ARTS

Architecture

Sir Christopher Wren and the Making of St Paul's (Royal Academy, till 12 May)

The submerged cathedral

Alan Powers

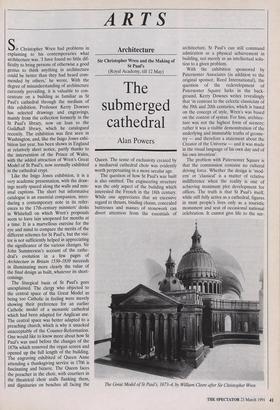

Sir Christopher Wren had problems in explaining to his - contemporaries what architecture was. 'I have found no little dif- ficulty to bring persons of otherwise a good genius to think anything in architecture could be better than they had heard com- mended by others,' he wrote. With the degree of misunderstanding of architecture currently prevailing, it is valuable to con- centrate on a building as familiar as St Paul's cathedral through the medium of this exhibition. Professor Kerry Downes has selected drawings and engravings, mainly from the collection formerly in the St Paul's library, now on loan to the Guildhall library, which he catalogued recently. The exhibition was first seen in Washington, and, like the Inigo Jones exhi- bition last year, has been shown in England at relatively short notice, partly thanks to the intervention of the Prince of Wales, with the added attraction of Wren's Great Model of St Paul's, now normally exhibited in the cathedral crypt.

Like the Inigo Jones exhibition, it is a very academic presentation, with the draw- ings neatly spaced along the walls and min- imal captions. The short but informative catalogue is an essential companion, intro- ducing a contemporary note in its refer- ences to the 17th-century ministers' desks in Whitehall on which Wren's proposals seem to have lain unopened for months at a time. It is a marvellous exercise for the eye and mind to compare the merits of the different schemes for St Paul's, but the visi- tor is not sufficiently helped in appreciating the significance of the various changes. Sir John Summerson's account of the cathe- dral's evolution in a few pages of Architecture in Britain 1530-1830 succeeds in illuminating more clearly the value of the final design as built, whatever its short- comings.

The liturgical basis of St Paul's goes unexplained. The clergy who objected to the central space of the Great Model as being too Catholic in feeling were merely showing their preference for an earlier Catholic model of a monastic cathedral which had been adapted for Anglican use. The central space was better adapted to a preaching church, which is why it smacked unacceptably of the Counter-Reformation. One would like to know more about how St Paul's was used before the changes of the 1870s which removed the organ screen and opened up the full length of the building. The engraving exhibited of Queen Anne attending a thanksgiving service in 1706 is fascinating and bizarre. The Queen faces the preacher in the choir, with courtiers in the theatrical choir stalls flanking them, and dignitaries on benches all facing the Queen. The sense of exclusivity created by a mediaeval cathedral choir was evidently worth perpetuating in a more secular age. The question of how St Paul's was built is also omitted. The engineering structure was the only aspect of the building which interested the French in the 18th century. While one appreciates that an excessive regard to thrusts, binding chains, concealed buttresses and masses of stonework can divert attention from the essentials of architecture, St Paul's can still command admiration as a physical achievement in building, not merely as an intellectual solu- tion to a given problem.

With the exhibition sponsored by Paternoster Associates (in addition to the original sponsor, Reed International), the question of the redevelopment of Paternoster Square lurks in the back- ground. Kerry Downes writes revealingly that 'in contrast to the eclectic classicism of the 19th and 20th centuries, which is based on the concept of style, Wren's was based on the context of syntax. For him, architec- ture was not the highest form of scenery; rather it was a visible demonstration of the underlying and immutable truths of geome- try — and therefore a statement about the Creator of the Universe — and it was made in the visual language of his own day and of his own invention'.

The problem with Paternoster Square is that the commission contains no cultural driving force. Whether the design is 'mod- ern' or 'classical' is a matter of relative indifference when the reality is one of achieving maximum plot development for offices. The truth is that St Paul's itself, while still fully active as a cathedral, figures in most people's lives only as a touristic monument and seat of occasional national celebration. It cannot give life to the sur- The Great Model of St Paul's, 1673-4, by William Cleere after Sir Christopher Wren roundings and create a genuine sense of a cathedral precinct. The modern planning panacea of introducing shops to generate life, with which the new Paternoster devel- opment claims to remedy the defects of the old, will only work if the shops have some- thing interesting to sell, and this virtually depends on low rents and a positive policy towards tenants, as operated in Covent Garden market. Otherwise there will be no reason to visit the place and it could be as nearly dead as it is now. Developments like Hay's Dock and Tobacco Dock show how branches of high street multiples cannot fill out the architectural matrix to achieve town planning by shopping. To pay respect to St Paul's by developing the area in a classical style depends on a more compelling motive for the style than picturesque appropriateness. Lacking this, the existing buildings in their decent bland- ness do less harm to the cathedral than may be expected from the classical propos- als, still to be revealed, which contain a greater area of office space than is current- ly on the site. The stylistic argument has obscured the more fundamental issue of creating a convincing sense of place. We still seem as far removed as Wren's con- temporaries from being able to understand what architecture is and how to get it.

Previous page

Previous page