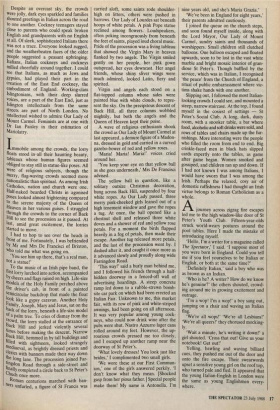

COCKNEY WOPS

Roy Kerridge joins

Little Italy as it celebrates itself

A FEW weeks ago, our local community centre and dance-hall were hired by an Italian social club. As usual, the man from the council forgot to unlock the hall. Like the Trinidadians of the week before, the Italians were left to mill about in the street for hours. Big silver-haired men in hats grew anxious, then wrathful, then held a noisy council of war. Diplomatically, the women took their English-speaking chil- dren into the nearby playground. Night found the Italians, shouting angrily, still outside the hall. While taking the dog Paisley for a late-night walk, I looked up to see lounging Italian youths sneering at me. They looked exactly like delinquents in an American film. (`High School Breakout, Starring Johnny Rocco'), lolling against posts with thumbs hooked into their gla- diator belts. Insults in an unknown but cutting tongue caused Paisley's hackles to rise, but I hung firmly onto his lead. The forcefulness of these Italians impressed me, but they were no match for Brent Council. By dawn, the last of them had vanished.

With Italians on my mind, it was no great surprise a few days later to receive a pamphlet from the London Borough of Islington: 'Little Italy — the Italians in Clerkenwell.' I read on with interest.

In the 19th century an area bounded by Farringdon Road, Mount Pleasant and Cler- kenwell Road came to be known as 'Little Italy'. By 1861 there were over 700 people of Italian birth living in this community. . . . Most of them worked as hawkers or street entertainers, while others made their own ice cream which they sold from barrows in the street. . . . Organ-grinding was a popular way of earning a living, and many of these street entertainers were based in Saffron Hill. . . . The spiritual hub of Little Italy was St Peter's Church on Clerkenwell Road. . . . An important event in the church calendar is the July festival in honour of Our Lady of Cannel. This dates back to 1883 when the first Roman Catholic procession since the Reformation was held in London.

Eager for a glimpse of what London might have been like if the Reformation had never occurred, I took the Tube to Farringdon Road last Sunday. Looking up towards Clerkenwell, I could see crowds thronging the pavements. Balloon vendors walked up and down below their floating wares.

The procession had not yet started when I arrived. Lorries with floats stood among wall-to-wall crowds outside the Italian church. The church (built in 1863) forms part of a vast block, including Italian cafés, shops and tenements, facing Clerkenwell Road and stretching down steep Back Hill. A coach outside the door bore a roughly- painted placard 'Birmingham' in the front window. Italian exiles from far and wide had come to Clerkenwell to meet one another and to venerate Our Lady of Mount Cannel.

Scripture experts (such as Bertie Woos- ter) will know that Mount Carmel, in Syria, is the spot where Elijah challenged the prophets of Baal to call down heavenly fire on a sacrificial pyre. Elijah and his God won, but Mark Twain accuses him of cheating by using petrol instead of water. Roman Catholicism is a mystery to me, so I don't know how Our Lady of Mount Carmel got her name. `She comes from a mountain in France', a programme-seller told me. Despite an overcast sky, the crowds were jolly, dark eyes sparkled and families shouted greetings in Italian across the road to one another. Cockney teenagers stayed close to parents who could speak broken English and grandparents with no English at all. Of sleek, sophisticated Italians there was not a trace. Everyone looked rugged, and the weatherbeaten faces of the older People suggested a peasant upbringing. Italians, Italian cockneys and cockneys milled cheerfully around together. I could see that Italians, as much as Jews and gypsies, had played their part in the creation of the East End cockney, the embodiment of England. Working-class Islingtonians, with their deep slurred voices, are a part of the East End, just as Islington intellectuals from the same streets are part of North London. No intellectual wished to admire Our Lady of Mount Cannel. Feminists are at one with Dr Ian Paisley in their estimation of Mariolatry.

Immobile among the crowds, the lorry floats stood in-all their haunting beauty, tableaux whose human figures seemed obliged to stay still in statue-like poses. All were of religious subjects, though the merry, flag-waving crowds seemed more nationalistic than spiritual. As among Irish Catholics, nation and church were one. Half-naked bearded Christs in agonised Poses looked almost frightening compared to the serene majesty of the Queen of Heaven in her various guises. I struggled through the crowds to the corner of Back Hill to see the procession as it passed. At last, amid great excitement, the lorries started to move.

I had to hop to see over the heads in front of me. Fortunately, I was befriended by Mr and Mrs De Francisci of Brixton, Who told me what was going on. `You see him up there, that's a real man, not a statue!'

