Architecture

The greening of the valley

Ebbw Vale Garden Festival

Does the land wait the sleeping lord or is the wasted land that very lord who sleeps?

So runs the last of the many rhetorical questions which compose David Jones's poem 'The Sleeping Lord', setting the myth of sleeping Arthur in a context ecological before its time. A visit to the Garden Festi- val Wales in Ebbw Vale raises similar metaphorical and anthropomorphic paral- lels of nationality and landscape. Of all the constituent parts of the United Kingdom, Wales is the most obviously formed by its landscape — grand but intricate, revealing, as Graham Sutherland discovered when painting in Pembrokeshire, a sense of grandeur in small features, and mostly turned against outsiders.

As the road climbs from Newport towards Ebbw Vale, the landscape becomes wilder. Had the coal seams and iron ore deposits not drawn pioneer indus- trialists in the 18th century, this would still be remote and pastoral upland. A small caption somewhere in the Garden Festival directs one's view to the opposite side of the valley, to the highest and most westerly natural beech wood in Britain. Instead, huge industrial communities gathered in this inhospitable climate.

The Garden Festival does not ignore these roots. Indeed it almost answers the questions of the David Jones poem. The sleeping lord has been laid to rest with a blanket of imported topsoil. The land has been given a face-lift, with waterfalls, lakes and rocky outcrops where once were derelict railway lines and slag heaps. High- er up, the British Steel Plate Works remain as the relic of the traditional industry, their vast blue sheds looming against the rows of closely packed houses. But has the sleeping lord, the 'Tutelar of the Place' (to borrow another David Jones title), any recognis- able presence? Has Wales discovered any- thing about itself through the Festival?

It would be unrealistic to expect this question to be answered in architectural terms. None of the previous garden festi- vals has excelled in architecture, and Ebbw Vale contains a mixture of featureless structures recalling industrial estates and others more carefully designed but seldom departing from the formula of the tension roof structure. The timber 'Wetlands and Opencast Discovery Centre' by the upper lake, a survival from an ironmaster's estate, is pleasing and unfussy, but hardly any of the other buildings address the problem of how to build in the country with a sense of locality.

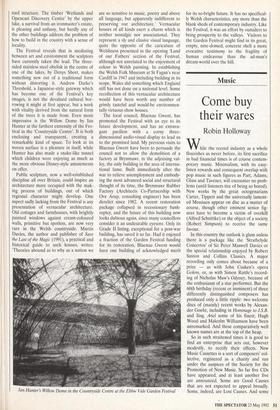

The Festival reveals that in mediating between art and environment the sculptors have currently taken the lead. The three- sided stainless steel obelisk in the centre of one of the lakes, by Denys Short, makes something new out of a traditional form without distorting it. Andrew Darke's Threshold, a Japanese-style gateway which has become one of the Festival's key images, is not the devalued cultural bor- rowing it might at first appear, but a work with vitality derived from the natural form of the trees it is made from. Even more impressive is the Willow Dome by Ian Hunter at the farthest extremity of the Fes- tival in the 'Countryside Centre'. It is both enclosing and transparent, creating a remarkable kind of space. To look at its woven surface is a pleasure in itself, while Hunter has also made a snake-like tunnel which children were enjoying as much as the more obvious Disney-style amusements on offer.

Public sculpture, now a well-established discipline all over Britain, could inspire an architecture more occupied with the mak- ing process of buildings, out of which regional character might develop. One aspect sadly lacking from the Festival is any presentation of vernacular architecture. Old cottages and farmhouses, with brightly painted windows against cream-coloured walls, primitive but spotless, are now very rare in the Welsh countryside. Martin Davies, the author and publisher of Save the Last of the Magic (1991), a practical and historical guide to such houses, writes: 'Theories abound as to why as a nation we

are so sensitive to music, poetry and above all language, but apparently indifferent to preserving our architecture.' Vernacular houses of all kinds exert a charm which is neither nostalgic nor associational. They represent a sly and elusive visual language, quite the opposite of the caricature of Welshness presented in the opening 'Land of our Fathers' section of the Festival, although not unrelated to the enjoyment of colour in Welsh painting. In establishing the Welsh Folk Museum at St Fagan's near Cardiff in 1947 and including building in its scope, Wales did something which England still has not done on a national level. Some recollection of this vernacular architecture would have been worth any number of grimly tasteful and would-be environmen- tally virtuous show houses.

The local council, Blaenau Gwent, has promoted the Festival with an eye to its future development, and has an extrava- gant pavilion with a corny three- dimensional audio-visual display to lead us to the promised land. My previous visits to Blaenau Gwent have been to persuade the council not to allow the demolition of a factory at Brynmawr, in the adjoining val- ley, the only building in the area of interna- tional fame. Built immediately after the war to relieve unemployment and embody- ing the most advanced social and structural thought of its time, the Brynmawr Rubber Factory (Architects Co-Partnership with Ove Arup, consulting engineer) has been derelict since 1982. A recent restoration package collapsed in recessionary bank- ruptcy, and the future of this building now looks dubious again, since many councillors consider it an undesirable eyesore. Only its Grade II listing, exceptional for a post-war building, has saved it so far. Had it enjoyed a fraction of the Garden Festival funding for its restoration, Blaenau Gwent would have one building of acknowledged merit Ian Hunter's Willow Dome in the Countryside Centre at the Ebbw Vale Garden Festival for its so-bright future. It has no specifical- ly Welsh characteristics, any more than the blank sheds of contemporary industry. Like the Festival, it was an effort by outsiders to bring prosperity to the valleys. Visitors to the Garden Festival might find in its great, empty, nine-domed, concrete shell a more evocative testimony to the fragility of human endeavour than the ad-man's dream-world over the hill.

Previous page

Previous page