DESTRUCTIVE DISMISSAL

Alasdair Palmer on a case where

unregulated capitalism triumphed over architectural heritage

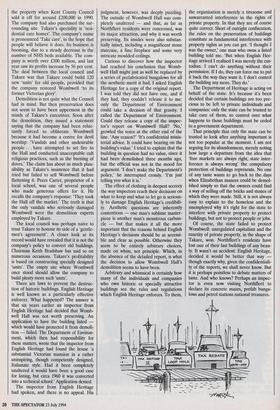

NORTHFLEET in Kent is not noted for its architectural heritage. In terms of beautiful buildings, the appropriate com- parison is with Slough, Croydon and cen- tral Sheffield. Unless you are an aficionado of concrete blocks, glass tow- ers and petrol stations, the overall effect is to make you look for the fastest way out. But there is one exception, and Northflect's inhabitants are particularly proud of it: Wombwell Hall, a large Ital- ianate house designed and built in 1860. 'It's a very special place,' enthuses local historian Anthony Larkin, 'made all the more important to us because of the abysmal quality of the surrounding build- ings. It's like an oasis in a desert.'

Or it was. Wombwell Hall was demol- ished on 2 April this year. Workers from Paddy Ryan, a firm specialising in demoli- tion, arrived at 7 a.m., smashing the locks in order to gain entry. Three and a half hours later, there was nothing left: a flat, open field occupied the space where Wombwell Hall had stood. By the time the local council's Planning Department had been alerted, it was too late for anyone to do anything.

The demolition was ordered by Takare Limited, the company which had bought the property when Kent County Council sold it off for around £200,000 in 1990. The company had also purchased the sur- rounding site. Takare's speciality is 'resi- dential care homes'. The company's name is pronounced 'Take care', in the hope that people will believe it does. Its business is booming, due to a steady decrease in the number of NHS beds available. The com- pany is worth over £300 million, and last year saw its profits increase by 56 per cent. The deal between the local council and Takare was that Takare could build 120 new 'units' for old people, provided that the company restored Wombwell 'to its former Victorian glory'.

Demolition is not quite what the Council had in mind. But then preservation does not seem to have been uppermost in the minds of Takare's executives. Soon after the demolition, they issued a statement saying that the company had been reluc- tantly forced to obliterate Wombwell because it had become a centre for devil worship: 'Vandals and other undesirable people . . . have attempted to set fire to the Hall and conducted unacceptable cult religious practices, such as the burning of doves.' The claim has about as much plau- sibility as Takare's insistence that it had tried but failed to sell Wombwell before flattening it. Peers Carter, proprietor of a local school, was one of several people who made generous offers for it. He recalls the company's response: 'They took the Hall off the market.' The truth is that the only vandals who seriously damaged Wombwell were the demolition experts employed by Takare.

The local council was perhaps naive to trust Takare to honour its side of a `gentle- men's agreement'. A closer look at its record would have revealed that it is not the company's policy to convert old buildings. Chairman Keith Bradshaw has said so on numerous occasions. Takare's profitability is based on constructing specially designed 'units'. The empty site where Wombwell once stood should allow the company to build plenty more such 'units'.

There are laws to prevent the destruc- tion of historic buildings. English Heritage is well known as a particularly effective enforcer. What happened? The answer is that six years earlier an inspector from English Heritage had decided that Womb- well Hall was not worth preserving. An application to have the building listed — which would have protected it from demoli- tion — failed. The Department of Environ- ment, which then had responsibility for these matters, wrote that the inspector from English Heritage had found the house 'a substantial Victorian mansion in a rather uninspiring, though competently designed, ltalianate style. Had it been completely unaltered it would have been a good case for listing, but circa 1960 it was converted into a technical school.' Application denied.

The inspector from English Heritage had spoken, and there is no appeal. His judgment, however, was deeply puzzling. The outside of Wombwell Hall was com- pletely unaltered — and that, as far as Northfleet residents were concerned, was its major attraction, and why it was worth preserving. Its insides were also substan- tially intact, including a magnificent stone staircase, a fine fireplace and some very intricate moulded ceilings.

Curious to discover how the inspector had reached his conclusion that Womb- well Hall might just as well be replaced by a series of prefabricated bungalows for all the aesthetic merit it had, I asked English Heritage for a copy of the original report. I was told they did not have one, and if they had, they couldn't release it to me: only the Department of Environment could take a decision of that gravity. I called the Department of Environment. Could they release a copy of the inspec- tor's report on Wombwell Hail? 'No,' growled the voice at the other end of the line. 'Any reason?' It's confidential minis- terial advice. It could have bearing on the building's value.' I tried to explain that the building in question had no value, since it had been demolished three months ago, but the official was not in the mood for argument. 'I don't make the Department's policy,' he interrupted crossly. 'I'm just telling you what it is.'

The effect of clothing in deepest secrecy the way inspectors reach their decisions on what to keep and what to let go is serious- ly to damage English Heritage's credibili- ty. Aesthetic questions are inherently contentious — one man's sublime master- piece is another man's monstrous carbun- cle — but that makes it all the more important that the reasons behind English Heritage's decisions should be as accessi- ble and clear as possible. Otherwise they seem to be entirely arbitrary choices, made on whim, not principle. Which, in the absence of the detailed report, is what the decision to allow Wombwell Hall's demolition seems to have been.

Arbitrary and whimsical is certainly how many of the individuals and companies who own historic or specially attractive buildings see the rules and regulations which English Heritage enforces. To them, the organisation is merely a tiresome and unwarranted interference in the rights of private property. In that they are of course quite correct. Short of outright confiscation, the rules on the preservation of buildings constitute as fundamental interference with property rights as you can get_ 'I thought I was the owner,' one man who owns a listed building told me. 'But when English Her- itage arrived I realised I was merely the cus- todian. I can't do anything without their permission. If I do, they can force me to put it back the way they want it. I don't control the building any more. They do.'

The Department of Heritage is acting on behalf of the state. It's because it's been decided that certain buildings are too pre- cious to be left to private individuals and companies: only the state can be trusted to take care of them, so control over what happens to those buildings must be ceded to a government department.

That principle that only the state can be trusted to look after anything important is not too popular at the moment. I am not arguing for its abandonment, merely noting how large a departure from the idea that 'free markets are always right, state inter- ference is always wrong' the compulsory protection of buildings represents. No one of any taste wants to go back to the days when Elizabethan manors could be demol- ished simply so that the owners could find a way of selling off the bricks and stones of which they were made. Still, it is not always easy to explain to the homeless and the unemployed why it's right for the state to interfere with private property to protect buildings, but not to protect people or jobs.

Of course, the state failed to protect Wombwell: unregulated capitalism and the sanctity of private property, in the shape of Takare, won. Northfleet's residents have lost one of their last buildings of any beau- ty. It wasn't an accident: English Heritage, decided it would be better that way — though exactly why, given the confidentiali- ty of the reports, we shall never know. But it is perhaps pointless to debate matters of taste. And who knows? Perhaps an inspec- tor is even now visiting Northfleet to declare its concrete mazes, prefab bunga- lows and petrol stations national treasures.

Previous page

Previous page