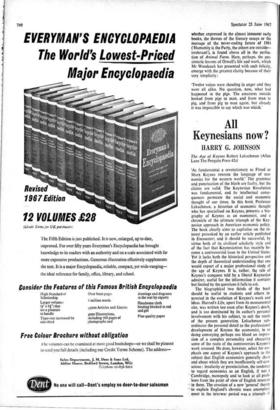

All Keynesians now?

HARRY G. JOHNSON

The Age of Keynes Robert Lekachman (Allen Lane The Penguin Press 42s)

'As fundamental a revolutionary as Freud or Marx Keynes rewrote the language of eco- nomics for the western world.' The grammar and punctuation of the blurb are faulty, but the claims are valid. The Keynesian Revolution was fundamental, and its intellectual conse- quences permeate the social and economic thought of our times. In this book Professor Lekachman, a historian of economic thought who has specialised on Keynes, presents a bio- graphy of Keynes as an economist, and a chronicle of the ultimate triumph of the Key- nesian approach in American economic policy. The book clearly aims to capitalise on the in- terest provoked by an earlier article published in Encounter; and it should be successful, by virtue both of its civilised scholarly style and of the fact that Keynesianism has recently be- come a controversial issue in the United States. Yet it lacks both the historical perspective and the depth of theoretical understanding that one would expect of a major professional study of the age of Keynes. It is, rather, the tale of Keynes's conquest told by a liberal Keynesian admirer, useful for the information it contains but limited by the questions it fails to ask.

The biographical two thirds of the book should be useful to students and others in- terested in the evolution of Keynes's work and ideas. Harrod's Life, apart from its monumental size, was written too soon after Keynes's death, and is too dominated by its author's personal involvement with his subject, to suit the needs of the present generation. Lekachman sub- ordinates the personal detail to the professional development of Keynes the economist, in so doing conveying perhaps too bland an impres- sion of a complex personality and obscuring some of the roots of the controversies Keynes's work aroused. He does, however, select for em- phasis one aspect of Keynes's approach to the subject that English economists generally share and about which they are insufficiently self-con- scious: insularity or provincialism, the tendency to regard economics as an English, if not a Cambridge, monopoly and to look at all prob- lems from the point of view of English interests in them. The creation of a new 'general' theory to explain England's chronic mass unemploy- ment in the interwar period was a triumph oi provincialism; but the legacy of the belief that every new English problem requires a revolu- tionary attack on orthodox theory is largely responsible both for the decline in the prestige of English economics since Keynes's death, and its inability to contribute more to the solution of the country's postwar economic problems.

Lekachman's account of the evolution of Keynes's ideas up to the climax of The General Theory and beyond into war finance and inter- national monetary reform is generally lucid, but can be faulted at two crucial points. First, in his discussion of the- parallel work of Keynes and Robertson in the 1920s, and of the anticipa- tions of The General Theory in the Treatise, he criticises the Treatise for inconsistencies with The General Theory. In so doing, he fails to realise that the essential shift between the Treatise and The General Theory was from the assumption of a fully employed economy in which disturbances affect the general price level, to the assumption of an economy characterised by wage and price rigidity, in which disturb- ances affect the level of output. In the former model, savings can run to waste by being trans- lated into increased consumption induced by a general price reduction instead of into invest- ment; in the latter model savings can run to waste by being translated into reduced con- sumption instead of increased investment. The difference in results involves no inconsistency, but essentially the same logical consequence of the separation of saving and investment /de- cisions, applied to different models of the eco- nomy. Interestingly enough, contemporary monetary theorists have been reverting to the assumptions of the 1920s in their quest for im- proved understanding of monetary phenomena.

Second, The General Theory contains two shots at the new theory, a simple and inaccurate version in which the interest rate is determined entirely by speculators and a more elegant ver- sion in which income, investment, consumption, employment and the rate of interest are jointly determined in a system of general equilibrium relationships. The latter version provided the theoretical appeal of the new theory; but Lekachman presents the simpler faulty version. He is also less clear in handling such concepts as the difference between consumption and in- vestment and the nature of the choice to hold money than a good Keynesian should be.

