute of Criminology in England in 1959. But much of this important book makes depressing reading, not only in its account of the increasing pattern of crime and of different crimes throughout the world, but in Sir Leon's view of the limitations of any practicable penal reform.

Born in Poland, Sir Leon came to England in 1936 to report on the English penal system for his country's Ministry of Justice. In the past thirty years he has been a member of the Royal Commission on capital punishment, a member of the Advisory Council on the treatment of offenders, a member of the 'Royal Commission on the Penal system, and chairman of the subcommittee on maximum security prisons in England. He has also held various appointments as professor and consultant in the US, and was the first chairman of the Criminological Council of the Council of Europe. I talked to Sir Leon in Cambridge recently about some of the matters arising from his book.

The Home Secretary recently supported the view of the Advisory Council on the Penal system that prison sentences are generally too long, and you have expressed the same opinion in your book, In attempting to balance the purposes of punishment — deterrence, retribution, rehabilitation — What is the period of imprisonment beyond Which there is no real possibility of reforming a prisoner?

This is difficult to ascertain: it depends on the age of the prisoners. It depends whether they are first offenders or recidivists, Whether they are normal or psychopaths, it depends on the prison regime, and 'on the Connections with the family outside. Normally I would say that three to five years of the prevention of liberty breaks certain vital elements in your nature your initiative, your belief and hope.

The time limit, in a good prison, to reform a man, not to destroy him, is about three Years. If after three years he is not reformed not influenced for the better his chances re very slender, and after five years he rcomes a real liability. If the prevention of iberty lasts too long it becomes co unterZ2ductive. But after five years the prison *(Ilannish Hamilton £6.95)

system serves another purpose. It serves the purpose of containment, of keeping a dangerous man out of circulation, of adding a new element of security to society, but not of saving his vitality or directing it into productive channels.

You appear in the book to doubt whether many prisoners are rehabilitated within our present system. How do you suggest that the system can be improved?

First, reduce the scope of the criminal law. Secondly, send as few people to prison as possible and, thirdly, develop alternatives to prison; fourthly, ensure that prison staffs are dedicated and well paid, and that the disciplinary regime guarantees the rights and status of prisoners.

The alternatives to imprisonment probation, suspended sentence, fines, community service ought to be further developed and expanded. In England I would say we could reduce our prison population by at least ten to fifteen per cent in this way. There has never been made a census of the prison population to distinguish people who must stay in prison, people who should stay there for a long time and people who should never have been sent there at all. But the alternatives, however good they are, can only be applied to certain restricted and carefully devised categories of offenders. And to build up these alternatives would require time and could not be cheaply done.

Of those deprived of liberty, provided the institutions are well run, we can certainly avoid making them worse, and indeed have some constructive impact on them. But I believe that even if we don't succeed with many, there is no moral or political justification in having prisons which do not provide minimum standards of civilised existence. Once we send people to prison for long periods we have a responsibility towards them and towards society. Irrespective of whether we reform them or not, prisons in a civilised society must be civilised places. The prison staff are overburdened, they have perhaps the hardest life of all those concerned with criminal justice. And the number of prisoners is about 43,000 and increasing.

So we are not making much progress in penal reform?

, I don't believe so. The number of recidivists those who return to crime after release from prison is very great: I Would say about seventy per cent of all prisoners; and this does not include the 'dark' figure, those crimes which go unreported, undetected or where no one is brought to justice.

But the rate of recidivism cannot be quoted just as a failure of prison institu

tions, but also as evidence that once you have become a prisoner, it is extremely difficult to readjust yourself to society. It is not fair to blame the prison authorities for the rate of recidivism because it depends also on the conditions in which a man finds himself after he has left prison. The after-care service in this country is virtually nonexistent; but how much is society prepared to pay for after-care? While resources are limited, I am afraid that penal reform will always occupy the last place in the long queue of social priorities.

It was announced last month that a Royal Commission on criminal procedure is being established. Do you think it right that there is no formal limit on how long a suspect may be detained for questioning by the police, and • that the suspect has no right to demand a lawyer at this time?

No. I think he should have the right to a lawyer, also that forty-eight hours is quite long enough for questioning a suspect. After that time a magistrate should decide whether a further period is justified. But in general I am in favour of the liberal character of our criminal procedure which gives the accused the benefit of the doubt. I am not worried, as Sir Robert Mark was, that some guilty men are acquitted. But I am worried that not enough criminals are caught.

Are you attracted by the Scottish system of public prosecutors unconnected with the police?

I am in favour of a radical change — our English system is messy, it assigns to the police a schizophrenic role and keeps them from more important duties. The role of the police is the maintenance of public law and order, the prevention and detection of crime. The prosecution ought to be the business of public prosecutors, not subjugated to the state, of course, but operating within an enlarged DPP's office. I think we may see this reform take place, but only if it has the support of both major political parties.

You mention in the book the falling apart ofsociety in Berlin after the last warm one of the major causes of the increase in crime there. Do you think that in England the increase in crime is attributable to some extent to a deterioration of some aspects of society, what you have called the pressures and conflicts in socuil organisation?

