BOOKS

How noble in reason

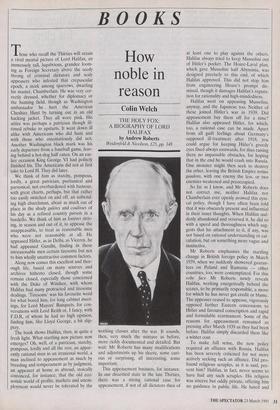

Colin Welch

THE HOLY FOX: A BIOGRAPHY OF LORD HALIFAX by Andrew Roberts

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £25, pp. 348

hose who recall the Thirties will retain a vivid mental picture of Lord Halifax, an Immensely tall, lugubrious, grandee loom- ing as Foreign Secretary above the seedy throng of criminal dictators and scaly appeasers who infested that crepuscular epoch, a stork among sparrows, dwarfing his master, Chamberlain. He was very cor- rectly dressed, whether for diplomacy or the hunting field, though as Washington ambassador he hurt the American Cheshire Hunt by turning out in an old hacking jacket. They all wore pink. His attire was perhaps a patrician though ill- timed rebuke to upstarts. It went down ill alike with Americans who did hunt and with those who ostentatiously did not. Another Washington black mark was his early departure from a baseball game, leav- ing behind a hot-dog half eaten. On an ear- lier occasion King George VI had politely finished his. The Americans did not at first take to Lord H. They did later.

We think of him as starchy, pompous, lordly, a great patrician, puritanical and parsonical, not overburdened with humour, with great charm, perhaps, but that rather too easily switched on and off, an unbend- ing high churchman, about as much out of place in the shady galeres and coulisses of his day as a refined country parson in a bordello. We think of him as forever striv- ing, in season and out of it, to appease the unappeasable, to treat as reasonable men who were not reasonable at all. He appeased Hitler, as in Delhi, as Viceroy, he had appeased Gandhi, finding in these unreasonable men certain tiresome but not to him wholly unattractive common factors.

Along now comes this excellent and thor- ough life, based on many sources and archives hitherto closed, though some remain closed, especially those concerned with the Duke of Windsor, with whom Halifax had many protracted and tiresome dealings. 'Tiresome' was his favourite word for what bored him, for long cabinet meet- ings, for Lord Mayors' Banquets, for con- versations with Lord Reith or, I fancy, with F.D.R, of whom he had no high opinion, finding him, like Lloyd George, a bit slip- pery. The book shows Halifax, then, in quite a fresh light. What startling new picture now emerges? Oh, well, of a patrician, starchy, pompous, lordly and all the rest, an appar- ently rational man in an irrational world, a man inclined to appeasement as much by breeding and temperament as by judgment, an appeaser at home as abroad, stoically convinced, for instance, that the old eco- nomic world of profits, markets and unem- ployment would never be tolerated by the working classes after the war. It sounds, then, very much the mixture as before, more richly documented and detailed. But wait: Mr Roberts has many modifications and adjustments up his sleeve, some curi- ous or surprising, all interesting, some important.

This appeasement business, for instance. In our disarmed state in the late Thirties, there was a strong rational case for appeasement, if not of all dictators then of at least one to play against the others. Halifax always tried to keep Mussolini out of Hitler's pocket. The Hoare-Laval plan, which gave Mussolini half Abyssinia, was designed precisely to this end, of which Halifax approved. This did not stop him from engineering Hoare's prompt dis- missal, though it damages Halifax's reputa- tion for rationality and high-mindedness.

Halifax went on appeasing Mussolini, anyway, and the Japanese too. Neither of these joined Hitler's war in 1939. Did appeasement buy them off for a time? Halifax also appeased Hitler, for which, too, a rational case can be made. Apart from all guilt feelings about Germany's supposed ill-treatment after 1918, you could argue for keeping Hitler's greedy eyes fixed always eastwards, for thus raising there no impassable obstacles, for hoping that in the end he would crash into Russia. One monster might then seek to destroy the other, leaving the British Empire tertius gaudens, with one enemy the less, or two enemies weakened and preoccupied.

So far as I know, and Mr Roberts does not correct me, neither Halifax nor Chamberlain ever openly avowed this cyni- cal policy, though I have often been told that it was obscurely present and influential in their inner thoughts. When Halifax sud- denly abandoned and reversed it, he did so with a speed and thoroughness which sug- gests that his attachment to it, if any, was not based on rational understanding or cal- culation, but on something more vague and instinctive.

Mr Roberts emphasises the startling change in British foreign policy in March 1939, when we suddenly showered guaran- tees on Poland and Rumania — other countries, too, were contemplated. For this volte face Mr Roberts newly reveals Halifax, working energetically behind the scenes, to be primarily responsible, a move for which he has never got credit or blame. The appeaser ceased to appease, vigorously opposed further Eastern concessions to Hitler and favoured conscription and rapid and formidable rearmament. Some of the reasons for appeasement remained as pressing after March 1939 as they had been before. Halifax simply discarded them like a winter coat.