To the music of an Irish pipe band, the first lorry lurched into action, accompanied by cheers and flags raised on high. Life-size models of the Holy Family perched above the driver's cab, in front of a painted semicircular backdrop that made the float look like a gypsy caravan. Another Holy ,P_atoilY, Joseph, Mary and Jesus, sat on the back of the lorry, beneath a life-size model of a palm tree. To cries of dismay from the crowd, the lorry stalled at the entrance of Back Hill and jerked violently several times before making the descent. Narrow hack Hill, hemmed in by tall buildings and filled with sightseers, looked strangely Mediaeval, as brightly dressed priests and clerics with banners made their way down the long lane. The procession joined Far- lingdon Road through a side-street and finally completed a circle back to St Peter's Chuch once more. Roman centurions marched with ban- ners unfurled, a figure of St Francis was carried aloft, some saints rode shoulder- high on litters, others were pushed in barrows. Our Lady of Lourdes sat beneath hoops of white petals. A pink Pope statue reclined among flowers. Loudspeakers, often poking incongruously from beneath the feet of saints, played loud choral music. Pride of the procession was a living tableau that showed the Virgin Mary in heaven flanked by two angels. The Virgin smiled gently on her people, her pink gown outspread, her eyes downcast. Her angel friends, whose shiny sliver wings were much admired, looked Latin, fiery and spirited.

Virgin and angels each stood on a flat-topped column whose sides were painted blue with white clouds, to repre- sent the sky. On the precipitous descent of Back Hill, all three columns wobbled mightily, but both the angels and the Queen of Heaven kept their poise.

A wave of religious enthusiasm shook the crowd as Our Lady of Mount Cannel at last appeared, a demure figure of a Madon- na, dressed in gold and carried in a curved gazebo-bower of red and yellow roses. `Maria! Maria! Maria!' voices cried around her.

`You keep your eye on that yellow ball as she goes underneath,' Mrs De Francisci advised.

The yellow ball in question, like a solitary outsize Christmas decoration, hung across Back Hill, suspended by four white ropes. As Our Lady passed, three merry pink-cheeked girls leaned out of a high tenement window and gave the ropes a tug. At once, the ball opened like a chestnut shell and released three white doves and a shower of red and yellow rose petals. For a moment the birds flapped heavily in a fog of petals, then made their escape. Another tug released more petals, and the last of the procession went by. I dashed after it, and caught it once more as it advanced slowly and proudly along wide Farringdon Road. `This way!' said a burly man behind me, and I followed his friends through a half- hidden doorway in a fenced-off wall of advertising hoardings. A steep concrete ramp led down to a rubble-strewn bomb- site car park on which had been erected an Italian Fair. Unknown to me, this market fair, with its row of pink and white-striped awnings, had been going on all afternoon. It was very popular among young cock- neys, who could now drink wine after the pubs were shut. Nastro Azzurro lager cans rolled around my feet. However, the up- roarious crowds pressed me too closely, and I escaped up another ramp near the doorway of St Peter's.

`What lovely dresses! You look just like brides,' I complimented two small girls.

'We wore these at our First Commun- ion,' one of the girls answered perkily. 'I don't know what they mean. [Shocked gasp from her pious father.] Special people make them! My name is Antonella, I'm nine years old, and she's Maria Grazia.' `We've been in England for eight years,' their parents admitted cautiously.

I joined the queue on the church steps, and soon found myself inside, along with the Lord Mayor, Our Lady of Mount Cannel, sundry saints and thousands of worshippers. Small children still clutched balloons. One balloon escaped and floated upwards, soon to be lost in the vast white marble and bright mosaic interior of gran- diose St Peter's. Though baffled by the service, which was in Italian, I recognised `the peace' from the Church of England, a ritual of public embarrassment where vic- tims shake hands with one another.

Slipping out, I followed the most Italian- looking crowds I could see, and mounted a steep, narrow staircase. At the top, I found myself in the cosiest of settings — St Peter's Social Club. A long, dark, dusty room, with a snooker table, a bar where food, alcoholic and soft drinks were sold, and rows of tables and chairs made up the fur- nishings. More interesting were the people who filled the room from end to end. Big crinkle-faced men in black hats slipped cards expertly onto the tables, as game after game began. Women smoked and gossiped, and children ran up and down. If I had not known I was among Italians, I would have sworn that I was among the Irish. Perhaps the relaxed, cosy air of domestic raffishness I had thought an Irish virtue belongs to Roman Catholicism as a whole.

Ajourney across zigzag fire escapes led me to the high window-like door of St Peter's Youth Club. Fifteen-year-olds struck world-weary postures around the pool tables. Here I made the mistake of introducing myself.

`Hello, I'm a writer for a magazine called The Spectator,' I said. 'I suppose most of you were born in England. Could you tell me if you feel yourselves to be Italian or English, or both at the same time?'

`Definitely Italian,' said a boy who was as brown as an Indian.

'Who is he? A writer? How do we know he's genuine?' the others shouted, crowd- ing around me in growing excitement and outrage.

'I'm a wop! I'm a wop!' a boy sang out, jumping on a chair and waving an Italian flag.

`We're all wops!"We're all Lesbians!' `We're all queers!' they chorused mocking- ly.

`Wait a minute, he's writing it down!' a girl shouted. 'Cross that out! Give us your notebook! Get out!'

Yelling, bawling and waving billiard cues, they pushed me out of the door and onto the fire escape. Their swearwords upset a sensitive young girl on the roof top, who turned pale and fled. It appeared that the young Italian-English in London were the same as young Englishmen every- where.

Previous page

Previous page