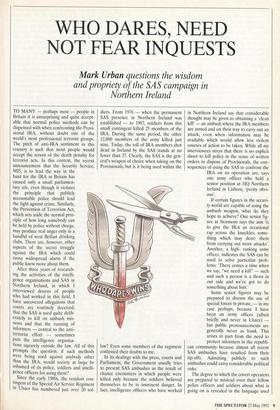

WHO DARES, NEED NOT FEAR INQUESTS

Mark Urban questions the wisdom

and propriety of the SAS campaign in Northern Ireland

TO MANY — perhaps most — people in Britain it is unsurprising and quite accept- able that normal police methods can be dispensed with when confronting the Provi- sional IRA, without doubt one of the world's most professional terrorist groups.

The pitch of anti-IRA sentiment in this country is such that most people would the principle that publicly accountable police should lead the fight against crime. Similarly, the Prevention of Terrorism Act, which sets aside the normal prin- ciple of how long somebody can be held by police without charge, may produce real anger only in a handful of west Belfast drinking clubs. There are, however, other aspects of the secret struggle against the IRA which could cause widespread alarm if the public knew more about them.

After three years of research- ing the activities of the intelli- gence organisations and SAS in Northern Ireland, in which I interviewed dozens of people who had worked in this field, I have uncovered allegations that courts are routinely deceived, that the SAS is used quite delib- erately to kill on ambush mis- sions and that the running of Informers — central to the anti- terrorist effort — sometimes puts the intelligence organisa- tions squarely outside the law. All of this prompts the question: if such methods were being used against anybody other than the IRA, would society at large be ashamed of its police, soldiers and intelli- gence officers for using them?

Since the early 1980s, the resident con- tingent of the Special Air Service Regiment in Ulster has numbered just over 20 sol-

diers. From 1976 — when the permanent SAS presence in Northern Ireland was established — to 1987, soldiers from this small contingent killed 25 members of the IRA. During the same period, the other 12,000 members of the army killed just nine. Today, the toll of IRA members shot dead in Ireland by the SAS stands at no fewer than 37. Clearly, the SAS is the gen- eral's weapon of choice when taking on the Provisionals, but is it being used within the

law? Even some members of the regiment confessed their doubts to me.

In its dealings with the press, courts and Parliament, the Government usually tries to present SAS ambushes as the result of chance encounters in which people were killed only because the soldiers believed themselves to be in imminent danger. In fact, intelligence officers who have worked in Northern Ireland say that considerable thought may be given to obtaining a 'clean kill' — an ambush where the IRA members are armed and on their way to carry out an attack, even when information may be available which would allow less violent courses of action to be taken. While all my interviewees stress that there is no explicit shoot to kill policy in the sense of written orders to dispose of Provisionals, the con- sequences of using the SAS to confront the IRA on an operation are, says one army officer who held a senior position at HQ Northern Ireland in Lisburn, 'pretty obvi- ous'.

If certain figures in the securi- ty world are capable of using the ambush weapon, what do they hope to achieve? One senior fig- ure at Stormont says the aim 'is to give the IRA an occasional rap across the knuckles, some- thing which may deter them from carrying out more attacks'. Another, a high- ranking army officer, indicates the SAS can be used to solve particular prob- lems: 'There comes a time when we say, "we need a kill" — such and such a person is a thorn in our side and we've got to do something about him.'

Some senior figures may be prepared to discuss the use of special forces in private, — in my case perhaps, because I have been an army officer (albeit briefly and never in Ulster) - but public pronouncements are generally never as frank. This arises in part from the need to protect informers in the republi- can community because almost all recent SAS ambushes have resulted from their tip-offs. Admitting publicly to such ambushes could carry considerable political risks.

The degree to which the covert operators are prepared to mislead even their fellow police officers and soldiers about what is going on is revealed in the language used to describe planned confrontations with the Provisionals. In the late 1970s, shortly after it was committed to Northern Ireland, SAS orders referred unambiguously to 'ambush' operations. To a soldier this word means an attack: any prisoners taken are merely survivors of an ambush. Some Royal Ulster Constabulary and army officers questioned the benefits and legality of such operations. These doubts prompted a five-year period (from late 1978 to 1983) in which the SAS were explicitly 'reined in', in the words of one senior Stormont figure, and killed nobody in Ulster.

