The Economy

The City and the Labour Government

By NICHOLAS DAVENPORT

THIS is a nerve-testing time for the City. The ad- vent of a Labour Govern- ment had been written up into such a major calamity that a slump in share values of the order of 20 per cent had beeh widely forecast. The subsequent news that Khrushchev had lost control of Russian nuclear physics while Cousins had gained control of British nuclear Physics did nothing to restore confidence in Throgmorton Street. The place became really jittery on Monday when the full Cabinet list became known. But I am sure that second thoughts will bring a calmer atmosphere. The Outstanding calming fact is that with a tiny majority in the House of Commons the Labour Party has to obey its leader implicitly, and that this leader is no revolutionary, but, as the inti- mate broadcast interview revealed, an extremely able pragmatic social reformer pledged to run a mixed economy, but not to implement the socialising Clause Four. No Prime Minister since the war has been better qualified by training and exPerience to deal with the shocking balance of Payments crisis bequeathed by his predecessors. When an industrial company's management is changed for the better the shares usually im- prove in market value.

There are, of course, two good reasons why the share markets should come down after the won- derful 17 per cent rise which they enjoyed be- tween February 3 and October 1. First, investors are naturally nervous about the corrective measures which Mr. Wilson must take to reduce the deficit on the balance of payments, for ttey fear that he may resort to a 6 per cent or 7 per cent Bank rate. I have already expressed the °Pinion that overall deflation in the Thorney-' croft or Selwyn Lloyd manner is definitely out. I cannot see what good a 6 per cent Bank rate Would do. If you want to get, say, $1,500 million for the support of sterling, it is far better and cheaper to get it (as arranged) from the IMF ($1,000 million) and the US Treasury ($500 Million) than to attract 'hot' money to London hy raising interest rates. In either case, the money Will have to be repaid, but the 'hot' money will cost betweep 5 per cent and 6 per cent, while the IMF loan will bear only half that interest charge.

Foreign confidence will be won if the right Measures are taken at home, and these I take to be; (i) a raising of the initial deposit from 20 Per cent to 30 per cent on hire-purchase trans- actions (the total hire-purchase debt, now ex- ceeding £1,000 million, has become dangerously high); (ii) a commercial building licensing scheme; (iii) tighter exchange control over in- vestment abroad; (iv) hab,ring the foreign travel allowances (now £250); (v) temporary tariff sur- charges (or import quotas) on select imports; and (A) some form of tax saving for exporters in order to boost exports. Such measures would go far (0 win the confidence not only of the City but of the banking gnomes of Zurich. Next, there is naturally nervOusness over the tax-reform proposals of the new government. A

corporation tax, a stiffer capital gains tax and a wealth tax are all greatly feared and it will be next April before the reality or unreality of The fear can be brought to light. But here again the anxiety is greatly exaggerated. Mr. Wilson is a reasonable and rational social reformer. He knows perfectly well that he cannot get the trade unions to agree to an incomes policy unless social justice is seen to be done by way of taxation of profit incomes and capital wealth. He himself, it is believed, has moved away from the idea of a dividend tax or a differential profits tax and has come to favour the straight cor- poration tax on the American model. Now it is true that a corporation tax of, say, 50 per cent, could badly hurt companies which have been distributing their profits up to the hilt, but Mr. Wilson will have to justify to the House of Commons that what extra taxation he proposes to exact from companies is fair and reasonable. At the moment income tax has been taking about £1,000 million from companies and profits tax £330 million. I doubt if Mr. Wilson could win par- liamentary support for an extra imposition of more than, say, £200 million.

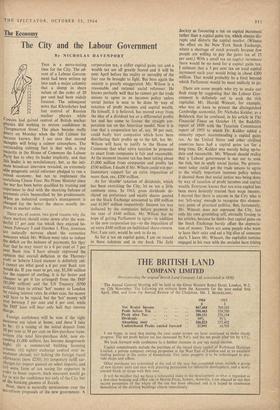

As for 'double' taxation of dividends, whiCh has been exercising the City, let us use a little common sense. In 1963, gross dividends de- clared on preference and equity shares quoted on the Stock Exchange amounted to £80 million and £1,067 million respectively. Income tax was deducted by the companies before payment to the tune of £440 million. Mr. Wilson has no hope of getting Parliament to agree—in addition to the new corporation tax—to the imposition of an extra £440 million on individual share-owners. Nor, I am sure, would he seek to do so.

As for a tax on capital gains, I am on record in these columns and in my book The Split

Society as favouring a tax on capital increment rather than a capital gains tax, which always dis- runts and distorts the capital market. (Witness the effect on the New York Stock Exchange, where a shortage of stock prevails because few people are willing to pay the gains tax of 25 per cent.) With a small tax on capital increment there would be no need for a capital gains tax. I estimate that a 5 per cent tax on total capital increment each year would bring in about £200 million. That would probably be a limit beyond which Parliament would be most unlikely to go.

There are some people who try to make our flesh creep by suggesting that the Labour Gov- ernment is definitely out to soak the rich capitalist. Mr. Harold Wincott, for example, who was so keen to present the distinguished Cambridge economist, Dr. Nicholas Kaldor, as a Bolshevik that he confused, in his article in The Financial Times on October 13, the Radcliffe report of 1959 with the Taxation Commission report of 1955 to which Dr. Kaldor added a minority report recommending a capital gains tax. As the United States and other civilised countries have had a capital gains tax for a long time, Dr. Kaldor was merely being up-to- date and reasonable. Mr. Wincott should realise that a Labour government is not out to soak the rich, but to apply social justice. No govern- ment today could get the trade unions to agree to the vitally important incomes policy unless it showed them that social justice was being done by way of taxation of profit incomes and capital wealth. Everyone knows that tax-wise capital has been more leniently treated than wage income. I marvel that there is anyone in the City who is not 'left-wing' enough to recognise this elemen- tary point of practical politics. But, fortunately, Mr. Wincott does not represent the City, but only his own grumbling self, eternally fussing in his articles, because he thinks that capital gains on the Stock Exchange barely offset the deprecia- tion of money. There are some people who want to have their cake and eat a big slice of someone else's. I leave Mr. Wincott, the capitalist tortoise engaged in his race with the socialist hare (rising

prices), to the condemnation of those forward- looking people in the City who are anxious to see social reform come to the support of their capital market and its institutions.

Previous page

Previous page