Sins of commission

Roderick Conway Morris Venice Biennale Castello Gardens, Arsenale and other venues, until 21 November c 1-lhey order, said I, this matter better in 1 France.' It is the norm at the national pavilions (a record 76 nations are present this year) for a new commissioner to be appointed for each edition, who selects the artist, or artists, to represent their country, or heads a committee that does so. A dozen years ago, France reversed this process, selecting the artist first, who then named their own commissioner.

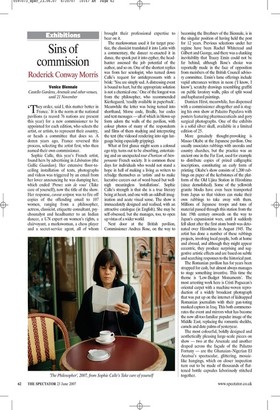

Sophie Calle, this year's French artist, found hers by advertising in Liberation (the Gallic Guardian). Her extensive floor-toceiling installation of texts, photographs and videos was triggered by an email from her lover announcing he was dumping her, which ended Prenez soin de vous' (Take care of yourself), now the title of the show. Her response, caveat scriptot; was to fire off copies of the offending email to 107 women, ranging from a philosopher, actress, classicist, etiquette consultant, psychoanalyst and headhunter to an Indian dancer, a UN expert on women's rights, a clairvoyant, a markswoman, a chess player and a secret-service agent, all of whom brought their professional expertise to bear on it.

The markswoman used it for target practice, the classicist translated it into Latin with a commentary, the dancer re-enacted it in dance, the spook put it into cypher, the headhunter assessed the job potential of the author, and so on. One of the shortest replies was from her sexologist, who turned down Calle's request for antidepressants with a brisk: 'You are simply sad. A distressing event is bound to hurt, but the appropriate solution is not a chemical one.' One of the longest was from the philosopher, who recommended Kierkegaard, 'readily available in paperback'. Meanwhile the letter was being turned into shorthand, Morse code, Braille, bar codes and text messages — all of which in blown-up form adorn the walls of the pavilion, with colour photos of many of the respondents and films of them studying and interpreting the text (the videoed rendering into sign language being especially gripping).

What at first glance might seem a colossal ego trip, turns out to be absorbing, entertaining and an unexpected tour d'horizon of bienpensante French society. It is common these days for individuals who would not stand a hope in hell of making a living as writers to rebadge themselves as 'artists' and to make lucrative careers out of word-based but wellnigh meaningless 'installations'. Sophie Calle's strength is that she is a true literary being at heart, and one with an oddball imagination and acute visual sense. The show is immaculately designed and realised, with an attractive catalogue (in English). She may be self-obsessed, but she manages, too, to open up vistas of a wider world.

Next door at the British pavilion, Commissioner Andrea Rose, on the way to becoming the Brezhnev of the Biennale, is in the singular position of having held the post for 12 years. Previous selections under her regime have been Rachel Whiteread and Gilbert and George, and there was a clunking inevitability that Tracey Emin could not be far behind, although Rose's choice was reportedly made in the face of opposition from members of the British Council advisory committee. Emin's lame offerings include vapid utterances written in neon (I know, I know'), scratchy drawings resembling graffiti on public lavatory walls, piles of split wood and haphazard paintings.

Damien Hirst, meanwhile, has dispensed with a commissioner altogether and is staging his own show at Palazzo Papafava with posters featuring pharmaceuticals and gory surgical photographs. One of the exhibits is a solid silver skull, available in a limited edition of 25.

More genuinely thought-provoking is Masao Okabe at the Japanese pavilion. One usually associates rubbings with anoraks and country churches, but the practice was an ancient one in the Far East, used for example to distribute copies of prized calligraphic inscriptions, constituting an early form of printing. Okabe's show consists of 1,200 rubbings on paper of the kerbstones of the platform of the Old Ujina Station in Hiroshima (since demolished). Some of the yellowish granite blocks have even been transported from Japan so that visitors can make their own rubbings to take away with them. Millions of Japanese troops and tons of material passed through this station from the late 19th century onwards on the way to Japan's expansionist wars, until it suddenly fell silent after the first atom bomb was detonated over Hiroshima in August 1945. The artist has done a number of these rubbings projects, involving local people, both at home and abroad, and although they might appear eccentric, they produce surprising and suggestive artistic effects and are based on subtle and searching responses to the historical past.

The Romanian pavilion has for years been strapped for cash, but almost always manages to stage something inventive. This time the theme is 'Low-Budget Monuments'. The most arresting work here is Cristi Pogacean's oriental carpet with a machine-woven reproduction of a widely broadcast photograph that was put up on the internet of kidnapped Romanian journalists with their gun-toting masked captors in Iraq. This both commemorates the event and mirrors what has become the now all-too-familiar popular image of the Middle East, replacing the romantic sheikhs, camels and date palms of yesteryear.

The most colourful, boldly designed and aesthetically pleasing large-scale pieces on show — two at the Arsenale and another draped across the facade of the Palazzo Fortuny — are the Ghanaian–Nigerian El Anatsui's spectacular, glittering, mosaiclike hangings, which on closer inspection turn out to be made of thousands of flattened bottle capsules laboriously stitched together.

Previous page

Previous page