Following the humiliating failure of the RUC's own special units in a series of fatal incidents late in 1982, the importance of the SAS for ambushes once again emerged. When this happened, the word 'ambush' was dropped from SAS orders and more coded language substituted — notably the term Observation Post/Reactive. This sug- gests a mission to watch the terrorists and react accordingly. According to an SAS man who has served in Northern Ireland, such a mission, abbreviated to 'OP/React', is `to all intents and purposes an ambush' but is not referred to as such in deference to RUC officers who still object to such tactics.

In May 1987, the SAS mounted its biggest ambush against the IRA. Eight Pro- visionals and one passer-by were killed at Loughgall during an attempt to bomb a police station there. The soldiers' orders still referred to an 'OP/React' even though an observation post normally consists of only two or three soldiers and there were up to 40 SAS men deployed in the village with weapons including belt-fed machine guns.

Publicly reconciling an operation like Loughgall with the 1967 Criminal Law Act (Northern Ireland), which states that only reasonable force may be used in the pre- vention of crime, might be a difficult proposition. A senior security forces' offi- cer, who played a key role in the operation, said to me, Was it a decision to kill those people? I don't think it would have been phrased like that. Somebody would have said "how far do we go to remove this group of terrorists?" and the answer would have been "as far as necessary".'

After Loughgall, the intelligence men and soldiers involved retired for a party to celebrate the operation: a successful ambush is regarded by many of those involved as a spectacular success for the security forces. The professional pride of getting a 'result' in the unreliable world of informer intelligence may blind those tak- ing part to the wider implications. One per- son concerned with the Gibraltar shootings, in which three unarmed IRA members were shot by the SAS in 1988, describes it as a 'brilliant intelligence oper- ation' and forcefully rejects the suggestion that it would have been better to take police officers rather than the SAS to carry out arrests. The received wisdom of many covert operators that ambushing the IRA reduces terrorist violence needs to be challenged. Since the Loughgall ambush of 1987, two more IRA members have been killed by the SAS in Loughgall itself and another three members of the east Tyrone IRA killed by them in Coagh last year. Several police stations and Ulster Defence Regi- ment barracks have been destroyed by the local IRA since the 1987 ambush, including the surviving part of the Loughgall RUC station. The IRA's worst loss of recent years seems hardly to have altered matters in that region of Ulster.

While many officers may argue that jail will not deter certain IRA members, it is worth recording that 14 out of 20 IRA men killed by the SAS and 14 Intelligence Com- pany (an elite Army surveillance unit) dur- ing 1983-87 had no criminal record. Even those who believe the SAS should adminis- ter an unofficial brand of capital punish- ment might blanch at the fact that in addition to killing 37 or more IRA mem- bers since 1976, the regiment has also mis- takenly shot dead six uninvolved bystanders in Ulster.

Ministers are not asked to give written approval to SAS ambushes in advance, according to people who have served in senior positions in Ulster. Instead, the Sec- retary of State may be given a vague verbal tip-off by the Chief Constable of the Gen- eral Officer Commanding that an opera- tion is underway. When I asked one senior Stormont figure whether he was not con- cerned about being held responsible for activities over which he had no real control, he replied that he was, but that 'we just tended to hide behind the operational independence of the RUC'.

Changes 12 years ago to the rules for inquest procedures in Northern Ireland mean that soldiers who have carried out ambushes do not have to appear, the court issues no verdict, only a 'finding', and its jury is picked by the police. As a result the security forces are able to indulge in what army officers admitted to me is routine deception of the courts in cases where covert operations are involved. The func- tions of inquest courts have been further restricted by the Crown's practice of delay- ing for years hearings about deaths result- ing from intelligence operations. The

'Bomber Harris was a bit of a Euro-sceptic.'

examples given to me of deception, there- fore, relate to operations in the mid-1980s since inquests have yet to be held on more recent ones. These delays buy vital time for informers but also make it highly unlikely that witnesses who may question the offi- cial version can still be found or that their recollection of these distant events will withstand cross-examination.