The later chapters of the biographical sec- tion introduce the second theme of the book, the propagation of Keynesian economics in America. A lengthy chapter shows that the New Deal was by no means a Keynesian exercise, and sketches the contributions of Alvin Hansen in making Keynesian theory teachable and statistically oriented, and in developing the stag- nation thesis. Lekachman also discusses in this section the application of Keynesian economics to war finance, the erroneous forecasts of mas- sive postwar unemployment, and the whittling down of the Full Employment Bill of .1945 into the Employment Act of 1946.

The second section of the book, on The Key- nesian Era,' deals with the main issues of American economic policy in the past decade. Here Lekachman's liberal Keynesianism gets in the way of understanding, by inclining him to espouse the superficial explanations and analysis of the New Frontier. Specifically, he leans to- wards growthmanship, in the process misunder- standing the implications of Denison's study of the sources of us economic growth; he regards automation as a serious threat to employment, though he is forced to admit that there is no evidence in support of this view; and he adopts the 'administered inflation' theory of price in- creases in the 1950s, building on it a case for wage-price policy. He is at his best, however, in chronicling the triumph of Keynesian theory in the tax cuts of 1964 and 1965, and in stating the issue that remains to be resolved, between the conservative Keynesianism of tax reduction and the liberal Keynesianism of enlarged government spending on poverty relief and public services.

The concept of 'the age of Keynes' raises two fundamental issues which Lekacbman discusses only indirectly, or not at all. The first is, how specific can the description be? Granted that Keynes's central message that the level of un- employment can be controlled by economic policy has been learned, how much else of the tone of economic policy in the modern world can be attributed to Keynes? On this question opinions can differ widely; but it is scarcely disputable that the subordination of a whole range of domestic policy objectives to the re- quirements of maintaining a fixed exchange rate, and the imposition of far-reaching inter- ferences with economic freedom in order to safeguard the balance of payments, are contrary to the whole spirit of Keynes's life work.

The second is, how much of a scientific advance did Keynesian economics really repre- sent? Granted that Keynes broke economics free of the mould of reasoning in terms of a barter economy, how superior, if at all, is the Keynesian analytical apparatus to the more traditional quantity theory approach to mone- tary problems? This question has only begun to be explored scientifically, and may take an- other generation to answer; but, thanks to the critical work of Milton Friedman and his fol- lowers, Keynes's own judgment on it can no longer be accepted as final. side of the picture: a native singer who moved the local population to the same sort of hysteria as 'pop' groups in our own day. 'Like an unclean goddess rising from the waves, fore- head villainously low, hollow-eyed, she lived only by .a slight quiver at the knee.'

His observations on the two faces of North Africa in the 'lyrical' essays are reinforced by a striking study of 'The New Mediterranean Culture' in the second part of the book. He refers in it to 'the simultaneously pernicious and inspiring influence of the sea' and of 'this triumphant taste for life, this sense of boredom and the weight of the sun.'

The critical essays cover a wide field, ranging from short reviews of Sartre's first two works of fiction to a twenty-five-page study of Roger Martin du Gard and more general pieces on the future of tragedy and French classicism, He welcomed La Nous& as 'the first cry of an original and vigorous mind whose future works and lessons we await with impatience.' He • criticised Le Mur for what he regarded as gratuitous descriptions of sexuality, but by this time he had decided that Sartre was a great writer. He catches the essence of his work in the last sentence of his review. 'The image, which he perpetuates through his charac- ters, of a man sitting amid the ruins of his life, is a good illustration of the greatness and truth of his work.'

There is ample evidence in these essays of his own blend of tradition and revolt. One is glad to find among them the brilliant essay on the French classic novel called 'Intelligence and the Scaffold.' He detects a family 're- semblance between Madame de La Fayette and Stendhal. 'What gives originality to all novell of this kind,' he writes, 'compared to those

Previous page

Previous page