It is an indicator of a weak society, weakened not only economically, but also by sociological and psychological forces. A weakening of religious beliefs, a weakening of the texture of the family. There are greater expectations and temptations to commit crime. Criminals have become more mobile and more intelligent. We are also a more affluent society, and so we do not report a number of crimes because we say it doesn't matter.

I would say that the 'dark' figure of crime in England is now sixty-five per cent of the total crime committed, and that while both recorded and unrecorded crime has increased recently, I believe that the 'dark' figure has gone up at a faster rate. The increase relates primarily to what my great professor Enrico Ferri called the criminalita naturale: crimes against the person, against property, against sex, and against the state.

But isn't the increase also attributable to the growth of crimes, in particular some of the more modern, so-called victimless crimes?

This category has been overstated. Of course there has been an increase, but I would make two points: first, I deny that they are victimless; there is always a victim, who may suffer morally, if not physically. Secondly, the application of the criminal law to some of these crimes — pornography, drugs, etc., — should be considerably reduced. There is much more white-collar crime than we wish to admit — which inquiries like Poulson have only touched on — but it is the criminalha naturale which shows the most dramatic increase.

The immigrants have made a contribution here. It is in the second generation, which does not have the home of their fathers and which has not yet acquired the home of the country of adoption, that there is the highest incidence of crime. And the trouble is that the symptoms I have mentioned, against the background of a country economically weak, mean that we don't have enough money to expand the machinery of justice to keep pace with the expansion of crime, nor to strengthen our community resources.

Going back to your reference to Berlin after the war I would say that Italy is a case of a country in which society is disintegrating. There is a combination of symptoms and an increase in some forms of crime which is particularly disturbing. Kidnapping is carried out in a way which, in my opinion, cannot always be done by the kidnappers without the help of the police. There is always violence in Italy, but now it is ugly violence. There is an enormous amount of theft; also a form of organised crime on a very large scale, of white collar crime, corruption and bribery at all levels of Italian society. In my opinion the 'dark' figure of crime in Italy today is ninety-five per cent. I believe that what comes today into the open in Italy is no more than five per cent of the reality.

The police is in a state of sfrong political division, and the Department of Justice has really lost control. In addition, the prisons are in a terrible state, plus an extraordinary number of escapes, so high, so frequent, that they could only occur with the collaboration of some prison officials. There is also the very active role of the Mafia, which today is much more violent among the young, generation of Mafiosi. Put together all these elements in Italy — the state of crime and the apparatus of criminal justice — and this is, in my view, the state of a disintegrating society.

In many ways your book is a pessimistic one. You do not appear to anticipate great progress in penal reform, nor in reducing the crime rate in England.

When the Borstal system was set up it had a seventy per cent success rate: seven out of ten young offenders stopped committing crime and the Borstal was an object of admiration and envy throughout the world. The view was expressed by many, me included, that the system was working so well that we could expand it in relation to the prison system. But today the proportion has been reversed. It is not that seventy per cent abstain from crime, but that seventy to eighty per cent now return to crime.

I can only indicate a few reasons for this: there is never one reason in social or political argument. The young criminals of today have become tougher than their predecessors forty years ago, and the proportion of young offenders who take drugs today has considerably increased. The Borstal system was born in a unified homogeneous society with strong moral values. So my book is pessimistic in a sense: I cannot see many prisoners being reformed, nor can I see a falling crime rate.

But no criminals have ever succeeded in destroying society. Countries are not destroyed by crime, they are destroyed by their own economic, social and moral structure. And crime becomes just another element in the disintegration. In Italy it is not that crime has disintegrated society: it is society which is in the process of disintegration. Secondly, I believe that we may tend to exaggerate the problem of crime. I can't walk in Central Park, I can't even walk in Fifth Avenue after dark. It is irritating. I don't believe that I would have the courage today to walk through Hyde Park from my club at two o'clock in the morning. We don't seem to enjoy the same sense of freedom, this is perfectly true. But relatively speaking it is still a tiny minority who commit crime.

However, there is an urgent need for us to strengthen our traditional forces of protection against crime. I believe that as we have abolished capital punishment, as our System of probation is used on a quite extensive scale, as the 'dark' figure continues to be a very formidable problem, and the opportunities to commit crime are very great, as our prison system cannot reform many, as our after-care is virtually nonexistent, it is vitally important to strengthen What we call the conventional protections, because we know we cannot introduce changes in society which per se will reduce crime.

Changes in social policy are justifiable on the grounds of justice, wisdom and collective cohesion. But not necessarily as a preventative of crime.What does progress mean in a new society? It has been said that some of the developing countries, once they had thrown off the deadly weight of English imperialism, would carry the banner of social and political progress. Of all the 'developing' countries — according to my statistics — at least ninety per cent have reintroduced capital punishment, often carried out in hideous circumstances. I am afraid that, in the world as a whole, it is a grim Picture.

Previous page

Previous page