In December 1984, SAS soldiers shot dead two IRA men who were on their way to attack a UDR part-timer who worked at the Gransha hospital in Londonderry. An anonymous officer subsequently told an inquest that the presence of plain-clothes troops in the hospital grounds was routine and that the police knew little of the sol- diers' mission. In fact, according to an intelligence officer, the soldiers were there because they had a 'perfect tip-off' that the attack was about to happen and the entire operation was co-ordinated through a police operations centre. In this case, the soldier giving evidence at the inquest sought not just to protect the informer but also to prevent the court from realising that lethal force might not have been necessary because the SAS were acting on high-quali- ty intelligence.

Several months before the Gransha attack, loyalist terrorists tried to kill Gerry Adams, the Sinn Fein leader. Adams was shot several times by three assailants who were subsequently arrested. The Army press office denied that the soldiers who made the arrest were members of the SAS and said their presence near the incident was 'complete coincidence'. This line was maintained during the subsequent trial of the three loyalists. But two senior security forces officers have confirmed to me that the soldiers were indeed SAS and that intelligence officers knew in advance that there was a planned attack on Adams. Deceiving the court may have helped pro- tect an informer, but it also had the very useful effect of preventing people from asking why the intelligence officers had allowed the attack to go ahead and why the SAS had waited until after the loyalists fired before apprehending them.

In February 1985, the SAS shot dead three IRA men in Strabane County, Tyrone. An intelligence officer told me that the soldiers, unseen by the Provisionals, launched an attack without warning. One or two of the IRA men may have survived the initial fusillade and there were allega- tions from local people that the SAS had taken off the Provisionals' balaclava masks to check their identities before giving each at least one shot through the head. Accord- ing to someone who served in a senior position, these claims were taken seriously at Stormont.

Officially, the Government maintained the three had been killed lawfully — and

only after the IRA members had noticed the SAS and turned towards them. Sugges- tions that they had been given coups de grace could not be tested at the inquest

since the Provisionals' clothing had been destroyed by the authorities — although the Crown conceded that their balaclava helmets did not have bullet holes in them. More than 40 spent bullet casings (the SAS fired 117 rounds in the engagement), some of which are believed to have fallen close to the IRA men's bodies, were 'lost' and could never be examined by forensic scien- tists.

Several SAS ambush-type operations have occurred since 1985 — most recently four IRA men were killed in Coalisland in February this year. Since inquests have not taken place for most of these incidents, it is hard to test the Crown's version of events. Two years ago, Tom King, as Secretary of State for Defence, told Parliament that the Government was still using disinformation in its dealings with the press over Ulster to protect lives and for 'absolutely honourable security reasons'. It would appear that a large proportion of these officially sanc- tioned untruths are told to protect the lives of informers.

It is vital for the security forces to main- tain sources in terrorist organisations but doing so involves the agent handlers with people who they may know to be involved in murder. It takes a rare case of a police investigation conducted on the principles followed in Britain to show how far accept- able standards of behaviour have drifted in Ulster.

It was not the RUC but John Stephens, the deputy chief constable of Cam- bridgeshire, investigating possible collusion between the security forces and loyalist ter- rorists, who put the army agent Brian Nel- son in prison earlier this year. Nelson had infiltrated the loyalist Ulster Freedom Fighters on behalf of the Field Research Unit, the Army's informer handling unit. Nelson was actively involved in loyalist ter- rorism: he pleaded guilty to five charges of conspiracy to murder. This made him a prize agent — well paid by the tax-payer for his services — but a liability to the Army in the courtroom.

While there is no alternative to running agents in terrorist organisations — it is the security forces' very failure to penetrate IRA units operating in Britain which means there is so little good intelligence on them — there are several areas where the conduct of the struggle against the IRA might be altered. While the use of ambush- es makes some soldiers and police officers feel better, it may well be illegal, contribute little to improved security and provide the IRA with martyrs. Most seriously, perhaps, if courts are deceived to make such opera- tions possible, the secret elites in Northern Ireland risk doing serious damage to the very institutions which they are sworn to defend.

Mark Urban's book Big Boys' Rules: The Secret Struggle Against the IRA is pub- lished this month by Faber and Faber, price £14.99.

Previous page

Previous page