ARTS

Exhibitions 1

Tiziano (Doge's Palace, Venice, till 7 October)

From the Alps, with chutzpah

Roderick Conway Morris

This magnificent exhibition of Titian's work is somewhat tentatively pegged to the 500th anniversary of the painter's birth. Tentatively because, despite the compara- tive abundance of documentary evidence for the artist's life and work, his birth date remains uncertain. Titian himself was much to blame for, although he revelled in being an infant prodigy when young, when older he developed the habit of adding a venerable decade or two, styling himself, for example, in an appeal for an injection of cash from Philip II of Spain in 1571, `your servant of 95 years of age', when he was in reality more like 80.

Pieve di Cadore, the mountain village in the Dolomites where Titian was born and spent his early years, had a profound effect on his personality and art. His family was socially respectable but impecunious, and he was sent while still a boy to Venice to learn to be a painter. He was physically robust, hard-working, forthright and not lacking in cunning. He was precocious and Giovanni Bellini took him into his studio. But Bellini, by then the undisputed grand old man of Venetian painting, seems to have disapproved of what he saw as Ti- tian's impetuous and haphazard way of working, and after a time they parted company (not, however, before Titian had to a remarkable degree mastered Bellini's own style).

His other principal mentor was Gior- gione, whose pictures were more naturalis- tic and innovative in the depiction of landscape. Titian — the artist of the first known painting to be entitled simply `Landscape' — was the only major Vene- tian painter to come from the high Alps, and he was clearly intensely interested in mountain scenery, the play of light and shade on rock, woodland, meadow and water, and the sudden changes in weather experienced in these regions, to which he faithfully returned throughout his life. According to Vasari, Titian 'imitated Gior- gione so well that in a short time his works were taken for Giorgione's'. This, and the fact that Titian finished off a number of the other painter's canvases after his untimely death, has posed conundrums for art histo- rians.

While still only in his early twenties, Titian offered his services to the Council of Ten in a letter of consummate chutzpah that sets the tone and modus operandi for his entire career, beginning his submission: 'Having from childhood applied myself to learning the art of painting, not so much through a desire for profit, as to win some little fame . . . and having been urgently sought after by His Holiness the Pope and other great men to go and serve

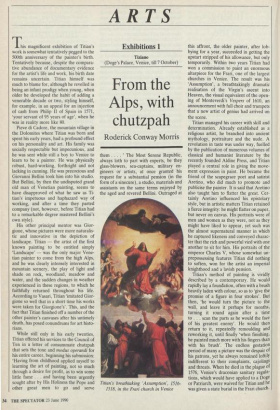

them . . . . ' The Most Serene Republic, always loth to part with experts, be they glass-blowers, sea-captains, military en- gineers or artists, at once granted his request for a substantial pension (in the form of a sinecure), a studio, materials and assistants on the same terms enjoyed by the aged and revered Bellini. Outraged at Titian's breathtaking 'Assumption', 15 16- 1518, in the Fran church in Venice this affront, the older painter, after lob- bying for a year, succeeded in getting the upstart stripped of his allowance, but only temporarily. Within two years Titian had won a commission to paint an enormous altarpiece for the Frani, one of the largest churches in Venice. The result was his `Assumption', a breathtakingly dramatic realisation of the Virgin's ascent into Heaven, the visual equivalent of the open- ing of Monteverdi's Vespers of 1610, an announcement with full choir and trumpets that a new artist of genius had arrived on the scene.

Titian managed his career with skill and determination. Already established as a religious artist, he branched into ancient mythology, portraiture and the nude. A revolution in taste was under way, fuelled by the publication of numerous volumes of classical and humanist literature by the recently founded Aldine Press, and Titian played a central role in giving the move- ment expression in paint. He became the friend of the scapegrace poet and satirist Aretino, who did much to promote and publicise the painter. It is said that Aretino also taught him to flatter the great. Cer- tainly Aretino influenced his epistolary style, but in artistic matters Titian retained a fierce integrity: he might flatter on paper, but never on canvas. His portraits were of men and women as they were, not as they might have liked to appear, yet such was the almost supernatural manner in which he captured likeness and conveyed charac- ter that the rich and powerful vied with one another to sit for him. His portraits of the emperor Charles V, whose somewhat un- prepossessing features Titian did nothing to soften, won for the artist an imperial knighthood and a lavish pension.

Titian's method of painting is vividly described by a contemporary. He would rapidly lay a foundation, often with a brush heavily laden with colour, so as to 'give the promise of a figure in four strokes'. But then, 'he would turn the picture to the wall, and leave it perhaps for months, turning it round again after a time to . . . scan the parts as he would the face of his greatest enemy'. He would then return to it, repeatedly remoulding and reworking it, until finally 'when finishing, he painted much more with his fingers than with his brush'. The endless gestation period of many a picture was the despair of his patrons, yet he always remained loftily indifferent to their complaints, cajolings and threats. When he died in the plague of 1576, Venice's draconian sanitary regula- tions, which would have applied to a Doge or Patriarch, were waived for Titian and he was given a state burial in the Fran church. Titian was perhaps the first artist to achieve truly international celebrity, and the exceptionally wide distribution of his canvases, which he himself strove ceaselessly to ensure, guaranteed his im- mense influence on his successors. If his spirit should revisit the Doge's Palace now, it would no doubt note with satisfaction that pictures have had to be summoned from places as far-flung as Sao Paolo, Leningrad, Naples, New York, Warmin- ster and Washington to realise this admir- able display representing every genre and period of his work.

Previous page

Previous page