The magic castle

Elizabeth Jenkins

Windsor Castle In The History of the Nation A. L. Rowse (Weidenfeld and Nicholson £3.95) Or Rowse speaks in this book of the "informed imagination"; that is what his own so eminently is. The phrase at 'first looks like a Paradox; actually it is the two halves of a Perfect whole. There is another pair of opPosites in the constitution of his mind. He Possesses to an unsurpassed degree those qualities which make him understand so deeply, delight in so passionately, architecture, decoration, painting, scenery, the varieties of human genius, so that he has open to hint More sources of ecstatic happiness than most of us can command, yet he seems so often to be saying:

When we are born we cry, that we are corbe To this great stage of fools.

The subject of this book calls out both sides of his nature.

The achievement of the book is that despite the wonderful train of characters who move across the foreground, each evoking his own landscape of associations, despite, too, the tale of architectural development with its hard facts of chalk, cliff, wood, stone, brick and glass, what rises above the book is the vision of the castle itself, an entity made up of thousands of men's work throughout nine hundred years, which yet has an independent Spirit of its own.

Dr Rowse, establishing himself at the Castle, tells or reminds us how many important interviews and famous scenes took place there, scenes known to every reader of history but so often recorded without a mention of their milieu; that King John was in residence there when he was obliged to sign Magna Carta, that it was in the Lists at Windsor that Richard II interrupted the trial by combat between Mowbray and Bolingbroke. He gives a lovely glimpse of the gardens by two young Poets imprisoned in the Castle, King James I of Scotland, who looked down and saw walking in a green plot, enclosed in railings and hawthorne hedges, "the fairest and the freshest younge flower," Joan Beaufort, whom he afterwards married; and the lament of Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, imprisoned by Henry VIII: Where each sweet place returns a taste full sour The large green court where we were wont to rove, With eyes cast up into the maidens' tower, And easy sighs, such as folk draw in love.

Much importance is given to Edward III's inauguration at Windsor of the Order of the Garter, its ceremonial, and to the building of St George's Chapel with its exquisite ironWork signed by the master smith 'Gilebertus' and its stalls for the knights with stall plates inscribed with their coats of arms. The similarity of the building to Eton College Chapel just across the river suggests to Dr Rowse that St George's Chapel was erected by

the Yorkist Edward IV in emulation of the foundation of the Lancastrian Henry VI.

One of the attractions of this book is that, so often, in the series of royal figures, the common-place hit or miss view of character which has hardened into conviction in the public mind, is re-focused by some piece of evidence. The charming sight of Charles II measuring the flow of water under Sir _Samuel Morland's pump by his minute watch, confirms what we know of the king's scientific bent, but Dr Rowse records also his rebuilding of the Royal Lodgings with decorations by Verrio (since pulled down), "the finest work of secular Baroque architecture in England ... Evelyn's unmeasured enthusiasm tells us what contemporary connoisseurs thought of Charles II's work at Windsor, whereas from the history text-books, one would never learn that he built anything."

So with letters from Queen Anne to Lord Oxford, showing such unexpected commonsense: "Now I have a pen in my hand, I cannot help desiring you again when you come next, to speak plainly, lay everything open and hide nothing from me, or how is it possible that I can judge of anything?" Similarly, that George III was a man of much greater mark than common report gives out and that, in fact, the Prince Regent inherited some of his aesthetic gift from his father; and that Queen Victoria's mourning retirement, so sharply criticised then and since, did not mean that she was a recluse; she was in the closest touch with affairs and her system of inviting so many people "to dine and sleep at Windsor" meant merely that her centre of observation was shifted from Buckingham Palace to Windsor Castle.

Rightly, the sovereign who looms largest in a study of Windsor Castle is George IV. The enormous programme of rebuilding he commissioned from Wyatville fell, happily, within the last era when a taste evolved which could vie with the taste of previous centuries. Unlike the heavy, hopeless Victorian version, Wyatville's re-creation of Gothic, though rich, was aerial and fairy-like, with some of the inspiration of the Middle Ages and some indefinable element of the charm of the Regency. The interior decoration of the renovated apartments was George IV's own choice: "The sense of space was increased by mirrors everywhere and pierced or traceried door cases. Cornices were enriched and gilded." A kind of melancholy interest attaches to the fact that the four English monarchs outstanding in their distinction as patrons of art: Henry III, Richard II, Charles I and George IV, were all notorious for their failure as kings.

Other vivid characters appear and disappear like stars: Swift, pining in his cruelly thwarted ambition, giving as the reason for his disappointment:

Swift had the sin of wit, no venial crime!

and Fanny Burney, on the strength of "Evelina," given an appointment in the household of Queen Charlotte and the Princesses. One feels that Dr Rowse is a little unsympathetic towards her; so was her father, so was Lord Melbourne; they all three agree that it was unreasonable of her to feel herself pushed towards a nervous breakdown by never having enough time to herself and by the persecutions of the Queen's odious woman Madame Schwellenborg. Men bear these trials with firmness; women are driven nearly crazy by them. The scenery about the Castle is magically conjured up from lines written about it: Shakespeare's at the end of The Merry Wives of Windsor:

And nightly, meadow-fairies, look you sing • Like to the Garter's compass, in a ring, Th' expressure that it bears, green let it be More fertile-fresh than all the field to see.

another reference, faint but keen, like starlight, to Elizabeth as the FaerieQueene. And from Pope's lines in Windsor Forest:

Here in full light the russet plains extend, There, wrapped in clouds, the bluish hills ascend.

Most effective of all, perhaps, is Lady Lechmere, who says in a letter of 1715, she is surprised that the new king, George I, does not go more often to Windsor: "the Park's so beautiful there."

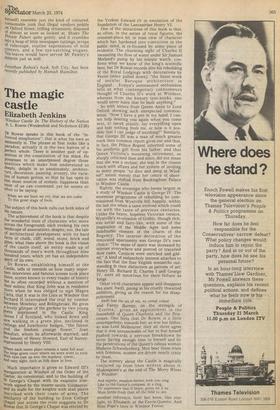

The illustrations are admirable, and beautifully reproduced, the architectural drawings are of great value and charm, and there are fascinating mementos of the royal personages themselves, from the score composed by Henry VIII for his song, "Pastime with Good Company," to a photograph of King George V, the king of one's childhood, riding in Windsor Park with his sons Wales, York, Gloucester and Kent.

Thousands of people will find the book a treasure-chest, and one believes that some, even of those who up till now have found it impossible to forgive Dr Rowse for being himself, will find themselves conciliated by this beautiful work.

Elizabeth Jenkins, the historical biographer and novelist, is currently working on a study of King Arthur.

Previous page

Previous page