MONEY AND THE CITY

The Morning Cloud of trade returns

Nicholas Davenport

We live in an age of scandal but the wicked trade figures for May — a deficit on current account of £151 million — would not have been regarded as scandalous if Mr Peter Walker had not lately been crowing about our investment revival and the 'new commercial greatness of Britain ". I gather that Mr Barber has now told him, using the immortal words of At tlee to Professor Laski, that a period of silence on his part would be desirable and that the interpretation of economic statistics had better be left to the heads of the Treasury who know how to cook them up. It is, after all, the job of the head of the Department of Trade and Industry merely to see that British industry is technically equipped to achieve a new period of commercial greatness and everyone knows — from Mr Gilbert Hunt of Chrysler downwards — that new industrial investment is useless unless the workers are prepared to cooperate with management and increase their productivity.

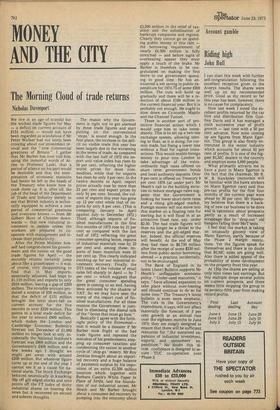

After the Prime Minister himself had congratulated his government and the nation on the good trade figures for April — the monthly returns certainly jump about like a grasshopper — it was, of course, very disappointing to find that in May imports, seasonally adjusted, had leapt to £1,119 million and exports to only £910 million, leaving a gap of £209 million. The invisible account produced a surplus of £58 million, so that the deficit of £151 million brought the total short-fall on current account for the five months to over £320 million. This points to a total trade deficit for the year to around £800 million, which makes the London and Cambridge Economic Bulletin's forecast last December of £1,000 million no longer look so silly. Incidentally the National Institute's forecast was £900 million and the Government's £400 million and a few weeks ago I thought we might get away with around £500 million. But whatever figure turns up at the end of the year I

I cannot see it as a cause for national 'alarm. The Stock Exchange behaved neurotically in knocking 50p off gilt-edged stocks and nine points off the FT index of thirty industrial shares on hearing the news but it recovered on second and soberer thoughts.

The reason why the Government is right not to get alarmed by these trade figures and start putting on the conventional ' stops ' is sound enough. In the first place, the increase in the deficit on visible trade this year has been largely due to the worsening in the terms of trade. As compared with the last half of 1972 the import unit value index has risen by 10 per cent, reflecting the higher world prices for most commodities, while that for exports has risen by only 3 per cent. In the twelve months to April, import prices actually rose by more than 23 per cent and export prices by only 9i per cent. Second, the volume of exports this year has gone up 12 per cent while that of imports by only 6 per cent. (This is comparing January to April against July to December 1972.) Third, although imports of finished manufactures in the first five months of 1973 rose by 21 per cent as compared with the last half of 1972, reflecting the great consumer spending boom, imports of industrial materials rose by 23 per cent and, among these, imports of basic materials were 33 per cent up. This clearly indicated stocking-up for our industrial investment recovery. Finally, the DTI index of the volume of retail sales fell sharply in April — by 7 per cent — which suggests that the great consumer spending spree is coming to an end, having been activated by the shadow of VAT. So we may have seen the worst of the import rush of finished manufactures. For all these reasons the Government is justified in dismissing the dismal talk of the "boom that must go bust ".

Basically I agree with the forthright policy of the Economist— that it would be a disaster if Mr Barber took fright at the bad trade figures and repeated the mistakes of his predecessors, stepping up consumer taxation and condemning the nation to another cycle of ' stop-go ' misery. Mr Roy Jenkins brought about an exportled recovery and a huge balance of payments surplus by his imposition of an extra £2,500 million taxation which, together with Barbara Castle's White Paper In Place of Strife, laid the foundation of our industrial unrest. Mr Heath and Mr Barber brought about a consumer-led recovery by pumping into the economy about £3,500 million in the relief of taxation and the subsidisation of bankrupt companies and regions. Clearly they cannot go on spending public money at this rate — the borrowing requirement of nearly £4,500 million is fully stretched — and before signs of overheating appear they must apply a touch of the brake. Mr Barber is therefore to be congratulated on making the first move to cut government spending in good time. He has announced a net saving in public expenditure for 1974-75 of some £500 million. The cuts will build up gradually and there will be a reduction of about E100 million in the current financial year. But it is probably not enough. He ought to slow down on Ccncorde, Maplin and the Channel Tunnel.

There is another sort of protective financial action which I would urge him to take immediately. This is to set up a two-tier exchange system, allowing sterling to float, as it is doing, for current trade, but fixing a lower rate without a float for capital transactions. This would enable foreign money to pour into London to take advantage of the extraordinarily high rates offered on short term government bonds and local authority deposits. Over 9 per cent is offered on Treasury 9 per cent 1978 (at under par). Mr Heath's call to the building societies to reduce mortgage rates suggests that the Government is looking for lower short-term rates and a rising gilt-edged market. Foreign money will not move into this market on a floating rate for sterling but it will flood in at an attractive fixed rate, say, under $2.50. The bad trade figures will then no longer be a threat to the reserves and the gilt-edged market. Indeed, the official reserves will benefit. At the end of May they had risen to $6,739 million after the receipt of some $330 million from public sector borrowing abroad — a practice, incidentally, not to be encouraged.

The Bank of England in its latest (June) Bulletin supports Mr Heath's unflappable economic policy. "Under-used resources," it says, "have allowed expansion to take place without over-heating and should continue to do so for some time." The Treasury's latest bulletin is even more emphatic. The cuts in the Government's expenditure, it says, will not affect materially the forecast of 5 per cent growth at an annual rate over the eighteen months to June 1974: they are simply designed to ensure that there will be sufficient resources for "the sustained expansion of industrial investment, exports and consumers' expenditure." No doubt this divine confidence is designed to secure TUC co-operation over 'Phase 3.

Previous page

Previous page