To make full sense, the new policy required an alliance with Russia. Halifax has been severely criticised for not more actively seeking such an alliance. Did pro- found religious scruples, as it is said, pre- vent him? Halifax, in fact, never seems to have had any such scruples. His religion was sincere but oddly private, offering him no guidance in public life. He hated and

feared the Russians, true, but that never stopped him from seeking their help, or, when they perforce became allies, from taking their side against fractious Poles and Baits.

What really scuppered the Russian alliance was not that Halifax sent a low-key delegation in an old slow boat: why not on bicycles?, someone caustically asked. No, it was because, compared with Hitler, we had nothing to offer. Unlike Hitler, we could not give Stalin the Baltic states and half Poland. Why should he settle for less? Without Russia, however, the new policy was a busted flush. As such, it would not commend itself to a wholly rational man, which Mr Roberts often claims Halifax to have been.

Mr Roberts uses 'rational' throughout, as also 'reasonable', in a very British sense, as tending always towards sensible compro- mises and prudent half-measures. Yet fear- less reasoning can surely lead to audacious, unexpected and unorthodox conclusions. It would not so lead someone like Halifax, who once started a sentence, 'I should have thought that one might say that it could be reasonably held that. . . '. Mr Roberts often contrasts Halifax's rationality with Churchill's romanticism, which Halifax ceaselessly strove to restrain. Yet what Halifax restrained was inevitably not romanticism alone, but fiery logic, piercing insights and bold imagination, and he restrained them less by icy rationality than by that grey, impartial caution which domi- nated his life, save in 1939.

In the end, Churchill could presumably stand no more, and packed the old wet blanket off to Washington. The appoint- ment, which Halifax thought 'odious' (he changed his mind later), he and his wife attributed to the machinations of Beaverbrook, primus inter pares of all the sinister crooks by whom Halifax regarded Churchill as surrounded.

When contrasting Halifax's rationality with Churchill's romanticism, moreover, should not one bear in mind Halifax's com- plete and obstinate ignorance of political economy, of which Churchill had, in fact, a sound layman's grasp (doubters of that should re-read his post-war speeches about socialist economics and planning)? Political economy has long been an important part of Western rationality. To lack it altogether is surely to expose oneself to comment on the platform.

I had feared the Washington embassy pages might be dull, formal stuff. In fact, the gradual thawing out of the frozen Halifax, who initially never chatted nor popped nor dropped in as Americans expect, and abhorred the telephone, is hilarious. The process was greatly helped by a Falstaffian Eton friend, Angus McDonnell, who even sang at a stuffy offi- cial dinner a risque ditty, new to me — 'Twenty years a parlour maid in a house of ill repute, Twenty years a parlour maid, and never a substitute'. Perhaps Halifax, chuckling, found in this blameless lady's vicissitudes echoes of his own career.

Humourless? Mr Roberts says so, though he quotes plenty who found him amusing or amused. He adored gossip, too. How so, if not amused by it? Is there such a thing as serious gossip? High-minded? Well, he could be ruthless, as with Sam Hoare, eco- nomical with the truth, and cunning. Not without reason did Churchill call him the Holy Fox. He was not too high-minded to think of bribing French and Italian politi- cians; to smile at the thought of Ciano receiving packets of fivers on the golf course; to think of changing the number- plates on his Rolls when using it unofficial- ly; or to bamboozle the customs. Of all such trifling peccadillos he took a lordly view, treating the rules as if they applied only to the lower orders.

Lordly he certainly was. Hitler he mis- took for a footman, started to hand his coat to him till checked by an appalled Neurath. Senior FO mandarins he treated like upper servants at Garrowby, bidding one to ring up his club and make him a barber's appointment. He was never ovefawed by Churchill, nor was his spirited aristocratic wife, who once ticked Churchill off in a manner to which he was not accustomed. Halifax often gave the impression that he thought Churchill vulgar and ignorant. He nonetheless respected and envied his genius. This he proved when he selflessly sacrificed his own excellent chance of becoming Prime Minister for no other con- vincing reason.

Churchill, too, knew Halifax's worth. He once cruelly said of him, to be sure,`com- pounded of charm. . . no coward, no gen- tleman is, but there is something that runs through him like a yellow streak; grovel, grovel, grovel', to Indians, to Germans, to Americans. Is this what Churchill really thought of Halifax? Mr Roberts is sure it is not. His book will tell you why.

'The scan said it was male, so 1 had a virgin abortion.'

Previous page

Previous page